[50] Sir James Ogilvie-Grant of Grant, Bt. (1884-1888)

Ninth Earl of Seafield, Viscount Reidhaven, Lord Ogilvie of Deskford, etc. Sir James Ogilvie-Grant was born in 1817, the fourth son of Sir Francis William Grant, sixth Earl of Seafield. He resided at Mayne, near Elgin, and also had a house in London. He was educated at Harrow, and then had a captaincy in the 42nd Foot Regiment. He was long connected with the Volunteers, and became colonel of the Morayshire Battalion. He was M.P. for Elgin and Nairn from 1868 to 1874, and Deputy Lieutenant of Morayshire. He was created Baron Strathspey of Strathspey in 1884, which peerage was previously held by his elder brother, John Charles, and his nephew, Ian Charles. One wonders what he thought about his landless situation?

He was married three times. Firstly, he married Caroline Louisa Eyre Evans of Ash Hill Towers, co. Limerick in 1841, a relation of Lord Carberry. I am told by the Evans family that Ash Hill is now a show house. She died in 1850, leaving one son, Francis William, the subject of the next record. Secondly, he married Constance Helena Abercromby of Birkenbog and Forglen in 1853. Some years ago my cousin, Nina Countess of Seafield, asked my wife and I to drive her to lunch with Lady Abercromby, of Forglen. We found a large and beautiful Victorian house, with ornamental lawns sweeping down to the Devron, a famed fishing river. As may well be imagined, it was a great joy to me to meet this name from the past in person, as well as to be entertained in this supremely comfortable and peaceful mansion, set in such graceful surroundings that it was hard to believe we were, in fact, in the north-east of Scotland.

His second wife died in 1872, leaving a son, Robert Abercromby, who served in the Gordons in the Boer and Afghan wars. He left a son and a daughter. Thirdly, he married Georgina Adelaide Forester in 1875, a widow, and one of the daughters of General F. N. Walker of Manor House, Bushey, Herts. She died in Elgin, where she had a house (probably Mayne), in 1903. It is perhaps of interest to record that my grandmother and aunts used to see a lot of her at 61 Onslow Gardens, her house in London, presumably her husband's town [51] house, and sometimes there were three Countesses of Seafield in that house together, and, of course, another at Cullen House! She left her money to various charities, and Francis William received nothing from his father's decease.

Sir Francis William Ogilvie-Grant, 10th Earl of Seafield, etc. (1888)

My grandfather, Frank, was born in Ireland in 1847. His mother died when he was three, and when his father married Constance Abercromby he was sent off, as was customary, to a preparatory school. He normally spent his holidays at Grant Lodge, Elgin, with his step-grandmother, Louisa Lady Seafield, the second wife of the sixth earl.

He served in the Royal Navy as a midshipman, and then appears to have entered the Merchant Service, as a junior officer. In 1870, he went to New Zealand before the mast. It was not thought possible that he would ever obtain the titles, and at that time it was quite the thing to seek one's fortunes in the colonies; but, like so many others, he instead lost the little money he had. He made contact with his maternal uncle, Major George T. Evans, who had a farm at Waiareka, near Otago, called 'Clovon Evan'. The major had sold up Ash Hill in County Limerick as things were bad in Ireland, and emigrated. The major was related to the Maunsells, whose daughter married the sixth earl.

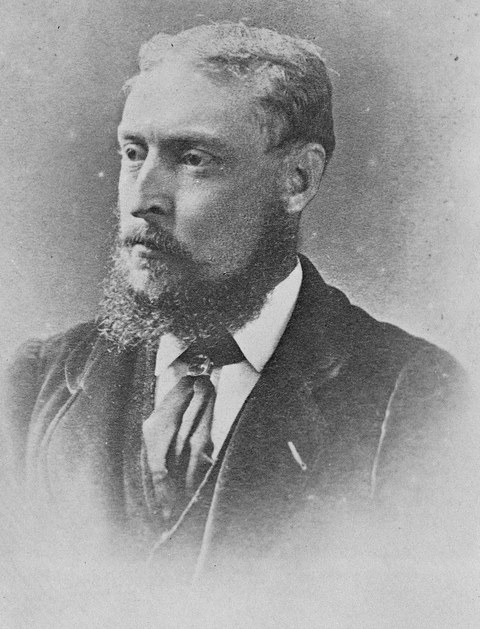

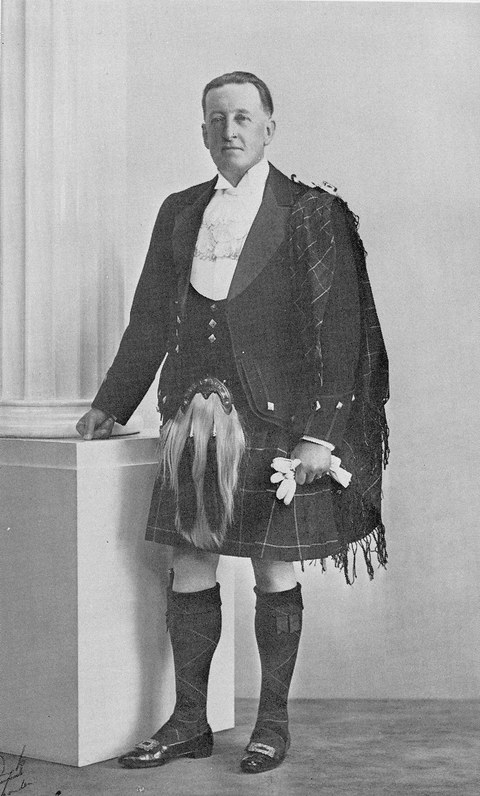

Photo of Sir Francis William Grant in 1864

Sir Francis William Grant in the 1880s

Frank bought a few hundred acres of sheep grazing at Kia Ora, near ‘Clovon Evan'. He called his farm 'Haydowns'. In 1874 he married Major Evans's only daughter, Nina, his first cousin. By all accounts, they were a very devoted couple. Unfortunately, he had to sell up soon after and lost all his capital. The market price for sheep had gone down to 21⁄2p each in modern money, so he was financially broken in spite of the help he received from his father- in-law.

