Chapter 4b:

The Bissets in Scotland

|

Chapter 4b:

|

|

We have a period of a hundred years between c1140, the first definite recording of the name Bisset in Scotland at Upsettlington and c1240 the date immediately prior to the “Bisset Expulsion”, of which more later. Although we have a limited knowledge of the family who appear briefly and are recorded from time to time we do not have enough knowledge to attempt a genealogy in the same manner as we have tried for the Anglo-Norman Bissets. The Scoto-Norman Bissets only give us brief fragments of the whole, insufficient to stitch together an overall picture.

How and why the Bissets came to Upsettlington can only be guessed at but we can now be certain that this branch of the family was almost certainly in Scotland by or shortly after c1125 ignoring Scenario 5 for current lack of confirmation. They must have been invited into Scotland by King David (1124-1153); there is no hint of any evidence that they came from England. The first confirmed date we can be sure of for a permanent Bisset family arrival in England is 1153 in the shape of Manasser Bisset.

By the end of this hundred years of settlement they had not only gone forth and multiplied but prospered under the crown. We have seen that in a separate migration, William C had been recorded in Scotland first in 1150/64 and lastly in 1170 and in 1205 what property he held was regranted by the crown to another, so this migration apparently failed to survive in Scotland. We have also seen that an as yet undetermined Henry Bisset was recorded first in 1153 and finally in 1195. Whether this was one and the same Henry is not clear but we have not as yet found any reference to land holdings or family so it would seem that this potential branch also failed in Scotland. There is also the report of a Bisset or Bissets arriving in Scotland with King William the Lion in 1169 after Falaise, but once again we have no evidence as to who they might have been, if they held any land or indeed if they ever existed.

Bearing these facts in mind the catalyst for the growth of the family could only have come from Upsettlington And why not? This hundred year period would comfortably cover four generations which could easily have supplied enough young male Bissets in need of pastures new.

We know that one lot of Bissets settled in the county of Berwick, and another in the north of Scotland where they had land in Ross, Banff and Aberdeen. In Aberdeenshire they were to hold Aboyne and probably Lessendrum; Beaufort near Beauly was one of their seats in what was then Ross where in 1230, John Bisset founded a priory. He had also in 1226 founded a leper house in connection with the church of St Peter’s Rathven, in Banff; this was the first leper house in Scotland. On 19 June, 1226, John Bisset granted to the Church of St Peter’s and the house of lepers at Rathven, and the brethren serving these, the Church of Kiltarlity with its pertinents.

This was done for the soul of William, King of Scotland; so the grant referred to by King Alexander had probably been made to Bisset by King William the Lion. In 1222, Alexander by a charter dated at Fyuyn (Fyvie), 22 February and witnessed by Robert, his Chaplin, John Bisset, Walter Bisset and confirmed by William Comyn, Earl of Buchan, grants the monks of Arbroath, the church of Buthelny (now Meldrum). Between the years 1221-1236, A Walter Bisset founded the Preceptory of the Knights Templar at Culter on the Dee, and in 1237, Alexander II, granted the Knights a charter of liberty to acquire the land. The building included a chapel, and a Walter Bisset also gave to the Preceptory the church of Aboyne. We also know that in 1367 yet another Walter Bisset was still at Coulter holding half the Barony of Coulter. On 17th August 1233, Walter and William Bisset both witnessed at Strivelin a charter of King Alexander II, to the monks of May. (The Isle of May)

In the year 1240, according to the author of The Priory of Beauly the Bissets possessed the following estates: - Walter Bisset was Lord of Aboyne, and resided at Aboyne Castle. His nephew, Sir John Bisset, was Lord of the Aird; he first appears in the deeds of arrangement between him and Bricius, Bishop of Moray, who died in 1221, and which are confirmed by King Alexander in the same year; he resided either at Lovat or Beaufort, in the county of Ross.

Between 1179 and 1187, William the Lion was engaged in putting down the rebellion of Donald MacWilliam, who claimed to be the Celtic heir of Malcolm Canmore, this was a dynastic rebellion and it has been claimed that William took the opportunity to expel large numbers of Celtic people from Moray and Ross. I believe that there is confusion here between different risings in the north and in fact this statement comes from the Holyrood Chronicle 1163, “King Malcolm moved Moray men” A.A.M. Duncan (S-MK p191) believes this to more likely mean the removal of the See of Moray rather than the removal of the population. If people were removed it would more likely have been those of the ruling elite rather than the peasant population. Notwithstanding this point it would be reasonable to conclude that John Bisset’s acquisition of the Aird was either as a reward for service rendered in putting down Donald MacWilliam and or to put the King’s men in place on the ground so that William’s control was more effectively extended. It was in 1179 when King William and his brother took an army into Easter Ross and started the building of Redcastle on the Black Isle to protect the Beauly Firth and the hinterland of Beauly and Dunskeath Castle on the northern entrance to Cromarty Firth to further protect Moray from the north. This would have been a logical moment to put in place his own supporters among whom John Bisset must have been prominent.

Another nephew, William was patron of the church, and probably owner of the estate of Abertarff in the same county; Robert Bisset, cousin of Walters was Lord of Upsettlington, in the county of Berwick. [Now Borders]

A note from MacFarlane’s Genealogical Collections, Vol ii :- “one John Bisset, a great courtier with King William the Lyon matched Agnes the kings own daughter and was settled in Lovat with commission from the king. A man of great courage and activity, his second son John, succeeded him in the 20th year of his age and married one Jean Haliburton, daughter of the Baron of Culbrynie, Anno 1206.”

How did the Bissets appear in Aboyne? Here I am indebted to Beryl Platt who pointed out the potential significance of the Bisset arms of Lessendrum being an early differenced version of the arms of Mar. This fact would indicate a close relationship at some point between Mar and Bisset and a marriage between these two families. My colleague Adrian Grant in correspondence with Alex Forbes of Druminnor has thrown further light on this and put forward a scenario which without any conflicting evidence to the contra seems to supply an elegant solution.

We start with the so called Wardlaw MS written by the Rev James Fraser Minister of Wardlaw and which sets out primarily to tell the story of the Bissets and Frasers. (It can be found in MacFarlane’s Genealogical Collections [Vol.ii] it is a MS which does contain acknowledged errors and has generally been dismissed by historians for that reason.

As part of our story it makes a claim that a John Bisset of the Aird married “Agnes, daughter of King William the Lion.” A claim that has always be rebutted on the basis that all of the King’s offspring legitimate and natural were well known and did not include any of the names of Agnes.

But what if this statement were true? William the Lion was born in 1165 and came to the throne in 1143 aged 22. His early life would not necessarily have come under the microscope of the scribes until his enthronement and this period of 10 years of relative invisibility would have given him plenty of time to father a series of natural children unknown to the scribblers of the period. William of Newburgh wrote “For a long time he postponed the good gift of marriage either for offspring or for the relief on continence” Howden noted that after his wedding in 1186 “he lived most virtuously” yet this was a man who fathered thirteen known offspring!

There was plenty of time and opportunity for the young prince to sow a few wild royal oats out of the public gaze and not forgetting that until the death of Henry Earl of Northumberland in 1152, the second son of David I, William’s future position as King was not expected or imminent.

William's legitimate children were:-

1. Margaret. b. 1193, who married Hugh de Burgh.

2. Alexander b, 1198. (Later King Alexander II) who married (i) Joan, daughter

of King John of England, (ii) Mary, daughter of Enguerrand III, Lord of Courcy.

