REMINISCENCES HISTORICAL AND TRADITIONAL OF THE GRANTS OF GLENMORISTON

WITH SELECTIONS FROM THE SONGS AND ELEGIES OF THEIR BARDS

BY THE REV. A. SINCLAIR, M.A., F.C.S.M.

EDINBURGH: MACLACHLAN & STEWART

INVERNESS: A & W MACKENZIE

1887

Dedicated TO

IAN ROBERT JAMES MURRAY GRANT OF GLENMORISTON, ESQUIRE, XIV. MAC 'Ic PHADRUIG,

AND REPRESENTATIVE OF A LONG LINE OF ANCESTORS; THAN WHOM NO HIGHLAND PROPRIETORS WERE MORE RESPECTED AND BELOVED BY THEIR PEOPLE.

[vii] PREFATORY NOTE.

A word of explanation as to the origin of this book. The Editor’s father and brother, who were in succession Factors on the Glenmoriston Estates, made collections with the view of writing a history of the Family. To these the Editor added from other sources, and after putting the whole into shape, as it now is, gave the MS to several friends for private perusal. They all urged the publication of it, along with a few selections from the productions of the Glenmoriston Bards; and to gratify those friends — and he doubts not many more — he undertook the work. It is understood that much that would have been interesting, as throwing light on the past social condition of the people, as well as on family transactions, has been lost when after [viii] the Battle of Culloden, the mansion was burnt, and many of the family papers destroyed or lost.

The Editor has to thank all the friends that helped him, very especially Major-General Grant of the Indian Army, and Dr Donald Kennedy, the widely known American physician.

According to some genealogists, the founder of the Clan Grant – 1160 – because of a facial defect, bore the designation of “Grannda” or ill-favoured. Dr John Macpherson derives the name from Griantach, a moor in Strathspey, where it is said the Grants had their original residence; but the weight of evidence is in favour of a Norman origin, which identifies the name with Grand or Le Grand, great or valourous.

For a lengthened period the Grants held a prominent position in the North of Scotland. But with the limited information at our disposal, [2] we cannot be quite certain as to the connection between the earlier links of their genealogical chain. We must, therefore, go partly by what tradition has floated down to us, not invariably dependable, but chiefly by such contributions as family and national records offer — sometimes sufficiently scanty. But scanty as they are, they give glimpses which show that along the centuries their progress was a growing one, both in influence and affluence.

We find, for example, that, as early as the reign of Alexander III, Sir Laurence Le Grant was Sheriff of Inverness, 1258-66, and is said to have been allied by marriage to the once powerful Bissets of Lovat.

Sir John Le Grant espoused the cause of Bruce against Baliol, and was one of the “magnates” taken prisoner at the Battle of Dunbar, 1296. He was liberated on condition of serving Edward in Flanders, Graham of Lovat and Comyn of Badenoch becoming his sureties. In 1316 he obtained a Crown Charter of the lands of Inverallan in Strathspey.

[3] Patrick Le Grant was, previous to 1357, Lord of Stratherric, which, it is said, he obtained by marriage with one of the Bissets of Lovat.

Malcolm Le Grant is mentioned — 1394 — as in possession of a twenty merk land near Inverness; and was probably the father of Elizabeth Le Grant, Lady of Stratherric, and granddaughter and nearest heir to Patrick Le Grant. She disponed all her lands in favour of her grandson, John Seres, including Inverallan, which latter, in 1482, was disponed in favour of John, son of Sir Duncan Grant of Freuchy.

Sir John Le Grant, who, in 1434, was Sheriff of Inverness, is said to have married Bigla, or Matilda Cumming, and with her to have got the Cumming lands in Strathspey. This Sir John had a son, Duncan, by Bigla Cumming, who succeeded as first of Freuchy, 1434-1485. Freuchy was then, with other lands, erected into a royal barony, and for generations thereafter was the family designation.

This Duncan was succeeded by his grandson, John Grant Younger of Freuchy, who died in l482.

[4] He was succeeded by John, styled the Bard, and who, because of the colour of his hair, was named the Bard Roy. None of the productions of his muse have survived, though, as the name suggests, he must have been possessed of the poetic gift. John the Bard had three sons — John, styled Mór, because of his physical proportions, or his mental gifts, or both. In family transactions he took a prominent part, and is designated in family documents as “filio seniori Johannis Grant de Freuchy” — eldest son of John Grant of Freuchy. His mother was a daughter of Baron Stewart of Kincardine. To this John his father bequeathed the lands of Glenmoriston, and other lands. His second son, by a daughter of Sir James Ogilvy of Deskford, succeeded him as laird of Freuchy; and to his third son he gave the lands of Corrimony in the Braes of Glen Urquhart.

I. John, styled “Mór”, was the first of the Grant Lairds of Glenmoriston. Formerly Glenmoriston was included in the princely [5] dominions of the Macdonalds, Lords of the Isles, and was held of them by Macianruaidh, a vassal chief, and a cadet of those Macdonalds. Annually, at the inn of Aonach, Macianruaidh met the Lord of the Isles on his way to Urquhart and the North, and they exchanged shirts, which ceremony constituted Macianruaidh his “Leine-chriois,” or his firm and fast friend. It amounted to an oath of fidelity. But when King James IV found it necessary to curtail the power of these Insular Potentates, they were deprived of a large portion of their lands, and Urquhart and Glenmoriston were transferred to the Grants of Freuchy for their loyalty to the crown; and thus the lands of Glenmoriston, by his father’s deed, became the possession of his son, John Mór of Tomintouil, where he had his residence in the Glen. The Macdonalds opposed the claims of the Grants, but finding them too powerful, backed as they were by a Royal Charter, they yielded, and transferred their influence to them; and, eventually, Macianruaidh became tutor to Patrick, John Mór’s eldest son. In addition to the [6] lands of Glenmoriston, in 1532 John Mór Grant obtained a Crown Charter of the lands of Culcabock, Cnocantionail, and the Haugh, in the parish of Inverness, formerly the possession of the Hays. In May 1541 he obtained charters of the lands of Carron, Wester Elchies, and Kincardine in Strathspey, for himself and wife in liferent, and for two of his sons in fee.

He married first, Elizabeth, grand-daughter of Sir Robert Innes of that Ilk, and married as his second wife Isabella, daughter of Thomas, fourth Lord Lovat and widow of Allan McRory, chief of Clanranald. This is the local tradition. Others mention her as Agnes, grand-daughter of Lovat.After the death of Clanranald she left Moydart for the Aird, her father’s residence. On her way, she and her retinue camped at Torgyle, in the Braes of Glenmoriston, and sent a message to the laird, then living at Tomantouil, craving his protection. To this request he responded in the most gallant style, and invited her and her party to his residence, where, after a week’s festivities, they were united in the bonds of wedlock. Their children were — [7]

(1) Patrick, who succeeded his father, of whom came the family patronymic of Mac-’ic-Phadruig.

(2) Isabella, who married Grant of Ballindalloch.

(3) John Roy Grant, grandfather of the famous outlaw, Seumas-an-Tuim.

(4) James of Wester Elchies; and

(5) Alexander.

II. Patrick, his eldest son, succeeded his father, John Mór, as Second Laird. His mother by her marriage with Clanranald had one son, who after his father’s death was given in charge to his uncle Lovat. With him he resided during his minority, and got all the educational advantages the times could afford, to qualify him for his future position. Because of his residence in the Aird, this young man was afterwards known by the soubriquet of Ranald Gallda, or Lowland Ranald. He was an accomplished youth, well fitted for the chieftainship. But his bastard brother, John Moydartach, [8] by his talents and tactics, so influenced the clan in his absence, that he was himself elected chief instead of his brother Ranald, the legitimate chief. Lovat, however, espoused his nephew’s cause, and along with the Grants and Mackintoshes, under the leadership of Huntly, then Lord-Lieutenant of the North, an army was despatched to Moydart to overawe the usurper and his followers, and put Ranald Gallda in possession of the chieftainship. In this they were apparently successful, for they met with no opposition. But, as the sequel shows, they were undeceived by-and-by by the tactics of the able and crafty John Moydartach. As the opening of Glenroy, Lord Lovat, accompanied by his nephew, parted with the other clans, and marched homewards by the nearest route down the great Caledonian Valley. This was just what was hoped for by his adversary of Moydart, who unobserved watched his movements from the opposite side of the valley; and at the east end of Lochlochy, on the field of Dalruaridh, Lovat was met by the redoubtable John Moydartach, and a bloody [9] battle was fought, in which Lovat, his eldest son, his nephew Ranald Gallda, and almost the whole of his little army perished. Patrick Og of Glenmoriston and his men fought for his step-brother in this desperate conflict, and was one of the few who escaped uninjured. The origin of the name “Blar-leine” has puzzled historians. Some find it in the circumstance that on account of the great heat, they fought in their shirts. We think it quite as likely that it is derived from the locality in which the battle was fought. Leny is the old name thereof. This battle was fought in July 1544.