He removed to the town of Oamaru, and set up as an estate agent, but this failed and so he took up any labouring work he could get, to keep his family from virtual destitution. Times were very hard for him. Nina, my grandmother, took domestic work to help out, and at this time she became interested in the Salvation Army, which close interest she kept up for the rest of her life; and I am told that she played the tambourine in the local Salvation Army band.

There was correspondence between Frank, his father, and his half-brother, Robert Abercromby. This was effected by the 'Frisco mail which seems to have run very regularly, once a week. It ought to be explained that in those days, the southern half of the South Island was the most populated and prosperous part of New Zealand, because of the gold fields. It was only at a later date that the North Island took over, and the South had its wealth mainly in sheep-farming.

His eldest daughter, my Aunt Caroline, had a number of these letters, which doubtless would have been most interesting reading today, but she lent them to [52] spiritualist in 1906, and they, unfortunately, were lost. Aunt Caroline was a believer in spiritualism and produced two large books of 'automatic writings' from relatives in the spirit world. She was, however, the family's respected 'Samuel Pepys' diarist over a period of some 40 years, which habit she must have learned from her father, Frank, who kept a ship's log type of diary, of which only three volumes exist today.

Frank continued with labouring work of all kinds, until in 1884 he became Viscount Reidhaven, consequent to the decease of Ian Charles, and his father, James, my great-grandfather, succeeded as the ninth Earl of Seafield. Frank was then helped by small financial remittances from the Dowager Caroline, through Sir Charles Logan, her lawyer. He stood for the New Zealand parliament in 1884, but just missed being elected. In 1888, he succeeded to the earldom, and the other titles; the dowager sent him a larger remittance-I think about £600 per annum.

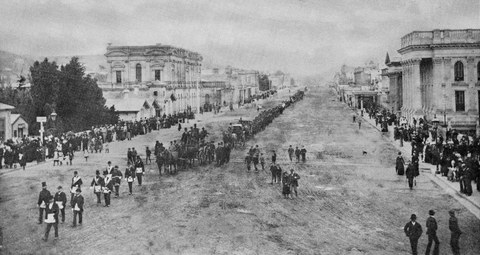

Sadly, it appears that he had for some time suffered from heart disease, and when on holiday in the Lakes, and looking round one of the famous South Island goldfields in a friend's pony and trap, he became ill, and died shortly afterwards in Oamaru in December 1888, the fourth Earl of Seafield and Chief of Clan Grant, to die within seven years. The New Zealanders treated him with great consideration. He had an enormous semi-military-type funeral, attended by over 5,000 people in Oamaru. Two of his children are buried with their father in Oamaru cemetery, with a memorial stone provided by my Aunt Nina, his youngest daughter.

Funeral of Sir Francis William 6th Dec. 1888, Omaru

His children were: James, the subject of the next record, born in 1876; Trevor, my father, born 1879; John Charles, born 1887, died 1893; Caroline Louisa, born 1877; Sydney Montague, born 1882; Ina Eleanora, born 1882, died 1893; and Nina Geraldine, born 1884.

My aunt Nina, Lady Knowles

My aunts Lady Sydney Montagu and Lady Caroline Louisa Ogilvie Grant about 1899

Aunt Caroline in the uniform of the ASC 1918

His wife, Nina, was born in 1847, and died in Hove, Sussex (England) in 1935. She was buried in the Evans mausoleum in co. Limerick, Ireland. Before we leave Frank we should set down briefly a few further details of his daughters and his wife. Aunt Caroline, the diarist we have touched on: she remained a spinster, but not from choice. The man she liked was killed by a train in Egypt, but she longed to have a home of her own. She lived with her mother and her sisters as convenient. She was the most comfortable and practical aunt, especially for a small boy.

Nina Geraldine was my most successful and distinguished aunt. She married Sir Lees Knowles in 1915. He came from an old Lancashire coal-owning family, and did a great many things worth recording. He was M.P. for Salford West from 1886 to 1906. A considerable athlete in his youth, he later took a great interest in hackney ponies. In fact, his competition prizes are still contested for each year. He was a barrister of Lincoln's Inn, and O.C. the Lancashire Fusiliers. He was a recognised expert on Napoleonic matters, and wrote a number of historical books, such as Minden and the Seven Years War, and [53] The Corps Students of Heidelberg University, which latter was where he, in fact, had studied. His main residence which I knew, was at No. 4 Park Street, London; he also owned an estate and two houses near Manchester, called 'Westwood' and 'Turton Towers'. After his death, Aunt Nina brought some of her Evans relations from New Zealand to England, hence we have the pleasure of having them here today.

L-R Sir Lees Knowles and his wife, my aunt Nina; my grandmother the 10th Countess of Seafield; my aunt Caroline; my great uncle Trevor Evans about 1910.

Maurice & Stanley Evans, in a carriage outside Cullen House. About 1910.

