Marjory Lude appears in Fraser’s “Chiefs of Grant” as an enigmatic figure whom he was obliged to include in his narrative in order to explain later events.

The burden of what he has to say is to be found in Volume I, page 61:

…. in 1473 Marjory Lude, a widow, styling herself "Lady of half the barony of Freuchie," alienated her lands of Auchnarrows, Downan, Port, and Dalfour to her "carnal son," Patrick Grant. Vol iii, of this work, p. 30 This Patrick was surnamed Reoch or Roy, and died before 2d December 1508, without male issue, as his heir in 1565 is stated to be a grandson, Nicolas Cumming…..

Fraser insinuates, erroneously, that her son Patrick may otherwise be “Patrick mac Ian Roy” who we actually know to be the progenitor of Tullochgorm and the son of either the wife or daughter of Baron Lamb of Tullochcarron.

Fraser also says (Introduction (p xxxv)):

Sir Duncan Grant appears to have possessed only the half of the barony of Freuchie, the other half being the property of Marjory Lude. She, on 28th July 1473, granted a charter to her son……

This is simplistic. Elsewhere it is clear that he does understand at least some of the principles of feudal land ownership, but he fails to apply them here – being seduced perhaps by a marginal grandiosity on Marjory’s part. When legal (and tax) problems arose there was never any doubt that it was the laird of Grant who would manage their sorting out. There are many layers of feudal tenure and after every death the heir still needed the king’s say-so to “enter” and to be “infeft”.

We certainly can pin point who Marjory was; how she came to be “Lady of half the Barony of Freuchie” can also be identified with a more than fair degree of confidence.

Part I: Who was Marjory Lude?

Today with the vast resource of the internet it is easy to establish who Marjory Lude must have been – by which I mean she is not specified in existing records.

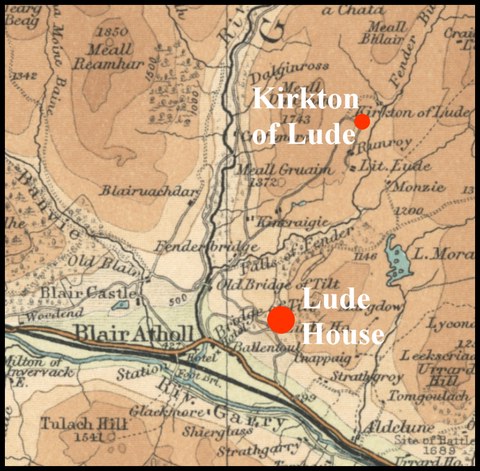

Origin of the name Lude: was a very large estate close to Blair Atholl. Lude House (doubtless not the same building as 550 years ago) still exists and the extent of the estate can be seen from the Kirkton of Lude well up the valley of the River Fender, over two miles away from Lude House.

Base map: maps.nls.uk

The Family of Lude: So too there is no mystery about the family of Lude. The House of Lude had branched from the main Clan Donnachie line 3 generations earlier, the progenitor being Patrick who held Lude from his father – the Duncan “de Atholia” who was the namefather of the Clan Donnachie – the earlier name for the Robertsons. Duncan was born 1328x35 so Patrick was probably born 1350x60. His grandson John was born shortly after 1400 dying in 1476. His wife was Margaret Drummond. For a full background understanding of the ancestry of the Clan Donnachie (later aka the Robertsons) see my paper www.academia.edu/42889850.

From this we should note, inter alia, that the use of the name Robertson as a surname only began in 1459 on the death of the eponymous Robert. It may be that after that time the family of Lude adopted the name Robertson, but clearly that is NOT appropriate to Marjory due to anachronism.

Marjory Lude’s place in her family tree: We have seen above that Marjory Lude was making provision in her widowhood in 1473, so there are two possible scenarios:

Given that John’s wife was Margaret and that Marjory is a pet form of Margaret, we could imagine Marjory being John’s firstborn – born, say 1425 and marrying c1440. This would have her selling her stake in Inverallan aged 48 and her son Patrick c68 at his death.

On the other hand, we may note that John died in 1476, so 1473 would be a fine time for his younger sister to be settling her affairs in her old age. In these circumstances she may have been born say 1410, marrying c1425, making her son Patrick rather over 80 when he died.