Grant of Ballindalloch raised an action at law against Patrick Og of Glenmoriston, on the ground that his father’s marriage with Isabella of Lovat was irregular. In this action he succeeded, and obtained in March 1549 a Crown Charter of his lands, and of which he retained possession for seventeen years. But in 1566, through the influence of his uncle, Lord Lovat, and Campbell of Cawdor, Patrick recovered his rights, and got for himself a new Crown Charter. He was also, in 1569, served heir to his father in the lands of Culcabock. Patric Og of Glenmoriston, with his men, joined (10) Huntly against Queen Mary, and was present with him at the battle of Coirechee, where Huntly was slain, and his army routed by the Queen’s forces, in October 1562. For seven succeeding years Patrick was under Royal displeasure, till remission was granted in 1569, and Culcabock restored.

[10] He married Beatrice Campbell, daughter of Sir Archibald Campbell of Cawdor, and had issue, with other children: (1) John, his successor; (2) Archibald, fined in 1613 for harbouring the outlawed Macgregors. He acted for his brother John at his infeftment in the lands of Kinchurdy in Strathspey, 1621.

III. John, styled Ian Mór a Chaisteil, succeeded as Third Laird. It is traditionally said that when Sir John Campbell of Cawdor visited his father at Inverwick, he found him, his wife, and family dwelling in a primitive residence, styled in Gaelic “tigh caoil,” or a wattled habitation, and that he sent skilled artizans from Inverness to build for them a more commodious dwelling on the site of the present Invermoriston [11] mansion. This more substantial building his son John, the third laird, enlarged and fortified to suit the exigencies of those unsettled times — the reason why he was by the people styled “Ian Mór a Chaisteil”. He was served heir to his father in 1585, and obtained service of the lands of Culcabock in August 1615, the retour affirming that those lands were in the King’s possession during the previous sixty-seven years. The cause of this long alienation is not specified, but we may with probability infer that it must have been for some action offensive to the Government by his father or grandfather during the struggles of those unsettled times, and therefore their restoration must have been to him the reward of loyalty and services to the reigning monarch, James VI. For in 1592 we find him appointed commissioner for the suppression of disorders caused by “broken men,” and arbiter in clan disputes — offices of importance that needed skilful handling, as well as firmness of action in the holder of them.

This Laird was distinguished for his stature, [12] his prowess, and his skill in the use of the sword. When on a visit to King James at Holyrood Palace, he was induced to accept a challenge from one of the champions of those days, who went from place to place parading their strength, and defying the lieges to fight them. This man was so formidable and so invariably successful in his duels, that no one was disposed to accept his challenge. But Laird John soon decided the contest in a rather unique way. One of the preliminaries on those occasions was to shake hands, to shew, we suppose, there was no personal animosity between parties, but so mighty was Laird John’s grasp, that he crushed his opponent’s sword hand as effectually as if it had been caught in a blacksmith’s vice. So, this formidable champion had to confess himself utterly discomfited, without drawing his sword. The incident reminds us of one of the feats of Sir William Wallace, narrated by blind Harry. An English champion offered for a consideration to permit any of the spectators to strike him on the back with a staff he held in his hand, doubtless believing in the strength of his [13] invisible defences, and little knowing how powerless they were against the mighty arm about to wield the staff, and before whose might all his defences gave way, and at one stroke he was laid a helpless object on the scene of his former triumphs.

On this occasion, tradition says it happened that Laird John was rallied anent the primitive lights of his native glen:

| “Gleann-a-mìn-Moireastuinn, | |

| Far nach ith na coin na coinnlean" – |

in allusion to the bog fir candles in common use in the Highlands of those days, even in the best families. The Laird, it is said, laid a wager he could exhibit a Glenmoriston chandelier, with native lights, that would surpass the best and brightest that his metropolitan bantering friends could produce. A messenger was despatched to John Grant — Mac-Eobhainn bhàin — one of the Laird’s most trusted men, and remarkably handsome, to inform him of the circumstances, and citing him to appear in his most picturesque Highland garb with a due [14] supply of the sappiest bog fir that Coiredho could produce. These orders were promptly obeyed. Ian appeared in his best array, a living chandelier, blazing all round with choicest fir torches prepared for the occasion, and thus equipped, he marched into the presence of the arbiters, amid such a galaxy of lights, as completely dimmed the feebler wax. So the Laird, amid the applause and laughter of spectators, at so novel a device, gained his wager. This John Grant — Mac-Eobhainn bhain — was a frequent guest at his master’s table, and an object of jealousy to rivals. It happened at an entertainment at which he was present, that his mistress’ valet – when giving silver spoons to other guests — presented John with a scallop shell from the river Moriston, adding, “So bean dùcha dhutsa Iain, ’s ni i gnothach math gu leòr” – “See, John, you take this shell, a countrywoman of your own, that will serve the purpose sufficiently well.” Insulted as he thought, under the impulse of a momentary resentment he struck the valet. The blow proved fatal, and John, indicted for [15] manslaughter, was immured in the jail of Inverness. During his confinement Lady Glenmoriston chanced to pass in front of the jail with her brother of Freuchy, at one of the windows of which John happened to be at the time, offering to his former patroness his humble salutations as she passed along. The sight kindled old associations, brought back pleasant memories of happy days at Invermoriston, and she exclaimed impromptu:

| “Iain ’ic Eobhainn-bhàin, | |

| Cha bu nar leum d’fháicinn air sluagh | |

| ’S ge do mharbh thu Adam crion, | |

| ’S mór an diohhail thu bhi’uam.” |

Her wishes for the restoration of her favourite were granted. Her brother, who was Sheriff of the county, shortened John’s term of imprisonment; and to his joy, and that of his mistress, he was once more in his place and position in her service.

This Laird had a wadset of the forest of Cluany, and of the lands of Borlum and Balmacaan in Glen-Urquhart. Grant of Freuchy gave him also the appointment of Chamberlain [16] of the lordship of Urquhart. In 1621 he purchased the lands of Kinchurdie in Strathspey for his second son, John.

He married Elizabeth, daughter of the Laird of Grant, who survived him. He died in 1637, leaving issue:

(1) Patrick, who succeeded him.

(2) John, who in 1648 was appointed Chamberlain of the Lordship of Urquhart, in room of his deceased father. From him descended the Grants of Crasky. His son Duncan was alive in 1702.

(3) Duncan of Aonach, who with his wife, Catherine Macdonald of Glengarry, had a wadset of the lands of Dundregan. From him are descended the Grants of Dundregan. He died in 1637, shortly after his father.