My Aunt Sydney was my most unusual aunt, in fact, even Aunt Caroline did not understand her. She seemed to me to be very prim and reserved, no doubt the loss of her twin sister, Ina Eleanora, had affected her. She married the Rev. William Spring Rice, B.A., in 1912. He was rector of Sympson, Buckinghamshire, and died in 1919. She did not stay with her husband because his niece ran the property and acted as housekeeper, leaving Aunt Sydney in the position of a non-paying guest, which she strongly objected to, but without avail.

We have read how my grandmother came to England in 1902. Until her death she lived in various rented houses and rooms, moving around from Malvern to Caterham, to London and Sussex, with her daughters, or without. They never stayed long in any one place. She was a distinguished and unusual character. She always wore black with a jet rosary round her neck, and her black hair was long and drawn down over the left breast in ringlets. She continued her charitable works. I can remember hungry children coming to the back door of Lismore Lodge, Twickenham, in 1915, and being given food. At the age of three I can remember Lismore Lodge quite well, and as a vague shadow, my Uncle James, the 11th Earl, leaning on the mantlepiece on one of his rare visits to his mother when on army leave. For some reason this fabulous figure seems to have rather disappointed me. It must have been very shortly before he was killed on the Western Front. My grandmother always maintained her interest in and contact with the Salvation Army.

Perhaps one might record here that she donated a small writing desk to the Russell Museum before she left New Zealand. This may have been from either her Irish family, or from her husband's Grant family, but, its origin is, unfortunately, not known. However, it is still on show there, with a note to say it was donated by my grandmother. She had removed to Whangarei from Oamaru after my grandfather died; this is near to Russell which was the original capital of the colony. The area is north of Auckland.

Captain Sir James Ogilvie-Grant, 11th Earl of Seafield, etc. (1888-1915)

James was born in Oamaru, South Island, New Zealand in 1876, where he spent his early years. He succeeded to the earldom and the chieftainship in December 1888, at the age of twelve. He then went to a private school at Aikaroa, and in 1890 he went to Christ's College, Christchurch, the capital of the South Island. Next he went to Lincoln College, to study agriculture and forestry.

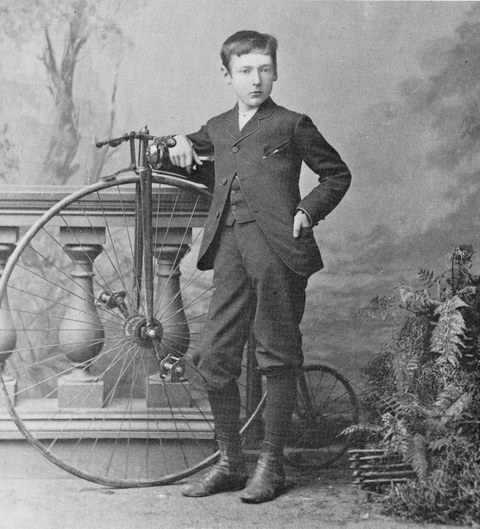

[54] There is a photograph of him with a small penny farthing bicycle, and I have discovered that this bicycle was sent to him by the Dowager Caroline. The sons of my grandmother had few, if any, toys. There was no money to spare for such things, so the bike will have been a red-letter present.

After the family left Oamaru and went to live in Auckland in 1895 at the top of the North Island, James served in various volunteer military units, such as the Canterbury Rifles and the City Guards, and, in fact, he maintained an interest in military matters all his life. When he came to England he joined various volunteer units. At school he is reported to have been quite a runner, winning many sprint events.

He received a number of congratulatory messages of goodwill from Clan Grant societies, and particularly from the one in Grantown on his coming of age in 1897, as well as having receptions held for him in New Zealand. The dowager, however, did not encourage any Speyside rejoicing, as she said she had retired from public life.

In 22 June 1898, James was married to Nina Townend, eldest daughter of Dr. Townend, M.D., an ambitious general practitioner of Christchurch, at St Barnabas's church, Fendalton, N.Z., in the presence of two friends. The doctor was a friend of the family. On 15 October 1898, the young couple travelled by the Oceana to London, where they stayed for two weeks visiting friends. It appears that Sir Charles Logan met them on arrival, and, it is reported, remained in close attendance upon them, so that he could let the dowager have full reports, no doubt. There is a rumour that James paid a secret visit to Grantown, and saw the castle from a distance. However that may be, the fact is that after a few weeks, they returned to New Zealand. It is thought that during this time the doctor had been giving the couple an allowance, and it may be that James secured another allowance from the dowager, through Logan.

Sir James as a young man c1900

In a few months, rather surprisingly, the couple again returned to London, where they seem to have lived for a few years. James joined a Volunteer Army Unit, and was stationed in Bedford and Colchester, and he did training at Bordon and Tidworth from time to time. In about 1905, they went to live in the South of France and in Florence in Italy, because James said he could not afford to live in England on the pittance he received. There are snapshots showing that he also went on a visit to Egypt.

In 1906 their only child was born-my cousin, Nina, the late Countess of Seafield. She was born in Nice. James was so happy, and sent almost daily letters to his mother and sisters in England. At that time he must have achieved a rather improved allowance from the dowager, as he was able to live rather more comfortably, and had the services of a maid, Miss Street, who remained. with the family for many years until the 1920s. They next went to live in Queen County, Ireland, and alternated between there, London, and Florence for the next few years.