Of these I prefer the former scenario and to presume that this was in the reasonably immediate wake of her husband’s death. The fact that it was she who inherited would appear to have been a stipulation in the marriage contract. If I am right then Marjory was still young enough to marry again and move away from the area. Other dating considerations also much favour the later scenario (see below).

Marjory’s husband: Given that her son was a Grant, we have no alternative but to accept that her husband was a Grant – but we can be confident that we do not know his name. So how did he come to “own” half of “Freuchie”? We will return to him later.

Part II: Marjory’s possessions

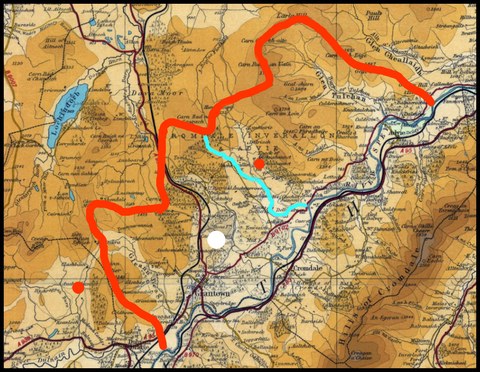

We should begin our examination of this by recalling that in 1316 Sir John Grant was awarded half of Inverallan. Here is a map of my interpretation of Inverallan at the time.

Base map: maps.nls.uk

Note the small red dot roughly in the middle: this is “Auchnahannet” the site of the “mother church” for the religious structure which predated Catholic “parishes”. The keen reader will note another to the west of the area (I simplify) which was the mother church serving at least that part of what is now Duthil parish north of the Dulnain River. The white dot locates Castle Grant.

[There is a map of the Cromdale district dating to around 1950. “Inverallan” can be interpreted as that part of the parish west of the Spey. There were major reorganisations of parishes following the Reformation, including the moving of boundaries to suit the substantially different circumstances of the times. The NW boundary (with Forres) does not conform with the topography, so we may overlook this. So too it is unlikely (though possible) that the NE boundary was marked by the Geallaidh. Far more likely that it was the watershed between it and the Burn of Tulchan – and this is how I have represented it. This is the reasoning for my map.]

The Grants’ half

The division into two of the parish was arbitrary and doubtless dates to 1316 by which time written charters were the norm and so the choice of the burn Allt Breac looks as if it was arbitrary and convenient. I have chosen one western tributary for illustrative purposes, but it is possible that the boundary went straight up to Sgòr Gaothach. It is clear that giving this land to Sir John Grant was a deliberate part of the “herschip” of the Comyns with the intention of depriving them of Babbet’s Tower (that part of what is now Castle Grant which had been a Comyn stronghold).

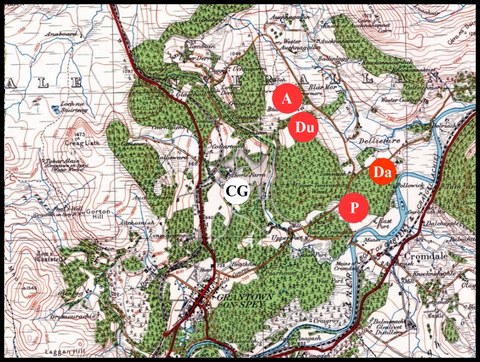

We can now have a look at Marjory’s “possessions” in context. Marjory’s estate is shown in red: Achnarrow, Dunan, Dalfour and Port; for context Castle Grant is located in white:

Base map: maps.nls.uk

And here we can see that they do indeed amount to about half the “Barony of Freuchie”, but we note that the barony is no more than the original half of Inverallan (which is as it should be, given the date). Only later were other lands which the Grants had acquired united into an official free “Barony of Freuchie”.

Part III: Marjory’s link to the Grants

As we have seen it is likely that Marjory married in c1440 though just about feasible that it was c1425.

If it had been 1425 then her husband would have been born c1400x5, she would have arrived in Freuchie in the middle of the feud with the Comyns and just after the Clanallan had been installed at Dunan/Downan. As Patrick Reoch seems to have been normally resident at Achnarrow. This appears to have put Marjory right on the front line. Many a father would have baulked at such a situation. [The Clan Ciaran was long associated with Achnarrow, but clearly they will not have been moved there until 1508, so they may have been at Dalfour or Port before that.]