3. Isabella b.?, who married Roger Bigod, 4th earl of Norfolk

4. Marjorie b?, who married Gilbert Marshall, 4th earl of Pembroke.

Known illegitimate children.

5. Margaret, by a daughter of Adam of Hythus

6. Isabella, who married (i) Robert the Brus, (ii) to Robert de Ros.

7. Robert of London. b.?

8. Henry Galightly. b,?

9. Ada, who married Patrick 4th Earl of Dunbar.

10. Aufrica, who married William de Say.

11. Unnamed child.

12. Unnamed child.

13. Unnamed child.

The last three children could have died at birth hence no christening or forename or just simply not have been known to later scribes. There was plenty of scope for William to have fathered numerous illegitimate children of whom there is no surviving evidence or record.

Having demonstrated that there is no valid reason to rule out this statement in the Wardlaw MS, who was Agnes? Because the Bisset arms are the differenced early arms of Mar and that a Walter Bisset was Lord of Aboyne we must turn to the House of Mar to find Agnes.

Morgund 2nd Earl of Mar, born c1115 had a wife named Agnes, the estimated date of a marriage between John Bisset and Agnes would be c1180, so Agnes would have had to be born about 1160/5. The naming pattern with Agnes being named after her mother fits, as does the location, so how could this have happened?

At the appropriate time the young Prince William was Lord of Garioch ([pronounced Geary), a Thanage and as such belonging to the crown. The current thinking is that Garioch was hived off from the Earldom of Mar in the early 12c, becoming or even reverting to a thanage and therefore crown property.

Adrian Grant’s proposition is that the thanage of Garrioch was held at one time by the young William post 1054. The thinking behind this is that once William became heir presumptive he would have been encouraged to develop not only his martial skills but also those of estate and man management. What better place than Garioch, it would not only fulfil these needs but would also give a higher profile to the crown authority in what would still be seen as frontier territory. The Earldom of Mar was immediately adjacent to offer support if needed and there would have been plenty of opportunity for social intercourse between the two houses, something which William may well have taken to its logical conclusion.

William became heir apparent in 1153 with the death of Malcolm IV at the age of 11, which would have been the time that he would start to become involved and educated in the arts of kingship so it is well within the bounds of possibility that an 11/12 year old William could meet a 15 year old daughter of Morgund, Earl of Mar with natural results. The timing is right; the location is right and the opportunity there.

Further supporting evidence is that we know that David, younger brother of William, Earl of Huntingdon and all the other titles which went with being Scottish heir apparent, Earl of Northumberland, Earl of Carlisle, Earl of Dunbar and tellingly Earl of Garioch c1180. So it is entirely logical to assume that like the other titles William had held Garioch before David.

This takes us back to the Wardlaw statement that John Bisset (of the Aird) married Agnes (illegitimate) daughter of William the Lion.

This marriage produced we believe four children, we do not know exact dates or in which order but as Sir John Bisset inherited the important and hereditary estate of the Aird it seems safe to assume that he was the eldest son. Walter who married Ada of Galloway seems to have acquired the estates of Aboyne and Stratherrick from his mother who is at one point noted as Lord of Aboyne, probably before Walter was of age. This would be quite logical if Aboyne was either a thanage or royal holding and within the gift of his mother, a daughter of the King. Subsequent events show that it did indeed remain a royal estate when it reverted back to the crown with Walters’s later exile. It is debatable which was the more important holding and therefore inherited by the eldest son but as the Aird was not only an hereditary estate and not subject to the royal whim but was an existing estate I am assuming that it was considered the more important and greater estate.

A third son William held Abertarff again very probably via his mother and the daughter Mary married Gregory Grant and it was this marriage which would have brought Stratherrick to the Grants as dower.

Regardless of her ancestry Agnes and John Bisset went on to produce three boys, Walter of Aboyne – William of Abertarff – John of the Aird and a daughter Mary who married Gregory Grant. We would expect Agnes to be named after her mother’s mother who would have been Agnes wife of Morgund Earl of Mar and this would explain the Bisset Arms and the influences at work as to how Walter obtained Aboyne.

This is a very plausible scenario. We know the Bisset arms indicate a very strong link to Mar, we know that this would only have come about via marriage, we know that the Scottish naming system means that we should look for an Agnes as the maternal grandmother – we know that this fits with Agnes wife of Morgund – and we know that for any Bisset to have held Aboyne it would have needed the say so of Mar. What we cannot be absolutely certain of is was the father the young William the Lion, it seems a possibility but regardless of its authenticity there seems little doubt that it was the marriage of Agnes to John Bisset that was the catalyst for the Bisset expansion in the Highlands.

This story is further complicated by a conflicting version of events which has “Ada” as being the King’s sister. This is possible, William’s father was Henry, son of David I, Henry married Ada daughter of William de Warenne, 2nd Earl of Surrey. Henry had three legitimate children and four illegitimate ones of which one was an Ada but is recorded as marrying Malise, son of Ferteth, Earl of Strathern.

I think that we can conclude that John Bisset married “a close relative” of the King either an illegitimate daughter or a sister.

In 1245 by a Bull from Pope Innocent IV, the Priory of Beauly was erected for the Benedictine monks. King Alexander II confirmed to the monks the land of Strathalvay; the Monastery was erected in Insula de Ackinbady in Strathalvy at the site of the chapel of St Michael. John Bisset was entrusted with its erection and care. The Prior Pater Jawmo came with six monks to Lovat and renamed it Beauly.

Despite the inherent problems for a rising family in the 13th century, the Bissets were doing well; they held large swaths of land in the Moray Firth area, in Aberdeen and Abertarff. They were accepted at court by the King, witness to his charters and John of the Aird, married Agnes, a “close relative” of William I, and had acquired the lands of Lovat, in the Aird. But disaster was about to strike the family, an event called by historians “The Bisset Expulsion.” It is a rather over worked title as the “expulsion” only affected Walter Bisset of the Aboyne and his land and Sir John Bisset of the Aird, none of the other assorted Bissets in Scotland seem to have been immediately affected. What it did do was to stop any further expansion and break what political and territorial power the Bissets had at that time and which they were never to recover.

I have thought a lot about the events surrounding “the expulsion” and I now believe that this was not a straightforward case of murder but part of a much larger power play between the Comyns and the their rivals for power. This event needs to be put in context with the political scene at the time and I shall try to unravel the story. Any rise to power and visible presence near the centre of power and decision making causes jealousy and resentment by those who believe they are being displaced and is only achieved at a cost, friends, deals, political manoeuvring and double dealing, nothing much has changed since the 13th Century!

“In the late summer of 1211 the king appointed a powerful team consisting of the earls of Atholl (Thomas of Galloway) and Buchan (William Comyn) Thomas the Durward and Malcolm son of earl Morgund (Morgan) of Mar.(who can now be seen as a potential father in law of king William. pg.) Ultimately this team, supported by Saer de Quinci earl of Winchester and a force of mercenaries from Brabant succeeded in suppressing the MacWilliam revolt but not before the earl of Fife had resigned or been removed from the wardship in 1212 and been replaced by earl William Comyn”. (B&S)

“It seems to have been in the aftermath of this military success – but by no means immediately – that the leading figures or their kindred and dependents, were rewarded with infeftments and office in Moray. In 1226 Thomas the Durward appears as sheriff of Inverness, while another record of the same year shows James son of Morgund– Malcolm’s brother- holding the feudum or fife of Abernethy. About the same time, Gilbert the Durward appears as lord of Boleskine on the eastern shore of Loch Ness. In this period too, Thomas the Durwards son Alan makes one of his early appearances on record, as lord of Urquhart on the loch’s western shore, while Thomas of Thirlestane, a vassal of earl Thomas of Atholl’s brother Alan lord of Galloway, acquired the lands of Abertarff by the head of the loch.”. (B&S)

As can be clearly seen after the successful suppression of the macWilliam revolt in Moray, (1211-13) all the main participants on the winning side (and by definition their families) under the leadership of William Comyn, the Justiciar, were rewarded with offices or land in Moray. But just below the surface were two rival factions striving for political control, the Comyn faction which included the Earl of Atholl and opposed by Thomas the Durward.