IV. Patrick, eldest son of John Mór a Chaisteil, succeeded as Fourth Laird. He appears as witness in Grant documents, from 1603 onwards, as “apparent of Glenmoriston, and eldest lawful son of John Grant of Glenmoriston”. [17] In March 1637 he was served heir to his father in the lands of Culcabock. In 1640 he joined the laird of Freuchy in giving assurances for the good behaviour of his relative, James Grant of Carron, alias Seumas-an-Tuim, the notorious freebooter. The wild career of this man had its origin in accident. Unintentionally he occasioned the death of his own cousin, a son of Grant of Balindalloch. Believing that he aided Seumas-an-Tuim, the Grants of Balindalloch in retaliation slew John, the brother of James. Therefore, Seumas an-Tuim, in December 1630, burned Balindalloch’s cornyard, stables, byres, and barns, and drove away as many of his cattle as escaped the flames. The Balindallochs sought the protection of the Earl of Murray, who employed a party of “broken Macgregors” to capture James, and succeeded in taking him in a house in Strathavon after a desparate fight, in which nearly all his men were killed, and he himself severely wounded. When sufficiently recovered, he was despatched under a strong escort to Edinburgh Castle, “being,” [18] says Spalding in his quaint manner, “admired, and looked upon as a man of great vassalage.” Here he remained prisoner for the space of two years, till his wife contrived to send him rope in a cask of butter, by means of which he escaped through his prison window. This was in October 1632. Once more at liberty he renewed his attacks on his enemy Balindalloch, who retaliated by again employing “the broken” Macgregors, under their famous leader, Patrick Dubh Geir, a Glenlyon man. James, however, succeeded in eluding their toils, and with a company of his men came by night to Balindalloch’s house, and sent him a message that a friend wished to speak to him. Soon as Balindalloch appeared, James and his men seized him, and wrapping him in their plaids, bore him away to the neighbourhood of Elgin, to one of James’ haunts, where he was confined for the space of three weeks in a broken-down kiln, where he almost perished for want of food. He contrived, however to make his escape by bribing one of his keepers, and soon as he was at large [19] hired one Thomas Grant of Speyside to take James, dead or alive. On being informed that he had undertaken this mission, James and his men went immediately to his residence and killed or drove away sixteen of his cattle, and finding himself shortly afterwards in the house of a friend, dragged him naked out of his bed, and despatched him with many wounds.

While heartily disapproving of the violent proceedings of James-an-Tuim, the Frasers of Lovat, the Grants of Freuchy, and the Grants of Glenmoriston — his relatives — equally disapproved of Balindalloch’s unrelenting persecution of him. So Patrick of Glenmoriston, with other friends, agreed to give assurances to Government of the future good behaviour of James, on the understanding that on both sides this feud should cease. These conditions Balindalloch accepted, glad no doubt to be relieved of so capable and dangerous a foe as James-an-Tuim showed himself to be. This man, in many ways remarkable, after wards took part in the wars of the Commonwealth, [20] joined the winning side, got remission of all his past misdeeds, and died in his bed, the hero of story and song. The following is the chorus of one of the songs

| A mhnathan a ghlinne, | |

| A mhnathan a ghlinne, | |

| A mhnathan a ghlinne, | |

| Nach mithich dhuibh eiridh, | |

| ’Us Scumas an Tuim a’g iomain na spréidhe. |

Patrick, the fourth laird, married a daughter of Fraser of Culbockie, and had issue, besides other children:

(1) John, who succeeded him, and

(2) Lilias, who married Alexander Grant of Sheuglie, Esquire.

This Laird died in 1643.

V. John Grant, eldest son of the preceding Laird, succeeded in March 1643. In 1644 he appears in the Valuation Roll of the county of Inverness as “apparent of Glenmoriston,” which seems to imply that he was under age at the time of his father’s death. His lands were valued at £574, 15s. Scots.

[21] In 1684 there was a keen litigation between this laird and his relative, Grant of Freuchy, anent the redemption of Balmacaan in Glen Urquhart, of which, up till this period, the Grants of Glenmoriston had a wadset. In March 1687 an instrument of ejection was issued by the Court, so that the litigation must have been a protracted one. In April of this same year, this laird entered into an engagement with James Grant of Dalvey, advocate, offering an annual payment for the prosecution of his suit against Grant of Freuchy. As he had to borrow largely to defray those law expenses, he gave Lord Lovat, one of his creditors, a wadset of Dalcataig, and other lands extending up the south side of the River Moriston as far as Inverwick. Unable to redeem those lands within the specified time, they became the permanent property of Lovat. This laird, from the colour of his hair, was known by the soubriquet of Ian Dónn, or “John the brown haired.” He married a daughter of Fraser of Struy, and died in 1703, leaving issue: [22]

(1) John, who succeeded him, styled Ian a-Chragain.

(2) Alexander, styled of Blarie.

(3) Patrick, and other children.

IV. John, eldest son of the preceding, succeeded on the death of his father. In an agreement between the latter and James Grant of Dalvey, advocate, dated December 1687, he is styled “John Grant, younger of Glenmoriston.” On the 21st December 1695 he and his brother Alexander of Blarie entered into a bond with Murdoch Macleod for £500 merks Scots. On the 23rd of June 1703 he was entered as heir to his late father, John Grant of Glenmoriston. On the 9th of March 1714 he was entered as heir to other ancestors. While yet a minor, he and his men took part in the battle of Killicrankie — Raonruaridh, as the Highlanders name it. Alastair Dubh of Glengarry, John Grant, younger of Glenmoriston, and his father’s chamberlain, Alexander Grant — “Alastair Dubh mac Dhunchaidh mhóir” — [23] were reckoned the strongest and bravest warriors of all that fought on that memorable field. They stood side by side in the conflict — the Glengarry and Glenmoriston men usually went together in those Jacobite wars — and it was noticed that for years after, their path of fight could be traced by the luxuriant grass that grew over the graves of the multitudes that fell beneath their weapons. The shield and sword with which Ian-a-Chragain fought on this memorable occasion are still preserved at Invermoriston House. The following romantic incident connected with the Raonruaridh affair has been traditionally transmitted. Alastair Dubh, the Glenmoriston Chamberlain, on his way home late that same day, entered a cottage in the Braes of Athole, and pleaded for a night’s shelter. The mistress of the cottage declined his request, giving as her excuse for want of Highland hospitality, that her husband was from home, and, moreover, that he forbade her harbouring strangers in such unsettled times. Alastair replied he only craved shelter for the night, and that he would have it, or a stronger [24] than he would expel him. By and by her husband arrived. She narrated her conversation with the stranger, and his reply. So the two get into grips — the Athole man to expel Alister, and the latter determined not to be expelled. The struggle was a long one, but eventually the Athole man had the victory. Step by step, in spite of vigorous resistance, he drove his weary, way-worn, battle-worn opponent to the door, who in his desperation laid hold of the pot chain that was suspended over the hearth, yet he dragged him out, chain and all, and laid him on his back on the green sward at his door, adding, “I did not believe any man could have so tried me. You are welcome to such hospitalities as my house can afford; and this chain you have in hand you will bring with you as a gift from me, to testify to your prowess.” This veritable chain, not many years ago, was doing duty in the house of a poor crofter near Invergarry House. The Lairds of Glengarry and Glenmoriston having a case of disputed boundaries, agreed to have it decided in the following novel way, namely, that each [25] should choose his champion, both of them to be led to the disputed ground, there to wrestle for the mastery; and that where either pushed the other till he fell exhausted, that spot should be fixed upon as the boundary line between the Lairds. Alister was the victorious champion, and it is alleged he used up a pair of new Highland brogues that day. So the dispute was decided.

Ian-a-Chragain was present at the skirmish of Cromdale, where the Highlanders, under General Buchan, were defeated. He also took part in the rebellion of 1715, under the Earl of Mar. He was present also at the battle of Sheriffmuir, where he fought by the side of his old companion in arms, Alister Dubh, the Glengarry Chief, whose life he was the means of saving on that occasion. Alister, now an old man, wore trewis tied round the waist with a belt or thong, which unhappily gave way in the heat of a personal encounter with an English trooper. Impeded, as the old hero was, with his fallen trewis, he would have been vanquished but for the timely aid of his valorous friend, the Chief of Glenmoriston.

[26] For the part he took in those actions, the Glenmoriston estates were sequestrated, and remained Crown property till 1732, when they were sold by auction, and purchased by Sir Ludovic Colquhoun of Luss, advocate, afterwards Sir Ludovic Grant of Grant, for £1200. Through the good offices of Sir Ludovic, they were subsequently restored to the family.

Ian-a-Chragain was twice married: first to a daughter of Baillie of Dunean, who survived only a year; she died in child-bed. His second wife was one of the eleven daughters of the celebrated Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel — Ni-mhic-Dhomhail Duibh. This lady survived her husband, and died in 1759 at the advanced age of eighty years. At the time of her death, she left behind her no fewer than two hundred descendants. The following obituary notice is from the Scots Magazine of that year: "Died at Invermoriston, in the eightieth year of her age, Janet Cameron, daughter of Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel, and relict of John Grant of Glenmoriston, Esquire, to whom she bore ten sons and five daughters. By these, who were all [27] married, there were about two hundred persons descended of her own body, most of whom were present at her funeral. Her corpse was carried to the churchyard by her children, grand children, great-grand-children, and great-great-grandchildren” — a rare circumstance, and, as far as we know, unique in the history of Highland families. Those of the family of this Laird of whom there is record are:

(1) John, who succeeded his father.