[55] Early in May 1907 James had his mother and sisters to stay with him in Ireland, to help look after little Nina, his daughter, while his wife had to go to London for specialist treatment, and he had to go to do his military training. They liked the old rambling house at Ballacolla in Queen County. This is the first time he had had his relations to stay as far as I know. They stayed till mid-June. It is worth quoting Aunt Caroline's diary entry about the journey:

1st May 1907 (Mr. Cadogan's birthday)

A fine day though windy. We got to Holyhead (tickets 25/6 each) at about 4 a.m. and went on to the boat. We did not feel one bit ill although the crossing was very rough. Arrived at Dublin about 7.30 a.m. Had breakfast 2/- each, and drove to Kingsbridge Station and left by the 9.15 train for Abbeyluise where we arrived at 11.15. James was waiting with the jaunting cart. The luggage being sent on afterwards. We had a nice drive of four miles to Ballacolla. The house is very nice. An old rambling one. Baby has such a nice large nursery. James adores her more than ever. We were ready for lunch and then saw round the place. Rain followed. James had a lemur called 'Jackie' as a pet.

James even went as far afield as Barbados, and Nina, his wife, went home to New Zealand, for her father's funeral.

This brings us up to the start of the Great War in 1914, when James was commissioned into the Cameron Highlanders (5th Battalion), commanded by Lochiel in 1914. The battalion went to France in 1915, and were held in reserve for a time during the battle of Loos when great losses were suffered; James was made a company commander, of 'A' Company. The whole battalion was then down to only 101 men (all ranks), instead of the 800-1,000 it had started with. Then the battle of Ypres commenced, and James was in command of the battalion, being about the only trained officer left. One morning he went into the very shallow trenches, full of water, and with a low parapet. He was as brave as a lion, Lochiel had said. The enemy were on the famous Hill 60. He was visible to the enemy, and was shot in the head by a sniper; he died some hours later, in a field hospital behind the lines. He was buried at the British cemetery at Poperinghe, called Boeschepe. He was a great loss to all. His little daughter, Nina, then became the Countess of Seafield, and my father, Trevor, his brother, inherited the Grant honours, and became Lord Strathspey and 31st Chief of the Clan.

It would be appropriate here to speak of Nina, 12th Countess of Seafield in her own right. In 1930 she married Mr. Derek Studley-Herbert, who died in 1960. Nina had two children: Ian Derek Francis Ogilvie-Grant, born in 1939, the present Earl of Seafield; and Pauline Anne Studley-Herbert Ogilvie- Grant, born in 1944, and now married to Mr. Hugh Sykes. Nina was a really exceptional hostess. She had a wonderful knack of making her guests feel very much at home. I have certainly never encountered such hospitality as she dis- pensed on the many occasions she had us to stay at Cullen House or at Kinvechy Lodge. I, for one, always felt I was completely at home when staying with her.

Nina, late Countess of Seafield in her own right

(photo: Harry Beson, Camera Press, London)

[56] I ought to record here that one day at Cullen, Nina asked me, much to my surprise, if I'd like to see her mother, my Uncle James's wife. Well, I'd never seen this relative, only heard a great deal about her, and I had no idea where she was. I only knew that she went off on cruises up the Amazon. I was taken to see her in the large bedroom overlooking the Cullen Burn. I also met her on another occasion, when she came down before dinner. A charming, frail old lady; she knew who I was, but when I asked her what happened to her sister, May Townend, to whom my father was engaged in 1902, I regret to say I failed to obtain any clear information. She was buried in the grounds, near Cullen church.

My cousin Nina liked America very much, and had many American friends; she spent much time in the States. She also had a property in Nassau in the West Indies. I had the pleasure of staying a night or two in her lovely flat in Paris, with a recording studio adjoining, but not, unfortunately, when she was present. We have also paid many visits to her penthouse-type flat in Belgravia, London.

It was a great loss to us when she died in 1969. She was buried in the front of Cullen House. I attended as a mourner. Mr. Cyril Grant of Worthing, Sussex, arranged a memorial service for Nina at the Presbyterian church there, and asked me to give an address, and I think it may give a picture of my cousin if I quote it here:

I am going to try to give you a brief picture of my cousin, the late Countess of Seafield as I knew her. I will refer to her as Nina, because that is the name she liked to be known by. She was a completely charming figure with an unobtrusive and modest but nevertheless magnetic personality. Everything seemed to revolve around her. She seemed to be the complete master of the situation all the time and in bearing the load of her heavy responsibility for the magnificent and very old patrimony with which she had been endowed. She had great loyalty towards and from the numerous staff of retainers and experts she had built around her. She was very considerate to other people, never hectoring or bossy. She seldom put pen to paper but preferred word of mouth and particularly the telephone. If she said something she usually meant it and so all knew where they stood. There was therefore little uncertainty or change of mind. She loved music of which she was a patron, as well as other forms of art. She was easy to talk to, but often very difficult to pin down. She had a skill for rapidly disappearing in order to avoid an issue. One only knew one side of her life. She loved, perhaps best of all, people about her. She was a really great hostess, as only those few with the facilities can be. She produced a feeling of zest and gaiety with no regimentation. All you had to do was to fit in and enjoy yourself with the minimum of inconvenient cere- mony. You would meet at her parties simply everyone. Of course there were assorted millionaires, princes, earls down to ordinary professional people and her employees. Nationalities ranged from America, through Europe to Nepal. In fact one never really knew who would turn up, apart from a few regular intimates. It was difficult to avoid over-eating and over-drinking, but a day on the moors with a gun, or on the river with a rod soon put that right. She took great trouble to see that her guests had all they wanted. She gave the impression of always being very busy, and the best way to have a chat with her was to visit [57] her bedroom after breakfast, but even then she was constantly on the telephone with notebook and pencil arranging orders for the day, propped on pillows looking particularly charming and rested.