The Comyn an Anglo-Norman family (but of Flemish origin) had first come north with King David I (1124-1153) when as Earl of Huntingdon he succeeded to the throne of Scotland. William Comyn became his chancellor and it was his nephew another William who married Marjory daughter of Fergus the last Celtic earl of Buchan “other members of the Comyn family held lands in Badenoch and Kilbride and were for a time earls of Menteith and Angus and one was bishop of Brechin. The king appears to have treated the two earldoms [Buchan and Mar] differently leaving the Comyn’s as earls of Buchan where they remained in un-disputed possession until the time of Robert the Bruce. On the other hand the Earldom of Mar was reduced by the creation of several lordships not responsible to the earl, notably the Garrioch based on Inverurie, Strathbogie (the name eventually being changed to Huntly), the Bisset lordship of Aboyne and the lordship based on Lumphanan for the Durwards. The aim seems to have been to allow the king better control of the gateway to the rich and troublesome province of Moray…….. By 1220 Walter Bisset possessed a lordship based on Aboyne and was a neighbour of the Durwards”. (C of C)

“The Durwards may also have been of Anglo-Norman origin but all we know is that they were settled in the 12th C at Lundie, north west of Dundee. Malcolm de Lundie married the daughter of Gilchrist, earl of Mar. Through his son Thomas claimed the earldom; it eventually went to a descendant of earl Morgund, a former earl and Thomas a lordship stretching from Cromar to the bridge of Canny and northward to Alford. Malcolm was appointed the king’s doorward and the family name became Durward. (C of C)

So we can see that while the Comyn were the most powerful force in the area, the combined families of Durward and Bisset would be seen as a threat to their power base and there is plenty of evidence to show that the Bissets and Durwards were close to each other.

Alan Durward married Marjorie the illegitimate daughter of King Alexander II; he also became guardian to the heir to the throne of Alexander (III). “about 1254, however there was a crisis and he lost control apparently due to an attempt on his part to legitimise his wife and thus allow his heirs to claim succession to the throne if Alexander iii should die childless. He was however unsuccessful in his petition to the Pope, the Comyn’s seized the person of the king and Alan went to Gascony and Castille were he joined Prince Edward of England (the future Edward i) and served with him in place of the earl of Strathern who owed service for his English possessions. After returning to Scotland where he again served a more mature Alexander iii, he joined Prince Edward in 1268 and accompanied him on crusade to Palestine. (C of C)

At the period prior to the expulsion we have two power blocks - on the one hand the faction headed by the Comyn and on the other the faction consisting of the Durwards and the Bissets with the King trying to hold the balance. It seems clear from the events which unfold that the King was not in full control and afraid of the Comyn power. He had married his daughter to Alan Durward and given him custody of his heir so regardless of whether this was done as an act of friendship or political expediency he did seem to favour the Durward/ Bisset faction.

Thomas Durward was Sheriff of Inverness; the office of sheriff was established in Scotland by King David I. He took the concept from the court of his brother-in-law, Henry I. of England. I have been unable to establish a date for the creation of the sheriff at Inverness, the traditional Grant texts claim very early incumbents but Thomas the Durward, is the earliest recorded Sheriff of Inverness (1226) (Moray Reg., no 72; cf.ibid, no.71) Laurence le Grant was the third recorded in 1263 or 1264 (Exch. R., i, 13) The claim by the author of The History of the Priory of Beauly, that Gregory le Grant was sheriff in 1263, is disputed by Fraser, who has this as a misreading of the relevant text and it should be Laurence not Gregory. This does not preclude Gregory from having been sheriff at a previous date it just means that there are no written records yet found to prove this)

In addition to the sheriffdom, Gilbert Durward became Lord of Boleskine and Alan Durward, son of Thomas, Lord of Urquhart. The Durwards wanted an earldom to match the Comyns (Earl of Buchan) and to further break into the forefront of the Scottish aristocracy; these were two Anglo-Norman families fighting for supremacy. Thomas Durward had been thwarted in his claim for the earldom of Mar, when it had come under the influence of the Comyn, when William, Earl of Mar, an alternative line, married William Comyn’s daughter. Another source of friction was related to the earldom of Atholl. For a short period 1233-37, Alan Durward had held the title after Thomas Atholl, quite how is not clear; it may have been via a wardship of the heiress or marriage to Forveleth the heiress. As with Mar this earldom was to come under the control of the Comyn through their relative Patrick of Atholl, son of Isabel and Thomas of Galloway.

Both these two factions had of course their supporting families, those that were feudally bound to them, close neighbours presenting a united front out of fear, opportunists and outright opponents to the other side - enter the Bissets.

They were another expanding family with royal connections, approved of at court, controlling expanding estates. It is a fact however that when you expand your property you move into or compete with your neighbour for that ground; and in the case of the Bissets the main competing family was the Comyn and this inevitably led to friction which made the Durwards and Bissets natural allies. The Bissets were in no way hanging on to the Durwards coat tails, they were quite capable of making waves on their own account. So the stage was set for a clash in which only one side could win.

All the simmering tensions between these three competing families were to explode at Haddington in 1242 with the death of Patrick, heir to the earldom of Atholl.

The following events were well reported by the scribblers of the day, Matthew Paris, the Melrose Chronicle, and the Lanercost Chronicle; they all had their own spin but reached broad agreement of the main story.

A jousting tournament was held at Haddington, about half way between Edinburgh and Dunbar and in one of the jousts Walter Bisset of Aboyne, was matched with Patrick, Earl of Atholl, each knowingly or not representing the two competing factions. Patrick Earl of Atholl was the son of Thomas, the younger brother of Alan the Constable. He, Patrick had acquired the earldom with Isabella, the heiress. The relationship was further entwined as Alan of Galloway had married his sister to Walter Bisset of Aboyne. Alan had died in 1234, leaving three heiresses, we know nothing of what happened to Thomas’s lands in Galloway or Ulster, lands which would in the normal course of events passed to his son Patrick, when he came of age. By marriage Walter Bisset became an uncle to Patrick of Atholl.

Uncle and nephew, by marriage meet in a jousting match; Walter is unseated, not perhaps unsurprisingly by his younger nephew. During the night following the joust the lodgings of Patrick of Atholl were burnt down it was said in some reports that the fire was used to conceal a previous murder and that wood had been heaped up on every side to prevent escape. Patrick and his two attendants died, the Bissets being immediately suspected of foul play. Patrick was said to have been warned of the danger to his life by the wife of his enemy. If as was purported the culprit was Walter Bisset, it would have been his wife, Patrick’s aunt who gave the warning, a warning that does not seem to have been heeded, if in fact ever given.

Had this death not involved representatives of the two opposing power factions within the Scottish court it would probably been a nine day wonder. But in this case, far from it, it was to destabilise the power structure in Scotland and lead to a threatened invasion by England.