(2) Patrick, who succeeded on the decease of his brother John.

(3) Duncan, styled “Corneilear,” married a daughter of Grant of Corrimony, by whom he had a son, who died in India, and three daughters married respectively to Donald Macdonald of Livisy, Macintosh of Lewiston, and Maclean.

(4) Allan, commonly known as Ailean Mac-’ic-Phadruig, a notable warrior. He took part in the rebellion of 1745, fought several duels, and latterly lived in the Aird, where he died.

(5) Isabella, who in 1713 married Alexander Grant of Sheuglie, Esquire. She was the

[28]

mother of Colonel Hugh Grant of Moy, who served in the Indian army, bought that estate, and at his death bequeathed it to his relative, James Murray Grant, Esquire, whose descendants are still in possession of it.

VII. John Grant, eldest son of the preceding, succeeded him as Seventh Laird. In May 1733 he had part of his father’s forfeited estate restored to him, through Sir Ludovic Colquhoun of Luss. In 1734 he got a Crown Charter of those lands, and subsequently, by an arrangement between himself, the Laird of Grant, and his brother Patrick, he recovered possession of all his lands. He possessed only for a year and six months, and died in December 1734.

VIII. John was succeeded by his brother Patrick as Eighth Laird, from the colour of his hair known by the name of “Patrick Buidhe.” In 1735 this Laird entered into a [29] bond of manrent with John Macdonell of Glengarry, for purposes of co-operation and mutual protection. He took no part personally in the “rising” of 1745; but his men did, and along with the Glengarry men, under the leadership of Angus Og, their chief, they were present in all the engagements of that campaign, save the battle of Culloden. They were, however, on their way to that field, when they met the discomfited fugitives on the moor of Caipleach. We believe, however, that while he abstained from taking an active part personally in the enterprise, he secretly wished it success. But considering the uncertainty of the issue, and what his fathers had suffered in the cause of the Stuarts, neutrality on his part was a wise course. But all the same, the fact that his men “were out,” subjected the inhabitants of the Glen to the signal vengeance of the Duke of Cumberland. A party under Major Lockhart entered it, and committed acts of inexcusable barbarity even on unoffending individuals. Two old men, and the son of one of them, were shot as they were quietly working in a field, and [30] anticipating no danger. Lockhart ordered Grant of Dundreggan to be stripped naked, and carried to a gallows, from which he had the bodies of the other three men suspended by the feet. He would have hanged Dundreggan, but for the interposition of Captain Grant, of Lord Loudon’s regiment. They took her gold rings off his wife’s fingers in the rudest manner, and threatened to cut off those that somewhat stiffly resisted this stripping operation. Their house was burnt to the ground after the soldiers had looted it and taken possession of such valuables as could be conveniently borne away. About seventy men were induced by specious promises to appear at Inverness, and deliver up their arms. On doing this they were to have full remission for the past and protection for the future. On the faith of these promises they submitted, several of whom took no part in the rebellion. But instead of either remission or protection they were shipped to West Indian plantations, whence only two of them ever returned to tell the tale of their woe! Influenced by the instinct of self-preservation, [31] some of their companions who were left behind banded together for self-protection, and bound themselves by an oath, never to deliver up their arms — and should they be assailed, to fight to the death for each other. These were Patrick Grant of Crasky, John Macdonell, Alexander Macdonell, Alexander, Donald, and Hugh Chisholm, and Charles Macgregor. They were subsequently joined by Hugh Macmillan, who also took their oath. During summer and autumn, after the battle of Culloden, they lived in seclusion among the mountains, save that they paid occasional visits to ascertain how it fared with their families, and in case of danger to defend them. Part of the work they prescribed for themselves, was to harass the military that scoured the glen; to recover the people’s cattle which they drove away overawe, and make the soldiers uneasy by every means in their power; and so effectually did their tactics succeed, that the glen was soon exempt from spoliations and barbarities, such as we gave specimens of. Moreover, but for their presence of mind and loyalty, it is [32] almost certain, as the sequel shows, that Charles Edward, would at this time have fallen into the hands of his pursuers. About the end of July 1746, Charles, who was in the greatest extremity, was put in charge of these men by Macdonald of Glenaladale, as young Clanranald. But they recognised him at once, notwithstanding the miserable plight he was in — his shirt yellow as saffron, his raiment in tatters, and his shoes quite worn. But his miseries only endeared him to them all the more, and he was received by them with every demonstration of loyalty and veneration. To them he was their prince, be his raiment and other accidentals what they may. At once they constituted themselves his bodyguard, assured Glenaladale they would provide for him, and defend him till more propitious times arrived.

Meantime they marched together to their cavern in the unfrequented wilds of Coiredho — a cave since known as Uaimh’-Phrionns’, in remembrance of Charles’ sojourn there. A reward of £30,000 was offered by the Government (33) of that day, to any one who would deliver Charles into their hands. Yet the poorest of them scorned the idea. Sir Alexander Boswell of Auchinleck commemorates this in his poem on the fidelity of the Highlanders in the Rebellion of 1745-6 — “Exulting, we’ll think on Glenmoriston’s cave.” [33] The following oath was imposed upon them by their Royal visitor, namely, “That all the curses the Scriptures pronounced might fall upon them and their posterity, if they were not faithful to him in greatest dangers, or disclose to man, woman, or child that he was in their keeping, till once he was out of all danger.” So well did these true men keep their oath, that not one of them even spoke of his being with them till twelve months after he had sailed to France. Charles told them “they were the first Privy Council he had sworn since the battle of Culloden; and that he would not forget them if ever he came to his own.” Here, he remained with these men from the end of July till the end of August 1746. On the 20th of that month, the way being found safe, the party left Coiredho, crossed the valley of the Moriston and the

[34] Glengarry hills to the neighbourhood of Achnacarry, where they arrived on the 20th, and met Cameron of Clunes, who conducted the Prince and Lochiel to Benalder, where they were joined by Cluny, also in hiding. Here the whole party remained till the month of September, when they embarked for France, from the very locality at which the unfortunate Prince landed, about a year previously, with such high hopes. Such was the end of this romantic, may we not say quixotic, expedition. And yet, had it been guided with more skill at a certain stage of it, ‘tis hard to say what the result might have been. It is melancholy to think that Charles, on whom such wealth of loyalty, service, and affection was lavished, showed himself so unworthy of it by his want of self-respect in after years. These Glenmoriston men, after his departure, remained for some time longer in arms against the Government, and then settled down to the ordinary occupations of life. Hugh Chisholm survived till 1812, and to the last would not give any one his right hand — “that hand,” as [35] he used to say, “having been honoured with the royal grasp on parting with his Prince.” Patrick, the Eighth laird, married a daughter of John Grant of Crasky, Esquire, descended from John, the Second Laird. This lady, from the auburn colour of her hair, was known among the people as “a ‘Bhaintighearna-ruadh.” They lived at Inverwick, where he died in March 1786, in the eighty-sixth year of his age. Their children are:

(1) Patrick, who succeeded him.

(2) Alexander, a Lieutenant in one of the Highland regiments raised by Government for service in Canada. He was a member of the executive and legislative council of Upper Canada, and for nearly fifty years Commodore of the fleet on Lake Erie. He died in May 1813, in the eighty-first year of his age, at Grosspoint, near Detroit.

(3) Allan, a Lieutenant in his Majesty’s service. His only daughter married Captain Duncan Macdonell of Aonach, whose only son, a promising medical officer, died in India. One of the two newspapers that came to the

[36]

Glen in those days came to Captain Allan. It was a monthly publication. When the Captain had perused it, Mr William Sinclair, the schoolmaster, got it, and rendered the contents, advertisements, and all, into Gaelic to a large and appreciative audience, convened by public intimation given in the school — "tempora mutantur.” Captain Allan Grant died at Inverwick at an advanced age.