She was very kind in helping people out of trouble. She had a great sense of drama and thoroughly enjoyed creating a situation or an argument, in which I never knew her to give way on, even if she was not wholly right. This was just fun. She was very quick and observant and this gave vent to her great sense of humour, when, for example she overheard some word she was not intended to hear.

Her funeral was lovely. It was raining, but old Cullen church had so many flowers that Banffshire and Morayshire must have been cleaned out. Mr. Guthrie, the minister of Cullen, and an old friend, performed a most moving ceremony. He could always be relied on to come up trumps. During a prayer, I was impelled to look round to the south window in this 14th-century kirk, and there I saw the sun streaming in. I thought that some people might have claimed this as a vision, a good one, that all would be well, but, of course, I realised no vision could bring Nina back to material life. She was carried out of the east door on the stalwart shoulders of six of her people, keepers, foresters, chauffeur, and the like, followed by a tenant in Grant tartan piping that so exquisitely beautiful, but so sad, lament The Flowers of the Forest', followed by Ian, her son, Pauline, her daughter, Mary (Ian's wife), and myself, followed by a select company of mourners. I could scarcely refrain from weeping, and I was told afterwards that I was not the only one. Nina was laid to rest in the large rose-bed outside the main entrance to Cullen House. This in itself typifies what I have tried to express, which is that Nina was no ordinary person. I remember her for her sweet charm, magnetic elevating personality, and her kindness. My family, Michael and Amanda, my wife, Olive, and I feel we have suffered an irreparable loss, and I can only wish that I had had more opportunities to get to know Nina better than I did. For many it must be the end of an era.

My cousin, Ian (known as 'Ginger') then inherited the Ogilvie titles from his mother. He continued the tremendous family interest in forestry, both in growing trees from seed and re-planting. He had greatly assisted his mother in this enterprise. To give an idea as to its size I recollect that at his 21st birthday celebrations I was told that 13 million trees had been planted since the end of the war. His 21st birthday party was a stupendous affair. We had very kindly been invited to stay at Cullen House. Apart from food and drink for a great many guests, most being local people, there was an enormous bonfire. We were lucky enough to spend several Christmas and New Year holidays with them at Cullen, all of which were enormous fun.

Since the sale of Balmacaan Urquart Estates in 1946, the following Grant estates have been sold at various times so far as I can ascertain. I list them in no particular order. (An estate means a property of around 8,000 acres upwards, and generally comprises a mansion house or shooting lodge, one or [58] more farms with buildings, houses and cottages, forestry plantations, grouse moor, and possibly some red deer stalking and salmon fishing.) The list includes Carrbridge, Muckrach, Lochindorb, Forest Lodge, Tulcan, Easter Elchies, Delfer, and Rothes. Thus of the actual Grant country, not much remains in the Seafield ownership: roughly Kinvechy and Castle Grant. Revack, which runs for about 50,000 acres from Nethybridge to past Cromdale, is owned by the Lady Pauline, and will presumably go to her son, Harry. The Ogilvie estate, which came to the Grants with the Seafield titles, is generally intact. It runs very roughly within a triangle from Keith in the south to Buckie in the west, and Banff in the east.

It should not be forgotten that whoever owns so-called 'Clan Lands' as the current proprietor, has ownership rights and can prosecute trespassers. Nevertheless, having said that, I would add that most landed proprietors are very willing to allow visitors limited access or information if they are asked. What proprietors really object to is people taking a liberty without the courtesy of a prior request.

Sir Trevor Ogilvie-Grant of Grant, Bt., The Lord Strathspey of Strathspey, 31st Chief (1915-1949)

My father was born in Oamaru, New Zealand, in 1879. Whilst he worshipped his father, who died when he was nine, he appears to have been brought up to some extent by Major and Mrs. George Evans, of whom he was also very fond. He attended the Oamaru State School with his brother, James, and then at the age of 11 he went to Waitaki Boys High School, and later to St John's College, Auckland, when his mother removed there.

My father (the 31st chief) as a young man

He was a lieutenant in the Auckland Naval Volunteer Company in 1898, when there was a lengthy press report on the launching of their new oil launch by his mother. (The launch was named Alert, and was 47ft. long, propelled by a 16 h.p. Hercules oil engine which gave her a speed of 10 knots. She cost £600 and was used to convey some sixty or more volunteers to training areas.) Subsequently my father became a lieutenant in the Nature Rifle Corps of Christchurch.

From 1900-1903, father worked for a firm of solicitors in Christchurch, and for some time lived with Dr. Townend, for whom he did confidential secretarial work. During this time he became engaged to the doctor's other daughter, May, but this for some reason was broken off about 1903. At this time he was receiving an allowance of £120 per annum from the dowager.

My father, Sir Trevor Ogilvie-Grant Bt. about 1920

My mother, Alice Louisa in evening dress about 1920

In 1905 he married Alice Louisa Hardy Johnston, my mother. Her father was born in Belfast in 1817, and was a godson of Admiral Hardy of H.M.S. Victory fame. He became a civil engineer, and at one time assisted Robert Stevenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel, both famous railway engineers. In 1856 he went to India for bridging and railway engineering in a number of states. In 1873 he went to New Zealand for health reasons, where he died [59] in 1894 in Christchurch. His wife was a daughter of the Rev. Albany Wade of Hilton Castle, County Durham. Fortunately, I have a long and complete record of his life, and whilst it is not a proper subject for report in this book I feel it is necessary for the record to state these few interesting facts. He was related to the Johnstons of Annandale, an important Scottish border family.