This death posed several questions:-

A) Was it a revenge attack for losing the joust as was suggested by some?

B) Was the fire a genuine accident which was quickly taken up and used by the

Comyn faction to denounce and destroy the Bissets?

C) Was this a pre-planned conspiracy by Walter Bisset to murder Patrick and

was the real reason related to the inheritance of Thomas of Galloway’s

estate.

D) Was there a “warning”?

There was no clear answer then nor is there now, with the then equivalent of the popular press all putting forward their own theories and being supporters of one or other of the parties involved it is impossible to decide on the truth with any great certainty.

In answer to A), even by the standards of the age, murdering one’s jousting opponent because of being knocked off one’s horse seems very drastic action to contemplate, particularly if the victim is related by blood to your wife. After all the whole point of a joust was to unseat your opponent and Walter who must have been a seasoned campaigner was unlikely to have lost his temper to the extent of organising a murder, On the whole I think it an unlikely scenario. Walter’s subsequent conduct shows he was no fool and he must have realised the potential capital his enemies would make out of this situation.

B), This is potentially the most likely scenario, the story of the wood piled up and warnings from the wife of his enemy may be true but they are the sort of stories that become urban myth and always emanate from such a situation and become seen as “facts” and there is always someone to put a spin on the event. We all know “that he who takes the minutes controls the meeting”. If wood were piled up why didn’t anybody do anything about it? Who were the men supposedly seen doing this? Who saw them? Could they just as easily have been Comyn supporters? Why should they be Bisset retainers, Walter had left Haddington before the event and was clearly not returning, no source mentions John Bisset ever being at Haddington so why would Bisset retainers be there? Why was the secret warning not heeded or at least extra precautions taken to protect Patrick?

The salient facts seem to be that the house that the Earl of Atholl was in did burn to the ground and his body was found afterwards. The house could have caught fire for any number of reasons, a spilt lamp, a drinking party or deliberate arson. It beggars belief that people stood and watched timber being put around the house by arsonists and did nothing about it. The subsequent stories concerning this seem far fetched. Clearly there was no form of autopsy so we have no proof whatsoever that the Earl death was anything other than asphyxiation.

While there is every possibility that the events given by the chroniclers of the day were correct it seems much more likely in view of the power struggle that that going on that this was a desperate and high risk ploy by the Comyn. They could have murdered the Earl or simply just taken advantage of his accidental death in a fire to mount a swift and savage attack on the Bissets. Because regardless of what actually happened the Comyn moved very swiftly, too swiftly perhaps for them not to have had pre-knowledge of the situation.

C), It could have been pre-planned, but and a big but, it would have to have been carried out in a very public place and a very public way of achieving Patrick’s death, Walter must have known the consequences of such an action; it would in my opinion been too high a risk to contemplate.

With regard to D) if there had been a warning nobody seems to have taken it seriously and it seems much more likely that Ada, Walter’s wife was “reminded” after the event where her family loyalties lay.

Regardless of what the true facts were, the Earl of Dunbar, the King’s younger brother and friends of Patrick were straight off the mark in implicating Walter Bisset and accusing him of instigating with John, his nephew, the supposed murder. They had their tails up and were determined to use this as a means of removing the Bissets from the kingdom.

Walter Bisset protested his innocence and even the Queen was able to give him an alibi stating that Walter had been in attendance to her at Forfar on the night in question. How good an alibi this was is somewhat suspect as when Walter lost his bout at Haddington he would have had to have extracted himself from the tournament and either ridden from Haddington to Edinburgh, on to Queensferry, across the Forth, ride right across Fife, across the Tay at Dundee and then on to Forfar; or from Haddington to North Berwick across the Forth to Earlsferry and then again across Fife, the Tay and to Forfar. Both would have been a hard ride particularly after having been unhorsed in a joust and the crossing from North Berwick to Earlsferry would have been dependent on the tide, state of the sea and a good ferry connection. It would have been possible but I think only just and the events that night at Haddington could make this alibi just as incriminating as helpful.

We are told that the royal party had actually been staying at Aboyne, Walter’s home and that the Queen was following Alexander, the King south, attended by Walter Bisset who was to be implicated in the murder, and accused of organising it.

Walter had his chaplain excommunicate all who had been implicated in the murder, asking the Bishop of Aberdeen to publish this sentence throughout the diocese. As we only know of Walter and John as being directly accused of the crime who else this was aimed at is somewhat of mystery. All we are told is that Walter’s involvement was seen by the inhabitants of Haddington as a direct result of his retainers having been seen during the night of the fire. As we know Walter was not there, unless we disbelieve the Queen, we must assume that “seen” was more in the nature of seen to be his handiwork rather than physical presence. Retainers of all the knights at Haddington must have been moving about on that night so unless there was evidence that Bisset retainers were seen actually in an incriminating situation the statement is meaningless.

None of this was to stop John Comyn and Alexander, heir of Buchan, and his uncle the Earl of Monteith from attacking the Bisset lands right up to Aboyne castle. While this may have been an over reaction by the younger Comyn it clearly annoyed Alexander, the King as he had already appointed a day for the hearing and trial of Walter Bisset, at Forfar.

The king despatched his own guard to forbid the Comyn in their lawless actions and charged the authorities of Mar for the safe conduct of Walter to Forfar. Walter offered to prove his innocence by wager of battle, by which was trial by combat. He refused to accept the judgement of his peers, assuming probably correctly that as the majority belonged to the Comyn faction he would never get a fair hearing so he put himself at the mercy of the King. The King clearly in danger of losing control of the situation postponed any decision until a meeting of the great “Moot” in Edinburgh. This conflict was in danger of destabilising the country and holding the trial at a later date when tempers had cooled and in front of a broader based gathering was a sensible decision.

The assembly decided to banish both Walter and John Bisset from Scotland and to forfeit their lands and possessions; they had to swear on Holy relics that on banishment they would devote the rest of their lives fighting the “infidel”. Needless to say this was an oath that nobody took seriously as there is no record that any Bisset went within miles of any infidel. This was probably the best deal that the Bissets could expect and they did get away with their lives. As I can find no record that actually implicates them in murder I think that a verdict of unproven is justified and the decision to expel them was more for the stability of the realm than anything else.

The report that the Bissets forfeited all their land is not wholly accurate. Walter Bisset had clearly been accused of the crime from the start but by the time of the Moot the accused had been expanded to include his nephew John Bisset of Lovat, (the Aird) he had been forced to flee with a price on his head. The King ordered his arrest possibly as much for his own safety so that he could be tried with Walter before the Privy Council. He was detained by George Dempster of Moorhouse at Achterloss and brought to Edinburgh and while he faced banishment, he did not however forfeit his estates as he had prudently already made them over to his son John, “the younger”. John was acting as Lord of Aird in 1258, some sixteen years after the affair at Haddington so he clearly still held the estates.

John and Walter went first to Ireland and in 1242, met Henry III King of England in Wales. John Bisset had met Sir James de Saville who was in Henry’s service who persuaded him to serve Henry in his war in Guienne, in return for a knight’s fee in Ireland.[Patents and Charters 27 Hen iii (1243) p 739] December saw him in Bordeaux confirming this arrangement (Pat and Chart., 27 Henry iii., p, 739). This fee included the Island of Rathlin off the coast of Antrim.