If on the other hand she married in 1440 then her husband would have been born c1415x20 and she will have arrived in Freuchie when the feud was all over. So this reinforces the position taken earlier and I will proceed on this assumption.

Where her husband fits in

If her husband had been born in 1415x20 he would have been of the right age to be a brother of Sir Duncan, but, if so, he was certainly not the laird of half of Freuchie. Sir Duncan’s life is so well documented that it is extremely unlikely that all the MS historians would have overlooked him. So we can count this idea out.

So we need to consider Marjory’s father-in-law. He was likely born c1395 and so would have been a son of Patrick and brother of Ian Roy. But in the page on the feud with the Comyns we noted that Patrick was murdered in 1410 when Ian Roy married – so Marjory’s father in law would still have been a teenager – again certainly not the laird of half of Freuchie. Not only that but it was Ian Roy who solicited the clansmen to leave Stratherrick for Stathspey and installed them at Dunan etc. – hardly the action of someone who would install a son as laird.

Researching this topic has forced me into ground I had not examined before. Setting out the trail of evidence would be tedious, so will not be rehearsed here (though I may do elsewhere), but when we examine the distribution of parcels of land in and around across several generations, I am left in no doubt and with no alternative but to propose that it was Maurice Grant, a younger son of Maud Grant and Andrew Stewart who was given these lands – and so that Marjory’s son, Patrick Reoch, was his direct (and, as it turned out, last male line) descendant.

Deliberate obfuscation of this line

“Maurice Grant” has been much abused by later “historians”. The ‘Good’ Sir James who was responsible for the text in the Baronage of Scotland, placing him between Robert Grant the Ambassador (c1335-1394) and Sir Duncan Grant (c1413-1485). This is fatuous and has clearly been done to obscure the two murdered chiefs who were actually in the line. Here is what is written in the entry in the Baronage.

VII. MALCOLM de GRANT, who began to make a figure, as head of the clan Grant, soon after Sir Robert's death, though then but a young man. He was one of those gentlemen of rank and distinction mentioned in a convention for settling some differences between Thomas Dunbar earl of Murray and Alexander de insulis dominus de Lochaber, anno 1394. He died in the end of the reign of king James I. or beginning of that of king James II, leaving issue a son.

This is out-and-out contradicted by Fraser who writes (vol 1 p25)

Another person who may have been a member of the family is Maurice Grant. He is first named as acting on behalf of the Provosts of Inverness in rendering their accounts to Exchequer, at Berwick, 16th March 1331, and at Scone, 8th March 1333. He also rendered the account for the regality of the Earl of Moray within the sheriffdom of Inverness, at Aberdeen, on 30th December 1337. In 1340, if not for some time before that date, he filled the important office of Sheriff of Inverness, Exchequer Rolls, voL i. pp. 310, 417, 440, 465 a post similar to that held by Sir Laurence le Grant. No further trace of this Maurice Grant can be discovered after 1340, and no proof of any relationship to John le Grant of Inverallan can be established.

My estimate for the birth of Maurice son of Maud and Andrew Stewart is about 1282. So suggesting he would be active in 1394 is not feasible. But this circle can be squared. If his line followed the traditional naming pattern then he is likely to have had a grandson also called Maurice born c1332 who would have been in a position to have fulfilled the duties in 1394 referred to in the Baronage. As we can see he would have been about 60 years old – so not “a young man”!

As anyone can see, the name Maurice had never been used before by Grants. It is an Anglo-Norman name which has been used as an Anglicisation of Murdoch and other names (for which see

https://poms.ac.uk/search/) but none of these are relevant to Grants either. So this name by itself is indicative of the “intrusion” of Andrew Stewart into the chiefly line. What I have not been able to do yet is to identify the Maurice (or perhaps Murdoch etc.) to whom respect is being paid via the giving of this name. Sir James naively destroyed his own argument and Sir William Fraser was left trying to patch things up as best he could!

It is most unfortunate that Fraser does mislead deliberately. Referring to a charter he says:

William [28] Pylche was to render "forensic service" to the king, so far as pertained to Kildreke and Glenbeg, in accordance with the terms of the charter of' infeftment of Inverallan, granted to Patrick le Grant's father. Vol iii of this work, p. 10 This last clause is conclusive proof that Patrick le Grant was the son of Sir John Grant of Inverallan, as the above tenure is precisely stated in Sir John le Grant's charter of infeftment in 1316.