Father removed to Wellington, the capital city, and obtained a job in the post office money order department, where he remained until 1913, when we all came over to England. He then took a house called Wyke Lodge, in London Road, Twickenham, near my grandmother's house. Father joined the Volunteers, and did drills, as did my Aunt Caroline, who joined the Women's Volunteers. She says in her diaries that she enjoyed this very much. Most of the drills took place in Richmond Park.

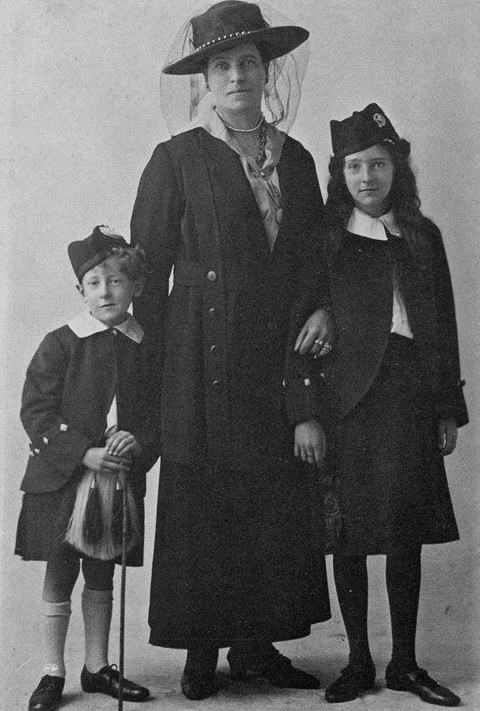

Myself and my sister Lena about 1913

Myself and my sister Lena with our mother about 1918

Myself and my sister Lena with our mother about 1921

In 1916 we removed to a house I have very happy memories of, at 2 Carlton Road, on Putney Hill (it still stands today as I write). The house next door was that of Sir Oswald Stoll, the famous theatrical producer. His house was bombed flat in the 'blitz', and most of the other houses have been replaced by large blocks of flats. I went to Glengyle House School, a few doors down the road. My sister went to the Girls' High School, which was behind our garden. Meanwhile, father was commissioned into the Army Service Corps, and became a gas instructor amongst other things. I remember he was posted for a short time to Bath and to Prees Heath, Cheshire, and he did O.C. Troops duty on trooping vessels.

Then I was sent to Wellesley House Prep School, Broadstairs, which is now combined with St Peter Court School. Then in 1921, much to the trustees' annoyance, my parents took me away with them for a year's trip to Australia and New Zealand, an unforgettable experience for a small boy. We were very well treated in both countries, free rail passes and the like. I stayed for a time in Paramatta, Sydney, with some kind clans-people called Beresford Grant.

To get back to my father: he took his seat in the House of Lords, and spoke on the cause of the Colonies. He wrote a book on 'Colonial Representation in Parliament'. The House was then a very different place from today. There were, of course, no life peers or peeresses in the Chamber, and the attendance was about half today's average. I suppose the introduction of peeresses was one of the greatest innovations, akin to women doctors being recognised by the B.M.A. in the last century, and to giving women the parliamentary vote in this century. Shortly after the war, my father got himself elected to the Wandsworth Borough Council, representing a Putney ward.

Around 1930 my parents built a house (now demolished and replaced by two bungalows) in Rottingdean, near Brighton, and father more or less retired from public life. My mother died in 1945. This was a terrible shock to my sister and me as she had been a very powerful personality. Father was not at all fit, and came to live with my wife and me in a cottage we then [60] rented on the Southwick estate, near Portsmouth. In 1947 he married Mrs. Capron, a widow, who we had known for many years. They both died in 1949. Father was very proud of his heritage, but he did not know Scotland, and had no opportunity to do so. I remember him particularly for his kind cheerfulness to all. He had one son, Donald Patrick Trevor (myself), born in Wellington, New Zealand, on 18 March 1912; and one daughter, Lena Barbara Joan, born in Wellington, New Zealand, on 2 July 1907. She married Herbert Frank Onslow in 1934, who died in 1970. They had one son, Roger, who is married and has two daughters. He is a professional filtration consultant engineer.

Sir Patrick Grant of Grant, Bt., The Lord Strathspey, 32nd Chief (1948- ).

This is me, what can I say about myself? My official data is best read in Who's Who. Readers will have noticed that the name 'Ogilvie' is omitted from my name. This is because I hold no Ogilvie titles; these are all held by my cousin, the Earl of Seafield. When I went to see Lord Lyon, King at Arms, about matriculating my arms after my succession, he asked me whether I wished to be Chief of the Ogilvie-Grants, or Chief of the Grants. Well, I quickly thought that the Ogilvie-Grants could be numbered on one hand, whereas the Grants could run into hundreds of thousands; so, naturally, I plumped for Grant of Grant, omitting the Ogilvie. Hence my arms, unlike my father's, have no Ogilvie quarterings, but they do have the little quartering in the top left-hand corner, of the Baronets of Nova Scotia, 1625. I, of course, lost the complicated distinction of being able to wear two tartans – the Ogilvie, rather a pretty bright little sett – and the Grant, both at the same time! My cousin, the Earl of Seafield, could do this, but does not, and Sir Ewan Macpherson-Grant of Ballindalloch can wear the Macpherson and the Grant tartans, dependent upon which clan country he happens to be in at the time. This necessitates a quick-change act or reversible garments, as the Highland dress cognoscenti have not yet been able to finalise the decision as to whether two entitled tartans setts should be divided east-west, north-south, or equatorially when worn as one garment.