While in Bordeaux waiting on the King, his wife Margaret died, so John Bisset the senior late of Aird, now in King Henry’s service must have seen this as a clear break and the start of a new life. While Sir John Bisset had been in Ireland it was recorded by Bower (continuation of Fordun, b, ix., c, 62) that Allan, bastard son of Thomas of Galloway, and a natural half brother of Patrick the dead Earl of Atholl, had landed in Ireland and burnt a house of Sir John Bisset, he also obtained from King Henry a pardon in 1252 for having killed a follower of Sir John Bisset in Ireland. (Patent Rolls, 36 Hen iii., m, 12.) So the feud had still continued and some at least were convinced as to the Bisset guilt which may be why Sir John Bisset found service in Guienne attractive.

Dealing briefly with the Bissets of Aird before they leave our story; Sir John Bisset senior founder of the Priory of Beauly was as shown, banished from Scotland but not before settling all his estates on his son, John the younger, who as shown was acting as Lord of Lovat in 1258 and was no longer referred to as the younger as he was in 1242. He held his property by descent and not as his father appears to have done at one point by grant from the crown. John senior is reported to have died in Ireland, leaving his second wife Agatha, a widow and through her had a second family who formed the clan Eoin or Bissets of the Glens of Antrim.

John the younger died in 1259, and had before his death given dower to the Lady Agatha, his stepmother, so contact between the son in Scotland and his father in Antrim was maintained. He seems to also have had a son also called John, who died without issue, leaving three surviving daughters his co-heiresses, Cecilia who married William de Fenton; Elizabeth, wife of Andrew de Bosco; and Muriel wife of David de Graham.

If Forsyth’s account (Forsyth’s Moray, p, 20) is correct, the third John Bisset was witness to the writ which was a grant to Robert le Grant about 1268 from John Pratt, knight. If Charmers is correct (Caledonia, vol, i, p, 596) that Gregory le Grant married Mary, daughter of Bisset of Lovat, she must have been the daughter of Sir John Bisset the founder of Beauly. The Grants appear about 1345 to be in possession of Stratherrick, when they succeeded the Bissets and it is probable that they obtained the lands in marriage with a Bisset. The Bissets of Lovat and the Aird now disappear from our story, with the estate inherited by the three heiresses this particular line of the Bisset family ceased and we can return to Walter Bisset late of Aboyne, who we left in Wales meeting Henry III.

In December 1243 he obtained a grant from Henry III of the manor of Lowdham, for himself and his heirs, until he, Walter or his heirs should recover their estates in Scotland. [Charters 31 Hen iii, m, 13] Lowdham was directly adjacent to the manor of East Bridgeford, which was held by the English Bissets and nothing should be read into this without further evidence other than a coincidence. The King would have granted him any available manor which was within his gift. Past historians, Sir William Fraser and Edmond Batten believed that East Bridgeford and the manor of Allington in Lincolnshire were held at this time by a William le Grant through his wife Albreda, (a Bisset (28) ) this can now be shown as incorrect. He did hold these manors through his wife but much later as he did not marry her until 1274, 26 years after Fraser and Batten had him or his heirs in Scotland with Walter. The object of this grant was to keep Walter in Henry’s service as long as the King pleased. There is no record of Ada his wife ever going into exile with him or Walter making use of this manor as a base, the records show that he was much to busy on Henry III affairs to have ever spent much time there.

Perhaps more interesting is that I have recently found that Walter had at the same time, the manor of Ovington from the Lords of Bedale in Northumberland. Ovington is approx 96 miles south of Upsettlington. Why or how he acquired this manor is at the moment not known but it does pose two intriguing possibilities firstly that this was a holding going back many years and links Walter closely with the Bissets of Upsettlington which is what I believe to be correct and secondly he never had need for an English refuge from Henry III; he already had one, unless he thought the proximity to Scotland was to risky. Nothing in Walter’s subsequent actions and character to date make that seem likely. Henry’s gift of Lowdham was more I believe a political gesture to King Alexander than anything else.

When Walter met Henry III the legal argument which he used was “the king of Scotland had disinherited him unjustly and that since the king of Scotland was the liegeman of the lord king of England he could not disinherit or irrevocably exile from his own land one so noble especially unconvicted without the king of England’s assent.” This was an argument which would have been sympathetically received by any English king who all harboured the belief that regardless of anything else this was the position vis-à-vis the two thrones. The Treaty of Falaise had been quit-claimed at Canterbury in Dec 1189 by treaty between King Alexander II of Scotland and King Henry III of England so Walter’s statement was not strictly correct but it probably did him no harm in his appeal.

The name Walter Bisset was not unknown to Henry III. In 1224/26 a gift had been made to a Walter Bisset from the English Treasury and in November 1233 and a fragment has been found in Hereford which seems to be a command from Henry III to the justices to respite a plea in which a Walter Bisset who is with the king is party to “Hunalderwurde” [C of D. p, 220. item 1200.] What exactly this was about is not clear but the point is that a Walter and the King had previously met and done business in England. This may be our Walter or even his father.

It is easy from a modern perspective for Scots to see Walter as a traitor to Scotland but this is to fail to understand the whole gamut of feudal dues and duty. Kings of England generally saw themselves as feudally the liege lord of the King of Scotland and by the same token Walter. Whatever land Walter held in England and at this time we only know of Ovington he would have almost certainly been liable to be summonsed to serve the King of England as and when required. The King of Scotland and peers who held English estates were summoned to fight for Henry III in his various summer campaigns in France. This split feudal loyalty did cause confusion and strain from time to time but the general situation was that the Scottish kings only had feudal due to the English throne for their English lands and not for Scotland as a nation – the same rule applied to the barons they had feudal due to the lord be it king or superior lord for land they held in each country.

However Henry was much more interested in what Walter was able to tell him about the state of affairs in Scotland and its military capability and plans. Walter Comyn and family were seen by Henry as a destabilising threat on his northern border and fast becoming out of control. Walter Comyn had been accused by English chroniclers of fortifying castles in Galloway and Lothian. Henry saw Walter Bisset’s argument as if at not least persuasive, at least an excuse (added to the fortifying of the castles) to interfere into Scottish affairs. Another complaint that Henry had with Scotland was that under the Treaty of Falaise [by now quit-claimed] both countries were obligated to return to the other any person who was answerable to the crown of his own country for whatever offence. Scotland had been harbouring William de Mariscis and his son wanted by the English crown and this was in defiance of the treaty. Henry would have been “annoyed” at the very least as in 1237 he and Alexander had meet and agreed a further Treaty at York [see appendix v] which was clearly expected to resolve relationships between the two rulers and yet here they were only seven years later drawn up in opposing armies.

After the Treaty of York in 1237 Henry III cut back expenditure and possible expansion on his castles at Bamborough and Newcastle-on-Tyne and Hugh de Bolebec is commanded to spend as little as he can on the maintenance of these castles.

Henry, in 1244, on his return from France marched north accompanied by Walter Bisset, they reached Newcastle but nothing seems to have happened. Peace was made and confirmed at Ponteland and it was as a witness to this that John Bisset the Younger signed. On the English side we have Walter Bisset aiding the English king and on the Scottish side John Bisset of Lovat his relative and son of an exiled father in attendance of the King of Scotland. A contributing factor to this conflict was not the Bisett – Atholl dispute but the Scots giving aid to Henry III enemies in Ireland and it comes as no surprise to find that “at this time earl Walter Comyn and earl Patrick had to make an oath that they had not counselled or aided any of those men sent to attack or damage the land of the king (Henry iii) in Ireland or elsewhere to the displeasure (in odium) or dishonour of the king or that they had ever harboured any of the king’s enemies, particularly William de Mariscis and his son”

Without repeating the data given in Appendix III, The Bisset Timeline relating to the Bisset family we can readily see that from 1243 when Walter enters Henry III’s service there are at least eleven records in the Calendar of Documents which involve instructions to supply Walter with money “to sustain himself in the king’s service”. He is titled “Messenger”. What this job title actually meant is difficult to determine. It could have meant just that or more. He was clearly involved as a servant of the English crown in some sort of military capacity operating between Antrim and the West Cost of Scotland.