Setting aside Fraser’s ludicrous reference to “forensic service” (it is actually “forinsec” service), when we look at the charter while we do find the word “patris” – implying that Patrick inherited from his father – we also find the phrase “antecessor noster”, making it clear that another ancestor had held the land previous to his father. It is this ancestor, his maternal uncle, Sir John, who was first infeft by the king. So the charter actually proves the opposite of what Fraser says it does.

DNA

DNA has been the subject of much argument, especially in the form of assertions by people who think they know what they are talking about – but don’t! [See separate pages on this site.]

There are some Grants about whose DNA there is no doubt – they bear the Royal Stewart signature. Included are the late George Grant, the driving force behind the establishment of the Clan Grant Society in the US and a similar figure in Australia. The chiefly line, however, displays sufficient discrepancy as to allow some wilful nay-sayers to cast doubt on the chiefs’ own descent from this line.

What I suggest here is that the unchallenged lines actually descend from Maurice, while in Patrick we have a relatively rare and relatively substantial mutation, creating a standard statistical “likelihood” of 30%. This genetic upset is also indicated by Patrick’s small stature. The circumstances of Patrick’s conception, too, may have played a part – the mechanism is not yet understood.

Narrative Summary

When they acquired “half of Inverallan” in 1316 the Grants still held a far larger estate on the eastern shores of Loch Ness. Inverallan was ‘enemy territory’ and so they needed to fill it with trusted lieutenants. Marjory Lude came into possession of the lands originally feued to Maurice some 5 generations earlier.

Such charter evidence as there may have been is lost, but this is no great surprise as eg many early Grant charters will have been destroyed when Alexander Stewart, the “Wolf of Badenoch”, set fire to Elgin Cathedral in 1390.

Such was the nature of the feudal system that there is no dichotomy between Marjory being “Lady of half the Barony of Freuchie” and Sir Duncan still being her feudal superior.

It should come as no surprise that, like William Pylche, Maurice and his descendants do not find a place in the old MS histories. The “mother text” for the Monymusk Text and others was written in the middle 1600s. By this time Maurice’s line had been extinct for well over 100 years so was one of many easy choices for pruning to make size of the overall document manageable.

Footnote on Maud Grant and Andrew Stewart

Sadly one traditional story is a casualty of this analysis, but actually it was anyway. In the Monymusk Text, for example, it is related that Andrew Stewart courted Maud Grant in Freuchie and was protected from the animosity of other senior clansmen by the “Baron of Downan” who hid him in a cave (where he and Maud had their assignations).

The first problem is that the timescale requires their marriage to have taken place shortly after 1275 – 40 years before the Grants had their foothold in Strathspey. So, the romance could not have occurred in Inverallan, but must have been in Stratherrick.

Secondly, and sadly, there are no caves in the area round Balachearnach (now “Castle Kitchie” between Ballagan and Balchraggan farms) which was the Grant seat at the time.

Third, by the “Barons of Downan” the seannachie could not be referring to Maurice or his descendants because they were Maud’s descendants! He could have been referring, however, to the Clan Allan chieftain who held Dunan later.

It is quite likely that in Stratherrick the Clan Allan chieftains were based either at Ballaggan or at Balchraggan – and in those days farming required a substantial labour force which must have been housed. So there is no problem in principle with the Clan Allan chieftain of the day being sympathetic to Andrew Stewart and making provision for assignations on his property. It seems that it was Maud’s pregnancy which precipitated matters with the outcome which was then integrated into Grant lore.

As for the “senior members of the clan”, not only Sir John Grant but also his father John Grant were still alive and well when Maud became pregnant, so they were the only people who had any real say in anything. Had Andrew been legitimate and had lands of his own and if Sir John had had a surviving son to be his heir then things may have been different. Nevertheless Andrew Stewart was recognised as Andrew Grant before the death of his brother in law – so it looks as if Sir John was aware that there was a need for “succession planning” and he needed to get the senior members of the clan on board.

In short we can see that the legend as told has very little to do with what happened – but the underlying essence of it remains true – Andrew Stewart was only acceptable as the Clan Chief by changing his name to Grant.