Perhaps I should say that I am the fifth Chief in succession who has not owned any Grant lands at all, and these five are also remarkable in that none of them appears to have wielded any of the national power that former Chiefs exercised, a power that went with the possession of the land they controlled. I am perhaps singular in that I am the first Chief who has had continuous gainful employment. I was lucky in that I was stationed in Edinburgh from 1948 to 1961, and had the opportunity to travel all over Scotland. I took the opportunity to get to know my cousin, the late Countess of Seafield, by calling upon her whenever the opportunity offered. I need not add that she always was most welcoming and hospitable. Thus I was able to gain some knowledge of my forbears.

[61] In 1938 I married Alice Bowe, daughter of Dr. Bowe, late of Timaru, New Zealand, who retired to Switzerland, where he died. His widow, Mrs. Bowe, and her daughter, Alice, came to reside with Mrs. Lucius Gubbins, Mrs. Bowe's sister, in her rather splendid and superbly-staffed mansion at 55 Blackwater Road, Eastbourne. This marriage was dissolved in 1951. From this marriage. I have three children. They are James Patrick Trevor, born in 1943, who lives with his wife and three daughters at Perth in Scotland; Geraldine Janet, born in 1940, whose marriage to Mr. Neil Cantlie was dissolved some years back, and who lives mainly in London; and Jacqueline Patricia, born 1942, who lives with her husband, Malcolm Hutton, in Kincardinshire, Scotland.

In 1951 I married Olive Amy Grant, only daughter of the late Wallace Henry Grant of Norwich and Northampton, and by her I have two children: Michael Patrick Francis, born 1953, who lives and works in London with a firm of chartered surveyors; and Amanda Caroline, born 1955, who works in London. as a graphic designer.

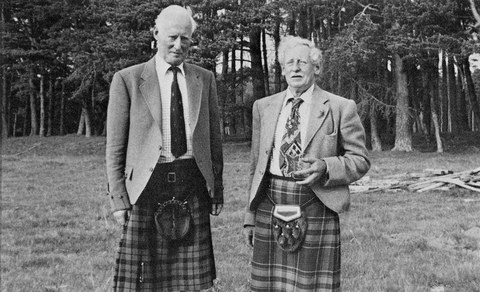

A family group, photographed in Scotland. From Left to right: my eldest son James, my daughter Amanda, myself, my wife Olive and Michael, my youngest son.

When I accompanied my parents and sister, Joan (who died on 4 February 1981), to the Antipodes in 1921, there are a great many memories fixed in my mind of this tremendous experience for me, only a boy. We travelled out in the T.S.S. Euripides, a large passenger liner which had hundreds of emigrants on board; and I can still feel today the magnificence of steaming along the so-called 'Roaring Forties' from Durban, where we coaled ship by the power of hundreds of black women, carrying baskets of coal on their heads up a gangplank from the wharf and into the coal bunkers, a real basket chain.

The strong winds of this 40deg. latitude, with an intensely blue and white sky, and the brilliant sun shining on to the blue sea, large swells breaking into whiter than white foam (an unbelievable whiteness), and the whole occasionally enlivened by spouting whales, shoals of flying fish breaking out of the sea, and, of course, always one or more albatrosses riding a thermal near the stern to port or starboard gave me unforgettable memories.

I had a lovely month in Sydney, Australia, where I stayed with a fine family called Beresford Grant (mentioned above, p. 59). Mr. Beresford Grant was an estate agent; he and his family lived in a large bungalow in the wilds of the country outside Sydney at Parramatta. I was allotted a bed on the veranda which surrounded the house in the open air. One was awakened in the morning by the strange sounds of Australian birds and other livestock. Then we spent about eight months in the North and South Islands of New Zealand, and I attended a school in Wellington.

We travelled back in an Aberdeen and Commonwealth line cargo ship of 10,000 tons called the Port Hunter. There were a few other passengers. We went past Easter Island, famed for the mystery of its numerous and immense standing statues. Then we went through the Panama Canal with its myriads of butterflies, miasmic heat, and alligators. Off Colon the crew caught a 12ft. [62] shark – I still have some of its saw-edged teeth. And on to New York and Boston and finally back to London.

It took quite a long time to re-acclimatise myself to England after the very free-and-easy ways and uninhibited friendliness of all I had met in the Antipodes; and also to lose my so-called New Zealand accent, which is caused by a change of vowel sound from the English pronunciation.

I went to Stowe Public School, Buckinghamshire, from around 1926 to 1930. The school was then only two years old. Stowe had been the magnificent Palladian-style seat of the Duke of Buckingham, who was the richest man in Britain in the 18th century. He had a private army, and the weapon racks were still in situ on the ground floor passages, off which were our changing rooms, tuck-box rooms, and boot rooms, and the headmaster's study. After I left Stowe my mother did a thing for me which has proved of lifelong benefit. During the summer holidays she sent me to the British School of Motoring for a four weeks course. She knew how keen I was on motor cycles, and she hated and feared them, and hoped to woo me to motor cars. (I subsequently owned three motor cycles and these I often had to hide from her.)