While no official state of war seems to have existed, Ireland was an English colony never far from unrest, the stock on the opposing shores of Antrim and the Western Isles shared many common blood lines and had an infinite ability to cause the English mischief. Walters’s job may have been part of a general “peace keeping” strategy.

According to A.A.M.Duncan, “Henry iii was not above meddling in Scottish affairs for, in the spring of 1248, he had allowed Walter Bisset to buy stores in Ireland for Dunaverty Castle on the Mull of Kintyre (opposite the Bisset Island, Rathlin) which he had seized and was fortifying.” Sometime during 1248 Dunaverty Castle was stormed by Alan ‘son of the earl’, illegitimate son of Thomas of Galloway, and evidently Walter Bisset was taken captive there, for on 13 January 1249 he reappeared in Scotland for the first time as witness to a royal charter.

It would seem likely that he owed his restoration to royal favour for the information he could disclose about the western seaboard. Alexander II moved in great anger that summer against Ewen of Argyle, who was expelled and restored in 1255 only at the instigation of Henry III - the only ‘Scot’ for whom he interceded. These facts suggest that the turncoat Bisset was able to disclose negotiations between the English King and Ewen and possibly other lords of the Isles.” Finally, Walter Comyn, Earl of Menteith, is not found as a witness to royal charters from the beginning of 1248, and other Comyns are exceptionally rare, while their ally Patrick, Earl of Dunbar, went crusading in the summer of 1248 and died. There can be little doubt that, perhaps with the aid of Walter Bisset’s disclosures, Alan Durward eclipsed the Comyn in the counsels of the King during 1248 and 1249.

There are potential political undertones here. Was Walter actually captured at Dunaverty or was this a put up job? Maybe feelers had been put out to Walter that encouraged him to become involved in a subterfuge. Was his capture by Alan of Galloway who while a bastard son could still be seen as a relative by marriage of Walters a coincidence or part of a conspiracy? Apart from Walter the main beneficiary seems to have been Alan Durward, Walters’s old neighbour and ally who gained favour at court with the information regarding English intentions which Walter was able to divulge, at the direct expense of the Comyn. Had Walter become tired of the conflict and absence of his family, was he in ill health? We shall never know but I find the means of his return to Scotland just a bit too neat.

For those who see history as one continuous conspiracy, the death of Patrick

of Atholl is fertile ground indeed, was it a premeditated plot by the Bissets?

To what extent was the crown involved? Did the Comyns play an even deeper game

in order to implicate the Bissets? Or if you see history as series of uncontrolled

disjointed events was this just a domestic fire which killed Patrick, but his

friends were so consumed with hatred for the Bissets that they were unable to

see this but allowed darker forces to manipulate this into a major political

event?

It seems certain that Patrick of Atholl was burned to death, the circumstantial evidence points to possible murder but the worth that can be placed in the “witnesses” has to be taken with caution. Murder or not, the death was used to try to destabilize and discredit the Bisset family by accusing them rightly or wrongly for the death.

No compelling reason has been give why the Bissets should be behind this. Duncan believes that it may well have to do with the Galloway inheritance; if there were a feud it would stand a good chance of being related to land. The Comyn and Bisset lands must have been fairly adjacent in north Badenoch; both holding territory at the edge of effective royal authority probably in a draconian manner and in pushing the extent of their own personal authority, clashed badly. It would appear that the King had reservations as to the guilt and had to take measures to stop the Comyns taking the law into their own hands. The fact that Walter Bisset reappears in Scotland in a relatively short time later and is witness to royal charters seems to indicate to me that this event was not quite as straightforward as at first appears. And significantly if Walter Bisset’s statement to Henry III is correct, they were never convicted of murder by the Privy Council.

Not withstanding their forfeiture and though they never again attained the influence they formerly had with the Scottish kings, the Bissets still remained a family of considerable influence and importance.

Walter never recovered his estates at Aboyne these had been taken back by the crown and may have been used by Durward for a short period but subsequent events indicate that he did retain the small estate at Lessendrum which remained a Bisset holding until very recent times. Walter has been noted as witness to royal charters in 1248 for King Alexander II and again in 1251 for King Alexander III, so he was not a prisoner, he was not persona non grata, he was accepted at court by the King and considered good enough to witness royal charters.

He died on the Isle of Arran in 1251, we must assume naturally as there is no hint of any other cause, he would have lost the manor of Lowdham at the time of his capture and turning in favour of Scotland. In 1252 there is a record of his IPM concerning his manor at Ulvington in Northumberland. This shows that “in 1253, before his death… far away in Scotland. He sent a messenger to Gerard de Bowes, This date is incorrect as Walter died in 1251] his bailiff of Ovington, with letters patent directing that Thomas Bisset his nephew should put in seisen of his manor of Ovington. Gerard was away and the messenger waited, but on Gerard’s return in a fortnight he refused seisin to anyone but Thomas in person, so Thomas Bisset came to Ovington and lodged there and demanded seisin. Then two free men one villain and the reeve of the town being at once called together, Gerard gave him seisin, saving the right of everyone.” [York’s Inq., (York’s Arch Soc.,) i.26 ] the statement in the VCH goes on to say that Sir Walters estates were forfeited for the murder of the Earl of Atholl and Ovington was seized by the King’s escheators.

What seems to have happened is that Walter knowing he was dying and would inevitably lose the Ovington estate when the English crown discovered it, sent his heir Thomas hot foot to salvage what he could. It was his Scottish estates that were forfeited by the Scottish crown not his English estates; they would however have been forfeited by the English crown once they became aware of them.

Walters’s death marked the end of the Scottish Bissets period of influence and power in Scotland, the remaining large estate of the Aird (Beauly) would soon be lost due to lack of male heirs. What happened to the estates at Abertarff is not clear but if Abertarff was not forfeit at the time of the exile it probably soon went the same way. Upsettlington remained a Bisset holding until the late 14thC, an overall period of some 230 years. There was still a Walter Bisset of Clerkington and Culter recorded in 1368 when he gave up lands in Fife.

Bissets remained in Scotland and some clearly prospered but were never to regain their former power. In 1296 King Edward I, of England marched as far north as Elgin, collecting the Stone of Destiny, many Scottish records and St Margaret’s portion of the True Cross; he made the Scottish Establishment sign an oath of fealty to him. He collected over 2,000 seals and signatures on what has been called “The Ragman’s Roll”. The following are the Bisset names that have survived on this roll.

Bifet, (Byfet) Wautier (del counte de Aberdeen).

Bifet, Waultier (del counte de Edeneburgh).

Bifet, Dominus Willielmus (miles); William. Bifet, chiualer).

Bifet, William (del counte de Edeneburgh).

The first Ragman Rolls were returns made in 1275 by commissioners appointed by Edward I, to enquire into abuses and usurpations made during his absence abroad on Crusade. The name derives I believe from a medieval game in which stanzas were copied onto a roll with a string attached to each. Each player would draw a string to apply to him or her and presumably the similarity of appearance led to the nick name being applied to the state document.