(4) Alpin, a major in his Majesty’s service. Latterly he lived at Borlum, in Glen Urquhart. His only son died in India. His daughters were married respectively to Grant of Dalshangie, Fraser of Tor, and Mr Alexander Grant, afterwards factor on the Glenmoriston estates.

IX. Patrick, eldest son of the preceding, succeeded as Ninth Laird. This Laird possessed great physical strength. Riding home late at night along the Fort-Augustus road, he found the gate of the bridge that spans the river closed, and having failed to rouse the sleepy toll-keeper, he laid hold of it, and [37] by main force wrenched it off its hinges, and threw it over the parapet into the river, to the bewilderment of the keeper, who next morning found it unaccountably gone. It was a heavy iron gates and firmly fixed. In June 1757, during the lifetime of his father, he married Henrietta, daughter of Grant of Rothiemurchus, “a Bhaintighearna-bhreac.” At his marriage, his father “disponed his estate to himself in life-rent, and to his son in fee.” In 1773 a similar disposition was made in his favour. Then all the old attainders for rebellion had been removed, and in March 1774 he obtained a Crown Charter, confirming him in full possession of all the forfeited lands. It was Laird Patrick’s almost daily habit to sit for hours in the inn of Aultgaibhnec, near his mansion, and listen to the gossip of travellers, whom he courteously received and entertained with generous libations of “mountain dew.” Nor is the reader to suppose that he lost respect by so mingling with the common people. It was a green spot in their memories that they had broken bread with him, drank his health, and [38] were permitted to ventilate their opinions on sundry subjects in the presence of the “Tighearna” himself. Nor was there danger of rudeness or incivility of any sort. His social position forbade it, and, what was of as much weight in the eyes of a Highlander of those days, his stately physical proportions warned them, the Laird was a match for any half-dozen of them. He departed this life in December 1793. His children are:

(1) John, who succeeded him.

(2) James, W.S., and one of the curators of his brother’s sons, and father of the late Patrick Grant, Sheriff-Clerk of Inverness-shire.

(3) Patrick, who died in America.

(4) William, appointed one of the curators of his brother’s children. He died at Berhampore in October 1808, in the thirty-seventh year of his age. He bequeathed £5300 for carrying on evangelistic work in India, besides several generous legacies to his relatives at home.

(5) Ellen, who married Ewen Cameron of Glenevis, Esquire.

[39]

(6) Elizabeth, who married Simon Fraser of Foyers, Esquire.

(7) Jane, who, in 1781, married Charles Mackenzie of Kilcoy, Esquire; and

(8) Grace, who married Colin Matheson of Bennetsfield, Esquire.

X. John, his eldest son, succeeded on the death of his father as Tenth Laird. He was served heir on the 27th of February 1795, and married previous to 1789 Elizabeth Townsend, daughter of John Grant, Commissary of Ordnance, New York, and a cadet of the Grants of Freuchy. In 1780 he joined the 42nd Regiment with a captain’s commission. He landed in Bombay in 1782, shared the toils and dangers of the war with Tippoo, and stood the siege of Mangalore in 1790. On his return home he was appointed Major in the Strathspey Fencibles, and died in 1801 at Invermoriston, with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. In those days, compared with more modern times, physicians were few and far between; [40] and Donald Corbet, an old soldier, walked to Edinburgh for medicines for Colonel Grant in his last illness, and was back to Invermoriston the third day; and considering the distance, this was reckoned a rare feat of pedestrianism, even in those days of vigorous walking. Mrs. Grant died at Inverness on the 3rd of April 1814. Colonel Grant’s children are:

(1) Patrick, who succeeded him.

(2) James, who succeeded his brother Patrick.

(3) Henrietta, who married Thomas Fraser of Balnain, Esquire; and

(4) Ann, who was married to Roderick Mackenzie of Flowerburn, Esquire.

XI. Patrick Grant succeeded his father as Eleventh Laird. He delivered his father’s testament on the 9th of October 1801. On the 3rd of May 1802 he was returned heir to his father, and obtained infeftment in his estates. He died at Foyers, the seat of his uncle and aunt, in September 1808, in [41] consequence of a fall from a tree when gathering fruit. He died unmarried.

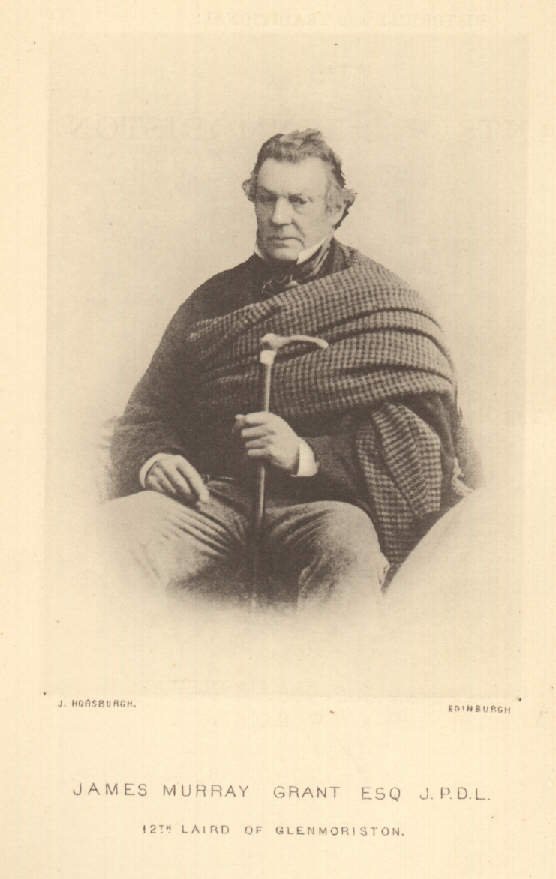

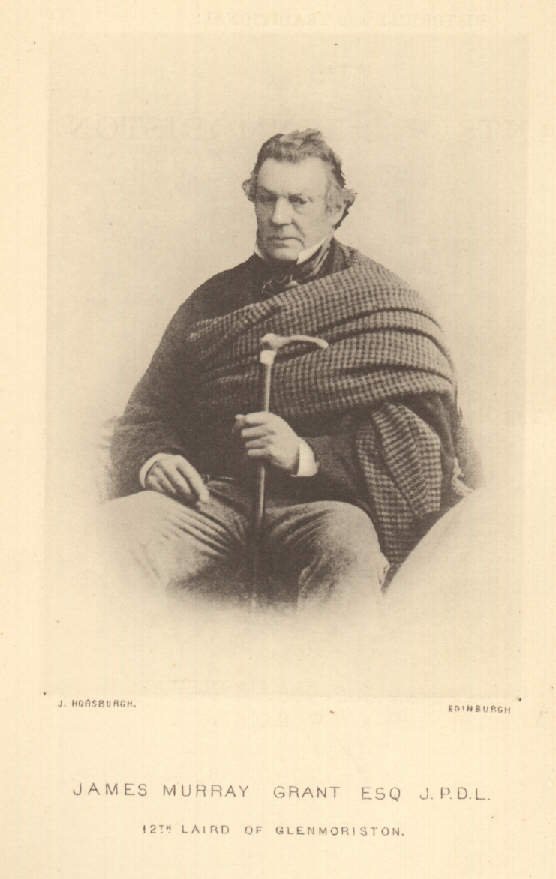

XII. James Murray Grant, J.P., D.L., succeeded on the death of his brother as Twelfth Laird. On the 15th May 1809 he was returned heir general to his grandfather Patrick, and on the 30th of the same month, heir special to his elder brother Patrick, whereupon he was infeft in the estates. In October 1814 he also executed a precept of “clare constat” for his own infeftment as heir of his grand father Patrick in certain portions of the Barony of Glenmoriston, and was infeft on the same day. He acquired the lands of Culbin, Kintessack, and Moy, as the heir of tailzie and provision to Colonel Hugh Grant of Moy, to whom he was returned heir general on the 2nd of June 1822; and on the 6th of July following he obtained a Crown Charter of these lands. In 1824 he acquired the lands of Earnhills and others from Captain Gregory Grant. He also purchased the lands of [42] Knockie, Foyerbeg and others. He died at Inverness, 8th August 1868. In October 1813 he married Henrietta, daughter of Ewen Cameron of Glenevis, Esquire, who survived him, and died in June 1871. He left issue:

(1) John, Captain in the 42nd Royal Highlanders.

