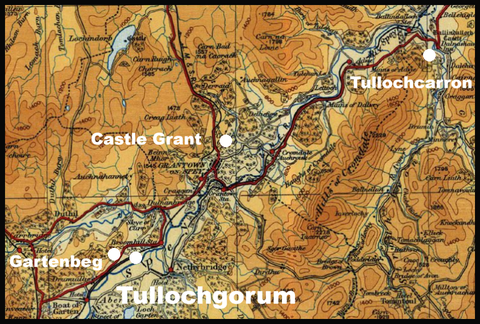

On the page about the Grants of Dalvey we established that Duncan, the progenitor of the family originally of Gartenbeg, which became the (second) Grants of Dalvey and Patrick, the progenitor of the Grants of Tullochgorm (variously Tullochgorum, Tullochcorme etc.) were both illegitimate sons of Chief Ian Roy Grant (killed in 1434). We should note that, by the locations of the original lands allocated to them, they started off as neighbours.

Base map: maps.nls.uk/

Parentage: Patrick’s mother was either the daughter or the wife of Baron Lamb of Tullochcarron in Stratha’an. Patrick was clearly named after Ian Roy’s father, so we might suppose that he was his firstborn – so it is possible that that he was born before 1410. If, on the other hand, we look at Fraser’s pedigree we find a later Patrick Grant giving land to his “future wife” in 1668. If we assume he was 21 at the time and if we apply the 25-year inter-generation gap then the first person on the pedigree (also a Patrick) would have been born about 1472 – which accords with his being recorded as a witness in 1530 (when he would be about 60). This would imply a birth for the progenitor Patrick c1422. There is not much wriggle room here, else the Patrick of 1530 would become unfeasibly old. The 1422 date is also rather more consistent with the dubiety as to whether it was the wife or the daughter who was the mother and if it is reasonably accurate then the matter of why Ian Roy would name two of his sons Duncan becomes even more pressing.

Given the intense strength of feeling between Ian Roy Grant and Bigla Beg, casual extramarital activity on Ian Roy’s part would seem unlikely, but would be far more readily understood if we suppose that she died at a relatively young age, perhaps even in childbirth.

Tullochgorm: Rather than pre-existing, it is suggested that the name Tullochgor(u)m is a pun on the name Tullochcarron; this finds some support in that the farm is not characterised by being on a notable “tulloch”. Indeed given the name Gartenbeg on the west bank of the Spey mirroring Gartenmore on the east bank and given that Tullochgorm was only one davoch in extent (giving rise to a later generation being mocked as a “bonnet laird”), it does rather suggest that a larger landholding was carved up to make this provision.

On and around the lands are a number of ancient monuments. There is a pair of standing stones (canmore.org.uk/event/664680) and what the map calls a “stone circle” but which actually appears to be a chambered cairn (canmore.org.uk/site/15443/tullochgorm) and not far away a large cairn (canmore.org.uk/site/15447/toum). As these second two are “prehistoric” my own guess is that the standing stones were set up as markers guiding people as to where to cross the Spey – and hence long predate the tribes which became the Picts.

Attitude: The Grants of Tullochgorm were very loyal lieutenants to their chiefs and seem to have been content to remain where they were, whereas the Dalvey family were on the move seeking to better themselves whether financially or socially, although the Tullochgorms did absorb some neighbouring land over time. However the small estate they had made it ever more pressing that younger sons find futures for themselves so for both reasons we find them taking every opportunity to marry heiresses – one such being what appear to be the mac Robbie Grants of Glenlochy and Inverlochy of upper Stratha’an.

Their loyalty was eventually became problematic at the time of the Jacobite rebellions.

In 1726, and despite being a wadsetter, Patrick Grant, the then chieftain was obliged to sign a bond by which he agreed to pay the chief £120 per year so long as the wadset was not redeemed. Fraser does not give any reason, but we may rather suppose that this may have been a recognition of some Jacobite sympathies and this was the mildest reparation (the chief had expended a lot of money raising a military force in the ’15 for which the government never compensated him).

Matters got worse in the ’45.

- George Grant, the then Chieftain was one of those who signed the Treaty of Neutrality (for which see Chris Grant’s book), from which we may infer some Jacobite sympathy;

- his brother Patrick who had gone to live in Glenmore (presumably above Loch Morlich) gave shelter to the Prince after Culloden;

- his paternal uncle Allan fought at Culloden for the prince

In 1751 he accepted an increased feu duty of £191 13s 4d yearly after which Sir Ludovick agreed to hold back on redeeming the wadset for 24 years We can readily see, then, the context in which the 1752 Tullochgorm Memoirs were written.

The wadset was redeemed in 1777 whereafter George became a tacksman only, dying still at Tullochgorm in 1787 aged 84. His son, Alexander, had, then, to find an income apart from the land which included being interned by the Spanish in 1780. He died in 1828 at the age of 97 and without issue, but in the meantime the lease of Tullochgorm had been taken up by his nephew, Patrick, who doubled as the minister at Duthil.

The minister Patrick’s daughter Anna married her third cousin (on the paternal line), Major John Grant; they rented Auchterblair (just SW of Carrbridge) and several of their descendants, who took up the name “of Tullochgorm” went on to stellar careers in the armed forces, including Field Marshall Sir Patrick Grant (1804 – 1895). Dr Isabel Frances Grant, founder of the Highland Folk Museum also belongs to this line.