Despite the “expulsion” we can see that the seals or signatures of several Bissets were attached to the Ragman’s Roll of 1296 just 54 years after Walters’s exile members of the Bisset family still survived in Scotland in positions of note and prestige.

To summarise: the family of Bisset came to Britain from the continent in two clearly separate streams, firstly to Scotland at Upsettlington sometime around c1140. A minor second stream entered Scotland in the shape of William the Carpenter Bisset and the unknown Henry Bisset (possibly William’s brother)

This migration failed to take root in Scotland but William the Carpenter’s family did survive for sometime in England. The second main migration was into England spearheaded by Manasser Bisset in his role as steward to Henry II of England. We know that Manasser’s father had for a while holdings in Derbyshire but they seem not to have survived his life and Manasser seems to be the first Bisset who put down serious roots in England.

It is not clear where the family first originated from but they first made their mark due to Flemish connections with the House of Aumale and later in Norman service to Henry Duke of Normandy later Henry II of England.

It is very easy to write them off as Norman where without question they held land and one part of the family at least made their name and came within the Norman orbit but their roots may well turn out to pre-date the days of Norman expansion. Dr Melissa Pollock argues that the Scottish Bissets came from Aumale where they had become recent settlers from Upper Normandy. Further research carried out using continental sources may throw more light on this area.

In England they survived (just) for seven generations before failing, but all off the back of the good fortune of the first generation. They survived but added nothing further to land or status before failing due to lack of male heirs.

In Scotland they reached higher peaks of power for a time but lost this with the exile of Walter and Sir John Bisset. The family Bisset however continued but with decreasing land and influence until eventually Lessendrum, Aberdeenshire becoming only surviving property which they held until the middle of the 20th C.

In this paper we have only been concerned with the more prominent medieval Bissets but we have only to look at for example the Aberdeen phone directory to see that the name has more than survived in Scotland and of course world wide outwith Scotland.

In the period 1140 to 1259 [the death of John Bisset the younger of the Aird] one of 119 years there should using a standard 25 years per generation be a minimum of around 5 generations of Bissets plus spouses, probably many more. These generations will repeat with each new branch of the family. As we are only able to identify around 12 those names from surviving charters the chances of producing a reliable genealogy are small and speculative as often the mere mention of a name is insufficient data to accurately place that name in its correct place.

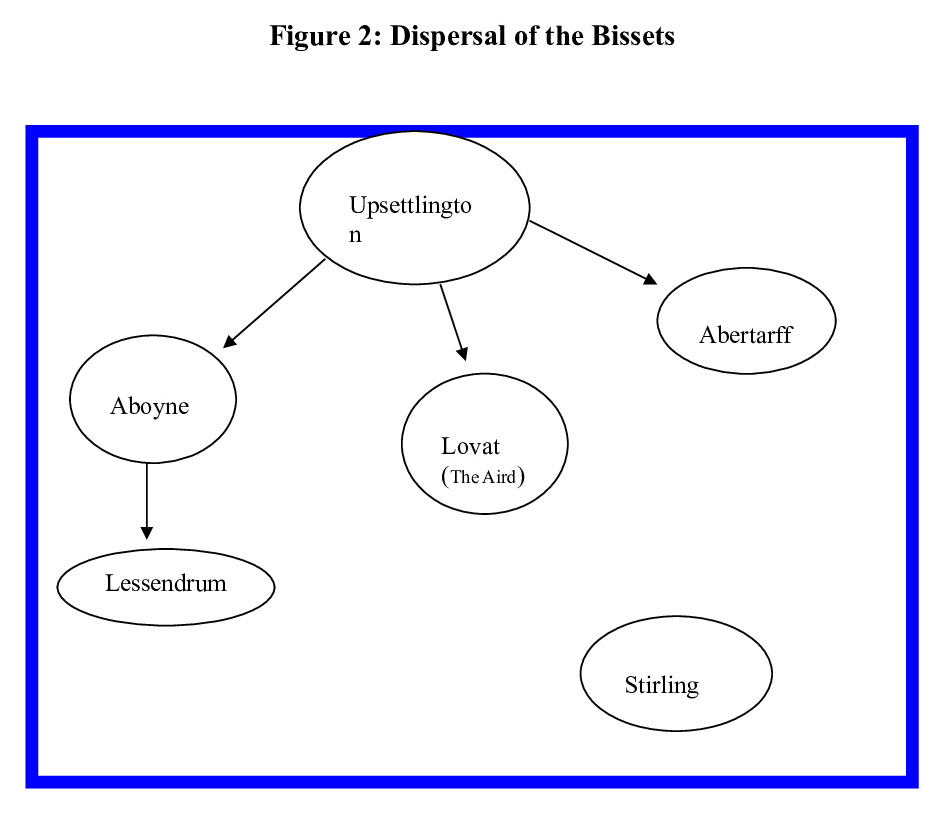

We know that within that time frame the Bissets held Aboyne, Lessendrum (which may have been originally part of the Aboyne holding) Upsettlington, Abertarff, and we are also told that they had appeared in Stirling by 1200. It is my current belief based on our knowledge so far that all these holdings stem from the original holding and personnel at Upsettlington. Fig 2 is a rough schematic of how I see the overall dispersal.

Download as figure_2.doc or figure_2.pdf.

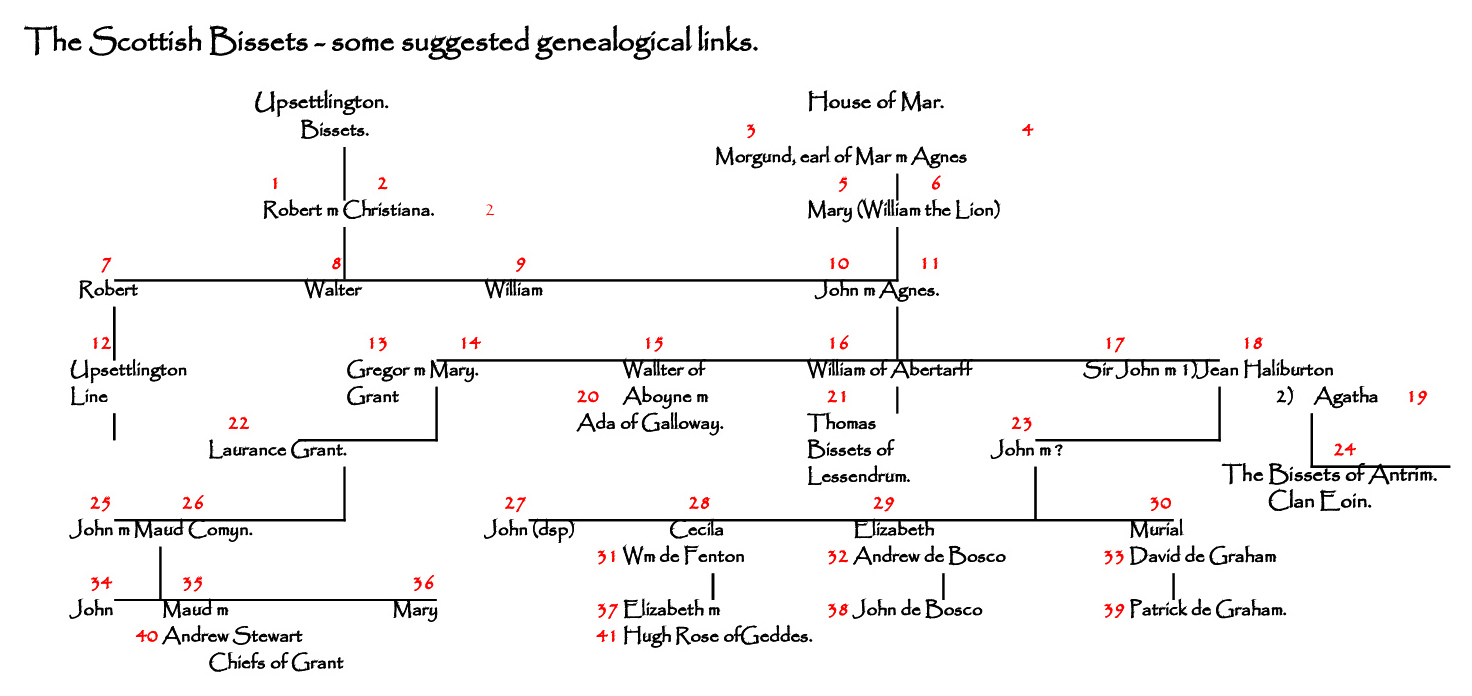

The relationships between these 40+ individuals can be seen with a family tree diagram in figure 3 below.