(2) Ewen, Colonel in the Indian army. He married the eldest daughter of Colonel Pears of the Madras Artillery; with issue, a son and four daughters.

(3) Patrick, E. I. Civil Service. He married Elizabeth, second daughter of Donald Charles Cameron of Baracaldine, Esquire; with issue, two Sons and four daughters.

(4) Hugh, Lieutenant-Colonel in the Indian army. He married an Indian lady; with issue, a son and daughter.

(5) James Murray Grant, Major-General in the Indian army. He married Helen, third daughter of Donald Charles Cameron of Baracaldine, Esquire; with issue, four sons and three daughters.

(6) Jane, married to William Unwin, Esq., of the Colonial Office; with issue.

[43]

(7) Elizabeth, married Alexander Pierson of the Guynd, Forfarshire, Esquire.

(8) Helen.

(9) Harriet, married Frank Morrison of Hole Park, Kent, Esquire.

(10) Isabella.

XIII. John Grant, eldest son of the preceding, would, had he survived, been Thirteenth Laird. He was Captain in the 42nd Royal Highlanders — an Reisemeid dubh. In 1850 he married Emily, daughter of James Morrison of Basildon Park, Berks, Esquire. After her death he married Anne, daughter of Robert Chadwick of High Bank, Prestwick, county of Lancaster, Esquire. He died at Moy House, Forres, on the 17th August 1867. He left issue:

(1) Ian Robert James Murray Grant, born in 1860.

(2) Ewen, born 1861.

(3) Heathcote Salisbury, born in 1864.

(4) Frank Morrison Seafield, born 1865.

[44]

(5) Emily, married Major Astell of the 60th Rifles; with issue, a son and daughter.

Captain Grant predeceased his father. He died at Moy House, Morayshire, in August 1867.

XIV . Ian Robert James Murray Grant, born in 1860, succeeded his grandfather as Fourteenth Laird in 1868. He is a Lieutenant in the first battalion of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders — Reisemeid Ailean nan Earrachd. He married, in February 1887, Ada Sophy Ethel, daughter of the late Colonel Davidson, C.B.. Colonel Davidson was well known during the Mutiny, as Resident of Hyderabad in the Deccan, which, at that time, was one of the most important posts in India.

[45] Selections from the Lyrics, Songs, and Elegies of Glenmoriston Bards.

WHEN Highland literature was almost all oral, the Bard occupied an important place. He was the Chief’s family historian, as well as Bard. By him, traditionally, as well as in verse, clan history was transmitted. Therefore to the songs and the narratives of the Bards we owe much of the knowledge we have of the past history of the Highlands and Highland clans. In some instances the Bardic office was hereditary, but, according to Horace, as the poetic gift is not so, the office of Seanchie or family historian, was generally joined to it. So when the Bardic gift may have disappeared in any one of the successive links of the [46] official chain, the want was supplied by the Seanchie, and thus a continuity was preserved, both of a class, as well as of song and narrative.

The Bards, of whose productions we give specimens in the following pages, are to be ranked, rather among amateur devotees of the Celtic muse. And though we do not wish to exaggerate the merits of their Bardic productions, we do claim, that among poets of their class, they occupy a position of considerable merit. We find in the social fabric, different grades of men, differing educationally as well as intellectually and socially; so there have been along the ages, poets that have addressed themselves to such respectively; and Bards, such as the following, who though they do not profess to soar to the highest regions of poetry, yet claim their own place, and also fill their place as homely warblers, with gifts as enabled them to express their sentiments skilfully, suitably, and attractively, so as to interest and educate the circle to which they belonged.

[47] The first of them with the reputation of being a good poet is John Grant — Mac-Eobhainn Bhain already noticed. He lived in the times of John, the Third Laird. Several of his compositions, now lost, could be recited by people who have passed away within recent years; and which shews that the productions of his muse had merit, seeing they survived so long in the memory of his fellow countrymen. We can only give the following stanzas of one of them, an elegy on the death of his patron.

| Fhir mhóir bu mhath cumadh, | |

| Thug thu bar air gach duine. | |

| ’Righ bu shàr mhath, an curaidh measg sluaigh thu. | |

| Fhir mhóir bu mhath cumadh, &c. | |

| Le d’ thargaid, ’s do claidheamh, | |

| Air do shliosaid na laidhidh. | |

| Mar ri bogha nan saighead bu chruaidhe. | |

| Le d’ thargaid, &c. | |

| ’Nuair a dheanadh tu ghlacadh, | |

| Rachadh direach mar dhearcadh. | |

| Nàile bhristeadh e chairt air am buaileadh. | |

| ‘Nuair a dheanadh tu, &c. |

[48] The next that deserves mention is Archibald Grant — Gilleasbuig an Tombhealluidh — nearly related to the Glenmoriston family. None of his productions have survived, save a few fragments, and these because of his connection as tutor with Angus Òg of Glengarry, whom his father had put in Grant’s charge. Grant’s mother was a sister of Julia of Keppoch — Sile-ni-mhic-Raonuill — a poetess reckoned not much inferior to her relative John Lòm. It is said he never took the boy in his arms but he accompanied the embrace with an expression in verse of his affection for the young Chief. The following stanzas are apparently a part of a morning lullaby:

I |

Bobadh ’us m’ ànnsachd, | |

|---|---|---|

| Gaol beag agus m’ ànnsachd. | ||

| Bobadh ’us m’ ànnsachd | ||

| Moch an diugh hò! | ||

II |

Bithidh Aonghas a Ghlinne | |

| Air a chinneadh na cheannard. | ||

| M’ ullaidh ’us m’ ànnsachd | ||

| Moch an diugh ho! | ||

III |

[49] Bheir sinn greis san T6mbhealluidh, | |

| Air aran ’us àmhlan. | ||

| M’ ullaidh ’us m’ ànnsachd | ||

| Moch an diugh ho! | ||

| Again, in recognition of his prospective chieftainship and chieftain possessions, he sings: | ||

| Ho! fearan, hi! fearan, | ||

| Ho! fearan ’s tu th’ ann. | ||

| Aonghais òig Ghlinnegaraidh | ||

| ’S rioghail fearail do dhréam. | ||

I |

Gu’m bheil fraoch ort mar shuaimhneas, | |

| Dhut bu dual chur ri crànn. | ||

| Ho! fearan, hi! fearan, &c. | ||

II |

’S leat islean ’s leat uaislean, | |

| ’S leat uaich gu da cheann. | ||

| Ho! fearan, hi! fearan, &c. | ||

III |

’S leat sid ’us Dailchaorainn, | |

| ’S Coirefraoich nan damh seang. | ||

| Ho! fearan, hi! fearan, &c. | ||

IV |

’S leat Cnodairt a bharraich, | |

| ’Us a fearann gu cheann. | ||

| Ho! fearan, hi! fearan, &c. |

[50]

In further celebration of the chieftainship, and chieftain accomplishments of his beloved Angus, he sings:

I |

Mo ghaol, mo ghaol, mo ghaol an giullan. | |

|---|---|---|

| Mo ghaol ’s mo luaidh, fear ruadh nan duine. | ||

| Cas dhireadh nan stùchd, ’o d’ ghlùn gu d’ uilinn, | ||

Lamh thaghadh nan àrm ’sa shealg a mhonaidh. |

||

II |

’O Chluanaidh an fheòir, gu sroin Glaic-chuilinn, |

|

| ’Us Maolchinn dearg, gu ceann na Sgurra. | ||

| ’Nuair theid thu do ’n fhrìth le strith do chuilean, |

The following fragment is part of a congratulatory address to the young Chief on his getting a new Highland dress:

| Theid an t-éideadh theid an t-éideadh | |

| Theid an t-éideadh air a ghille, | |

| Theid an t-éideadh crios ’us féileadh, | |

| Theid an t-éideadh air a ghille | |

| ’S cha cheil mi ’o dhuine tha beò, | |

| Mo ghaol do Aonghas Og a Ghlinne. |

When Angus Og left Tombealluidh for his ancestral residence at Cragan-an-fhithich, he [51] was accompanied by his affectionate friend, with a gift of twenty cows and a bull — “buaile bhò”. This Angus Og is the Glengarry Chief who with his men joined the forces of Prince Charles Edward in 1745, and was killed by the random shot of one of the Highland soldiers, when cleaning his gun after the victory at Falkirk.