Unfortunately, my scholastic attainment was inadequate, so I was sent to a 'crammers' at Berrow, Carew Road, Eastbourne. This was a rather exceptional place; I learned there how to absorb knowledge, and passed my London Matriculation examination. The head was Mr. Wheeler, a wonderful man with young people. There were 12 boys being crammed; they were an interesting kaleidoscope: a tall Greek from Alexandria, whose parents were in Egyptian cotton; a Greek from an Athens political family; a count, the son of a Spanish grandee; a French marquis, who, incidentally, had been at Stowe when I was there; a Belgian boy; and the rest, I think, were English. We all had to change into dinner jackets every night for dinner. There was much conversation about Grand Prix motor races, Bugattis, and Alfas, being the most successful then. One of the English boys was R. G. J. Nash, who later became well known at speed events like Shelsley Walsh hill climbs, in his Frazer Nash car called 'The Spook'. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's two sons had been to Berrow shortly before I arrived.

We all lived in separate bedrooms-cum-studies, and were visited by various expert and patient masters during the hours of incarceration when, believe it or not, we really had to work and absorb knowledge like sponges do water, in the various studies of Latin, English, mechanical drawing, physics, etc. In our free time, however, we could do what we liked. Most of the boys had cars, generally 1924 models bought for around £5 each. They all went very well, except when the hoods blew off in high winds, or the steering wheel came off in one's hands! I had an old motorbike; it was not until 1934 that I bought the first of long series of assorted motor cars. It was a 1923 Standard 11.9 h.p. open tourer, which cost me £7.50. I blew up the engine one day, and drove to Brighton, 25 miles away on half of one piston, and got a replacement engine [63] fitted from a 1924 Standard for £5. I used to take my particular friend around on my motor-cycle pillion. He was an only child, who lived in a rather magnificent house in Kent, and had built his own wireless transmitting station, and, believe it or not a Baird television receiver, in 1930! At the end of each term. we ran a dance at the Cavendish hotel, where we invited particular girl friends who had to be vetted by Mr. Wheeler.

I then studied with some land agents in London, and in Lewes, East Sussex, to become a land agent and surveyor. In February 1938 I joined the War Department Lands Branch, with whom I remained until I retired in 1972. Shortly after the commencement of the war in 1939, our Lands Branch had to commence an enormous expansion, and we were all given emergency com- missions as lieutenants, and then granted temporary ranks, according to the jobs we were allocated. I advanced through officer grades to lieutenant-colonel, when I was posted to Scottish Command. We were not, in fact, de-commissioned to civilian ranks until two or three years after the cessation of hostilities. The reason that lay behind our transformation to uniform from mufti at that time was to prevent us being conscripted, in which event the army would have been left with virtually no land agents. It also facilitated our access to military establishments. We were treated as civilians in terms of salary and discipline.

I have been retired since 1972, and since then have, fortunately, been kept busier than ever. Apart from gardening and sailing there is the House of Lords sittings, which I attend as often as possible. In the last five years a tremendous surge of interest in the Clan and individual Clans people's antecedents has emerged, particularly from people in the United States of America, New Zealand, and elsewhere. This has given me additional interest and much new work. Through the kind generosity of people in North America, we have enjoyed several most enlightening and strenuous visits to various States, and one to Canada, mainly for the purpose of being honoured guests at functions and Highland Games, all beautifully produced.

It may be interesting to outline how things have changed since the end of the Great War (1914-1918). At that time horse traffic was still in general use. You saw enormous coal carts, shaped like a bath, and milk floats containing a galvanised churn with a tap from which the milkman drew to fill jugs or galvanised measures, according to the householder's requirements. If you wanted a parcel, or, in fact, any article from a piano downwards, sent anywhere, the trick was to put a card marked 'C.P.' in your window. 'C.P.' stood for Carter Paterson. (This old firm is now embodied in the giant removal firm, Pickfords.) Every day a horse-van with a man and boy used to travel the streets, and when they spotted the 'C.P.' card, in they would come, weigh the packet, charge you, and you could forget it. It would get to its destination safely. In those days there were five mail deliveries every day, the last one being at 10 o'clock at night. Telephones were very few, but we had one in 1916. The telegram was the normal method for quick messages to be passed-and it was [64] quick. Delivery was effected by means of a telegram boy on a cycle from the post office, and he would wait for any return reply. There might be one or two motor cars or lorries or steam wagons in a street, but the rest would be horse- drawn vehicles. Barrel organs were a daily source of rather strident music, which competed with the shouts of old bone and rag men with hand barrows, or donkey carts, and beggars of all sorts. Small bare-footed boys ran in the roads with soap boxes, not for oratory or political purposes as today, but with wheels fitted for the purpose of collecting horse droppings with brush and shovel. The Boy Scouts bugle and drum bands were a frequent cheering sound which one misses today.

Before the Second World War, agriculture was in the doldrums. Good farm land could be bought for £4 per acre-today the same land is over £1,000 per acre-and salaried jobs in my line were hard to come by. Agricultural wages were £1.65 per week for ploughmen and tractor drivers, the highest grades; but beer was only twopence a pint, petrol under fivepence a gallon, and Players Medium cigarettes under fivepence for twenty. They are now £1 or more, so the wages were not quite so bad as the figures seem.

There is no doubt that the past 50 years have greatly eased nearly everyone's life, even if people are not wholly contented. But I am one who believes that a pair of stout shoes, full shopping baskets, machines, and other luxuries do not necessarily make for happiness. This is proved by the great industrial discontent today. Has progress been too rapid?

It is easy from the foregoing to imagine how life has changed for all in the Highland clan territories, and particularly for those who went to live abroad, notably in North America, where standards of living, in the modern sense, are rather higher than in the 'Old Country'. The New World has certainly been a land of considerably greater golden opportunity. All the more credit to those who emigrated, as they have certainly had to work for the great rewards they have won.

Myself with Colonel John Grant of Rothiemurchus, 1981.