Download as figure_3.pdf or a GEDCOM file figure_3.ged

Morgund or Morgund mac Gylocher, 2nd Earl of Mar, circa 1141 died before 30th March 1183. (P) he may have inherited via the Celtic rule of descent

(1) Agnes wife of Morgund Earl of Mar. she is noted as Agnes, comitissa de Mar and as such acted in her own right. This has led to suggestions that Morgund was Earl in right of his wife but as his legitimacy was upheld she more probably acted over assets which may have come as dower or were still retained by her.

( 2) Mary daughter of Mar, [b circa 1145] daughter of Morgund and Agnes – she married first the 8th Earl of Atholl and secondly the 4th Earl of Sutherland but not we suggest before she may have borne the future King William the Lion a natural daughter Agnes. It is hard to believe that either of her two legitimate husbands would have made strong objections. After all William was married to the illegitimate grand-daughter of Henry I of England.

(3) William the Lion, King of Scotland, 1143-1214. the proposition is that William as a young man was Lord of Garioch, a Royal Thanage which had previously formed part of Mar and as such had formed a relationship with Mary of Mar which resulted in a daughter Agnes (9)

(4) Robert Bisset, of 1140 AD the first recorded Bisset at Upsettlington and therefore the first recorded Bisset to be established as living permanently in Scotland. He may not have been the first Bisset to hold Upsettlington but without evidence to the contrary he must be seen as such. [c1119-c1170]

(5) Christiana Bisset, wife of Robert above and mentioned equally in the St Leonard’s Charter. She may have been the widow of Constantine of Coldingham. If so this would offer the scenario that as an important widow and heiress King David 1st, was actively involved in arranging her marriage and by so doing placed his own man in a key place and maintained the status quo in the surrounding area. [c1119-c1170]

(6) Robert Bisset., there are many Roberts Walters and Williams scattered throughout the Scottish family and it is not easy without more evidence to place them accurately. I suspect that there was a Robert as eldest son for several generations.

(7) John Bisset, who married Agnes “daughter of the king” Lord of the Aird. Wardlaw states that he was known as Lord of Lovat in 1170.

(8) Agnes of Mar, [bc1163-6] proposed natural daughter of William the Lion and Mary of Mar.

(9) Walter Bisset, the witness

to the St Leonard’s charter of 1140. [c1120-c1170]

[Assuming that this Walter was 25 at the time and if the naming pattern of Walter

continued through each generation there could have been in excess of 5 Walter

Bissets between 1140 and 1251 the death of Walter the exile or 10 if we take

the date to 1368 with Walter of Clerkington and Coulter making a potential minefield

for any historian to unravel who was who]

(10) William Bisset, also a witness to the above charter. [c1120-c1170]

(11) Upsettlington line. The Bisset line which continued until at least 1365.

(12) Sir John Bisset, [c1198- 1158] who married Jean Halliburton.

(13) Jean Halliburton, given by Wardlaw as wife of Sir John but other sources state that his wife was a Margaret who died in Bordeaux in 1244.

(14) Walter Bisset of Aboyne [c1181-1251] the Walter of the exile.

(15) William of Abertarff, [c1183- c1233] The Wardlaw MS credits him with sons Walter, Malcolm and Leonard who all went into voluntary exile in Antrim with their uncle Sir John. (13) None of this is confirmed by other sources and nothing else is known of them which does not necessarily invalidate the Wardlaw statement. He held Abertarff in 1220.

(16) Mary Bisset [c1188- ?] wife of Gregory Grant and daughter of John and Agnes Bisset and the link between the Grants and the Bissets.

(17) Gregory Grant [c1200-1249] 2nd traditional chief of Clan Grant.

(18) Lady Agatha second (or third) wife of Sir John.

(19) Ada of Galloway [c1219-c1270] wife of Walter Bisset and daughter of Roland of Galloway.

(20) John Bisset [c1213-1258] known during his father’s time as “the Younger” he inherited the great estate of the Aird in his fathers lifetime due to the “exile”.

(21) The Bissets of Antrim or Clan Eoin, The descendants of Sir John and Lady Agatha.

(22) Thomas Bisset, we know he was the heir and nephew of Walter (15) and it seems reasonable to see him as a son of William of Abertarff – from him were descended the Bissets of Lessendrum.

(23) Laurence Grant [c1230 – 1275] 3rd traditional chief of Clan Grant. May have married Mary sister of David de Graham (33)

(24) John Bisset [c1236-c1256] son of John (21) who predeceased his father. Dead by 1259.

(25) Cecilia Bisset, [c1237-c1280] eldest daughter and co-heiress of John Bisset (21) alive in 1315.

(26) Elizabeth Bisset, [c1238-c1281] middle daughter and co-heiress of John Bisset (21)

(27) Muriel Bisset, [c1239-c1281] youngest daughter and co-heiress of John Bisset (21)

(28) John Grant [c1235- 1295] 4th traditional chief of Clan Grant.

(29) Maud Comyn wife of John Grant.

(30) William de Fenton husband of Cecilia Bisset died before 1315.

(31) Andrew de Bosco husband of Elizabeth Bisset.

(32) David de Graham husband of Muriel Bisset and through her Baron of Lovat. Died about 1298.

(33) Elizabeth de Fenton daughter of Cecilia and William.

(34) John de Bosco son of Elizabeth and Andrew.

(35) Patrick de Graham son of Muriel Bisset and David de Graham. Died without issue and his sister, the Countess of Caithness, became heritable proprietrix of Lovat.

(36) Sir John Grant [c1270- 1295] 5th traditional chief of Clan Grant.

(37) Maud Grant [c1290-c1340] sister of John (37) who married Andrew Stewart.

(38) Mary Grant [1263 - ] may have married Patrick de Graham of Lovat and their daughter Mary of Lovat married Simon Fraser hence the Frasers of Lovat... Sir Simon was never the actual owner of Lovat, as his brother-in-law, Patrick Graham, survived him by about seven years. Sir Simon Fraser’s mother-in-law, who was a Graham, inherited her brother Patrick’s property of Lovat. He died about 1340, but how long she lived as heretrix of Lovat is conjecture.

(39) Elizabeth de Fenton daughter of Cecilia and William.

(40) Andrew Stewart [c1290-1335] husband of Maud Grant (38) who by his marriage and by changing his name to Grant became the 6th traditional chief of Clan Grant and the progenitor of all subsequent such chiefs.

|

Chapter 4b:

|

|