John Grant — Iain-mac-’illeasbuig — was the son of Archibald last mentioned, and reckoned by his contemporaries a poet of merit. About the year 1772 he joined the army, where he attained the rank of sergeant, and after serving his time, retired to his native glen with a pension. Besides other campaigns, Grant took part in the memorable siege of Gibraltar, and distinguished himself by many acts of gallantry. During the heat of the siege, the range of the only Well, out of which the detachment to which he belonged could draw water was so accurately known to the enemy, that none could venture upon the experiment without endangering life. But Grant, after taking accurate note of the intervals of firing, [52] dared bravely to rush to the spot, and succeeded in bringing the necessary supplies, to the admiration of his fellow soldiers.

Only two of the productions of his muse remain, the first of them an energetic attack upon the system of large farms at the expense of the smaller tenantry. He lauds Colonel Grant’s appreciation of his men; maintaining that, had he lived, they would not be banished to make way for sheep, which he thinks highly impolitic. He resolves to accompany the emigrants to the land of their adoption, and concludes with a prayer to the Almighty that He would bring them safely to their destination. Grant, however, did not emigrate. The second of his remaining productions is a sacred song, composed on his deathbed, full of pious sentiment, as well as knowledge of the sacred Scriptures, and, we believe, the last of his compositions.

[53]

THE SHEEP SONG: ORAN NAN CAORACH-MHORA.

I |

Deoch slàinte ’Choirneil nach maireann, | |

|---|---|---|

| ’S e chumadh seòl air a ghabhail. | ||

| Na’m biodh esan os ar cionn | ||

| Cha bhiodh na crionn air na sparran. | ||

II |

Bhiodh an Tuath air an giullachd, | |

| ’S cha bhiodh gluasad air duine. | ||

| ’S cha bhiodh àrdan gun uaisl’, | ||

| Faighinn buaidh air a chummant’. | ||

III |

Tha gach Uachdaran fearainn, | |

’S an Taobh-tuadh air a mhealladh. |

||

| ’Bhi cuir cùl ri ’n cuid daoin’, | ||

| Airson caoraich na tearra. | ||

IV |

Bha sinn uair ’s bha sinn miobhail, | |

| ’N uair bha Frangaich cho lionmhor, | ||

| Ach ged’ thigeadh iad an raoir, | ||

| Cha do thoill sibh dhol sios leibh. | ||

V |

Na’m biodh aon rud ri tharruing | |

| Bhiodh mo dhùil ri dhol thairis, | ||

| [54]’On dh’ fhalbh muinntir mo dhùthch’, | ||

| ’S beag mo shunnd ris a ghabhail. | ||

VI |

Bith’ mi falbh ’us cha stad mi, | |

| ’S bith’ mi triusadh mo bhagaist. | ||

| ’S bith mi comhladh ri càch, | ||

Nach dean m’ fhagail air cladach. |

||

VII |

Ach a Righ air a chathair, | |

| Tha na d’ Bhuachaill’ ’s na d’ Athair. | ||

| Bith na d’ fhasgaidh do ’n tréud | ||

| Chaidh air reubadh na mara. | ||

VIII |

’Us a Chriosd anns na Flaitheis, | |

| Glac a stiùir ’na do lamhan. | ||

| Agus réitich an cuan, | ||

| Gus an sluagh leigeil thairis. |

JOHN GRANT’S SACRED SONG: LAOIDH IAIN-’IC-ILLEASBUIG.

I |

Gu’r a mise tha truagh dheth, | |

|---|---|---|

| Air an uair s’ tha mi cràiteach. | ||

| ’S cha ’n e nitheanan saoghalt’, | ||

| Adh’ fhaodas mo thearnadh. | ||

| [55] No ’s urrainn mo leigheas | ||

| Ach an Lighich’ is Airde. | ||

| Oir ’s E rinn ’ar ceannach, | ||

| Chum ar n-anam a thearnadh. | ||

II |

Gu ’ar tearnadh ’o chunnart, | |

| Do dh’ fhuiling ar Slan’ear. | ||

| Air sgath a shluaigh uile, | ||

| Gu an cumail bho’ ’n namhad. | ||

| Do thriall ’o uchd Athair, | ||

| Gus an gath thoirt ’o ’n bhàs dhuinn. | ||

| ’N uair a riaraich E ceartas, | ||

Air seachduinn ma caisge. |

||

III |

Air Seachduinn ma Caisge, | |

| Chaidh ’ar Slàn’ear a chéusadh. | ||

| Sa chur ri crann dìreach | ||

| Gu ’chorp prìseil a réubadh. | ||

| Chuir iad àlach ’na chasan, | ||

| ’S na bhasan le chéile, | ||

| ’Us an t-sleagh ann ma chliabhaich, | ||

’Ga riabadh le géir-ghath. |

||

IV |

Sud an sluagh bha gun tròcair, |

|

| ’Gun eòlas gun aithne. | ||

| Mac Dhé ’bhi ’san t-seòls’ ac’, | ||

| ’S aid a spòrs’ air ’sa fanaid. | ||

| [56] Dara Pearsa na Trianaid | ||

| ’Chruthaich grian agus geallach: | ||

| Dhoirt E fhuil airson siochaint, | ||

| Gu siorruidh do’r n-anam’. | ||

V |

Ann an laithean ’ar n-òige | |

| Bha sinn gòrach ’san àm sin, | ||

| A caitheamh ’ar n-ùine, | ||

| Gun ùrnuigh gun chrabhadh. | ||

| Ach cia mar ’s urrainn dhuinn duil, | ||

| ’Bhi ri rùm ann am Fàrras, | ||

| Mar treig sinn am peacadh | ||

| Tre chreideamh ’san t-Slàn’ear. | ||

VI |

Tha na’r peacaidh cho lionmhor, | |

| Ris an t-siol tha ’s an àiteach. | ||

| Ann an smuain ann an gniomh’ran, | ||

| ’N uair a leughar na h-aithntean. | ||

| Air gach latha ga’m bristeadh | ||

Gun bhonn meas air an t-Sabaid, |

||

| ’S mar creid sinn an Fhirinn | ||

| Theid ’ar diteadh gu bràcha. | ||

VII |

Cuim’ nach faigheadh sinn sùilean, | |

| Bho ’n triuir chaidh san àmbainn, | ||

| Chionn ’s nach deanadh iad ùmhlachd | ||

| Ach do na Duilean is Airde. | ||

| [57] ’Steach an sud chaidh an dùnadh, | ||

| Chionn ’s nach lubadh do ’n namhad, | ||

| Ach cha tug e orr’ tionndadh | ||

| Dh’aindeoin luban an t-Sàtain. | ||

VIII |

Ge d’ rinn iad seachd uairean | |

| ’Teasach’ suas a cur blàths ’innt’, | ||

Bha an creideamh-sa daingean: |

||

| ’Us soilleir, ’s cha d’ fhailing. | ||

| Cha robh snaithean air duin’ ac’ | ||

| No urrad ’us fabhrad, | ||

| Air a losgadh mu’n cuairt dhoibh. | ||

| Oir bha ’m Buachaile laidir. | ||

XI |

Tha cuid anus an t-saoghal, | |

| A bhios daonnan a tional. | ||

| ’Cuid eile a sgaoileadh, | ||

| Cha ’n ann gu saorsa do ’n anam. | ||

| Ach a riarach’ na feòla | ||

| Le ’n cuid roic agus caitheamh. | ||

| Ge b’ e dh’fhanas ’san t-seòl so, | ||

| Thig an lò bhios e, aithreach. | ||

X |

Oir cha ’n eil iad an tòir | |

| Air an t-sòlas nach teirig. | ||

| No smuain’ air an dòruinn | ||

| Gheibh mòran bhios coireach. | ||

| [58]Ge d’ a dh’ fhuiling ar Slàn’ear | ||

| Gu ’ar tearnadh bho Ifrinn | ||

| ’S iad a chreideas a thearnar | ||

| ’S theid cacha a sgriosadh. |

ORAN MOLLAIDH DO CHOIRIARARIDH: A SONG IN PRAISE OF COIRIARARIDH.

Coiriararidh, Altiararidh, and Easiararidh are so many links joined together in a local topographical chain. The burn flows from the Corrie, and joins the River Moriston at the Falls of Easiararidh, one of the most picturesque waterfalls in the Highlands. Here the Moriston rushes and tumbles over immense boulders and rocks of all sizes and shapes, extending laterally to a considerable breadth, and the mingled moan and roar, when the river is in flood, causes a peculiar and unique sensation.

It is a weird, unearthly sound — partly, we suppose, because of the echoes of the caves and fissures of the neighbouring rocks. One of those caves is sufficiently large to shelter a number of men. Here, tradition says, several archers in the interest of the Lord of the Isles lay in ambush, to shoot Patrick, the Second Laird, as he passed down on the opposite bank. He was, however, saved through the fidelity of Macianruaidh of Livisy, who discovered the plot.

[59] Of the author of this song we know only the name — Ewen Macdonald. It resembles Duncan Ban McIntyre’s poem of Coirecheathaich, but is somewhat more extravagant in its poetic license. It is in the same measure, sung to the same air, and is a composition of ability. As far as we know, it is the only specimen left us, of the productions of the author’s muse.

I |

Mu run Coiriararaidh sam bi an liath chearc, | |

|---|---|---|

| San coileach ciar-dhubh is ciataich pung. | ||

| Le chearcag riabhach, gu stuirteil fiata, | ||

| ’Us e ga h-iarraidh air feadh nan tóm. | ||

| An coire rùnach sam bi na h-ubhlan, | ||

| A fàs gu cubhraidh fo dhrùchdaibh tróm, | ||

| Gu meallach sughmhor ri tìm na dùlachd, | ||

’S gach lusan urair tha fàs san fhónn. |

||

II |

’Se Coire’n ruaidh bhuic, ’s na h-eilde ruaidhe, | |

| A bhios a cluaineis am measg nan craoibh. | ||

| ’San doire ghuanach le fhalluing uaine. | ||

| Gur e is suaicheantas do gach coill. | ||

| Cha ghabh e fuarachd, cha rois am fuachd e, | ||

| Fo chomhdach uasal a là sa dh’oidhch’. | ||

| Bith’ ’n eilid uallach sa laogh mu’n cuairt dhi | ||

| A cadal uaigneach ri gualainn tuim. | ||

III |

[60] Buidhe tiorail, torrach sianail, | |

| Tha ruith an iosail le mheïlsean feòir. | ||

| ’O n’ chlach is isle, gu braigh na criche, | ||

| Tha luachair mhin ann, ’us ciob an lòin. | ||

| Tha canach grinn ann, ’us ros an t-sioda, | ||

| ’Us luaidhe mhilltich ’us meinn an òir. | ||

| S na h-uile ni air an smaoinich d’ inntinn, | ||

| A dh’ fhaodas cinntinn an taobh s’ ’n Roimh. | ||

IV |

Tha sgadan garbh-ghlas a snamh na fairg’ ann, | |

| Is bradain tairgheal is lionmhor lànn. | ||

| Gu h-iteach meanbh-bhreac, gu giurach mealgach, | ||

Nach fuiling anabas a dhol na chòir. |

||

| A snamh gu luaineach, san sàl mu’n cuairt dha, | ||

| ’S cha ghabh e fuadach ’o ’n chuan ghlas ghorm, | ||

| Le luingeis eibhinn, a dol fo’n eideadh, | ||

| Le gaoth ’ga ’n seideadh ’us iad fo sheòl. | ||

V |

Tha madadh ruadh ann, ’us e mar bhuachaill’ | |

| Air caoraich shuas-ud, air fuarain ghorm. | ||

| Aig meud a shuairceas, cha dean e ’m fuadach, | ||

| Ge d’ bheir thu duais dha, cha luaidh e feòil. | ||

| Gum paigh e cinnteach na theid a dhìth dhiubh | ||

| Mur dean e ’m pilltinn a rithist beò, | ||

| ’S ged’ ’s iomadh linn a tha dhe shinns’reachd, | ||

| Cha d’rinn iad ciobair a dh'fhear de sheòrs’. | ||

VI |

[61] Tha ’n Leathad-fearna, tha ’n cois a bhràighe | |

| ’Na ghleannan àluinn a dh’arach bhò, | ||

| Toilinntinn àraich, a bhìos a thamh ann. | ||

| Cha luidh gu bràch air a ghaillionn reòt. | ||

| Bith’ muighe ’s càis’ ann, gu la Fheillmartuinn, | ||

| ’S an crodh fo’ dhàir a bhios mu na chrò. | ||

| Air la Fheillbride bith cur an t-sìl ann, | ||

| Toirt toraidh cinnteach a rìs na lorg. | ||

VII |

Gu dealtach féurach, moch maduinn cheitean, | |

| Tha ’n coire géugach fo shleibhtean gorm. | ||

| Bith ’n smeorach cheutach air bhar na géige, | ||

| Sa cruit ga gléusadh a sheinn a ceòil. | ||

| Bith ’n eala ghle-gheal, ’s na glas-gheoidh ’g eubhachd, | ||

| Sa chubhag ebhinn bho meilse glòir. | ||

B’ait leum fein, bhi air cnoc ’gan eisdeachd, |

||

| Sa ribheid féin ann am béul gach eòin. | ||

VIII |

Ge d’tha mo chomhnuidh, fo’ sgail na Sròine | |

| ’Se chleachd ’o m’òige bhi ’m chomhnuidh thall. | ||

| ’Sa Choire bhoidheach, le luibhean sòghmhor, | ||

| Is e a leòn mi, nach eil mi ànn. | ||

| Mo chridh’ tha brònach, gun dad a sheol air, | ||

| Sa liuthad sòlais a fhuair mi ann. | ||

| [62]’S bho n’ dhiult Ian Og dhomh, Ruidh’-Uiseig bhoidheach | ||

| Gur fheudar seòladh a choir na’n Gàll. | ||

IX |

Ge d’fhaighinn Rìoghachd a ni sa daoine, | |

| Cha treig an gaol mi, a tha na m’ chom. | ||

| A thug mi dh’aon, ’th’air a chur le saoir, | ||

| An ciste chaoil, a dh’fhag m’inntinn tróm. | ||

| Na ’m biodh tu làthair gu’m faighinn làrach, | ||

| Gun dol gu brach as, gun mhàl gun bhónn | ||

| A Righ a’s àirde, cuir buaidh ’us gràs | ||

| Air an linn a dh’ fhàg thu aig Hanah dhonn. |

Alexander Grant – Mac-Iain-Bhain – was born at Achanacoinearan, about the year 1772. He joined the army when very young, and had his full share of the hardships and dangers belonging to the stirring times during which he served. He served in the West Indies, in the Danish Campaign, under Sir John Moore, in Spain, and afterwards under Wellington. Eventually his health gave way, and he was obliged to return home. But his strength was not equal to the exertion, and he fell a victim to his malady in Glen-Urquhart, within a day’s journey of his much longed for home in his [63] native glen. His remains were first interred at Kilmore, but were afterwards removed to Invermoriston Churchyard, where they now rest with those of his ancestors. As will be seen from the following specimens of the productions of his muse, Grant was a poet of great merit.

A SONG IN PRAISE OF GLENMORISTON:

ORAN MOLAIDH DO GHLEANNAMOIREASTUINN.

This poem seems to have been composed soon after Grant joined his regiment, and is replete with tender recollections of his native glen, and the friends he left behind him. It also contains — as most of his songs do — beautiful descriptive touches. Grant excelled in this. He had acute powers of observation, as well as the faculty of utilizing what he knew in his own chaste mellifluous style.

I |

Thoir mo shoraidh le fàilte, | |

|---|---|---|

| Dh’fhios an àit’ bheil mo mheanmhuinn. | ||

| Gu dùthaich Mhic-Phàdruig, | ||

| ’San do fhuair mi m’ àrach ’s mi m’ leanaban. | ||

| Gar nach fhaicinn gu bràth i, | ||

| Cha leig mi chàil ud, air dhearmad. | ||

| [64] Meud a mhulaid bh’air pàirt dhiubh, | ||

| Aig an àm anns an d’fhalbh mi. | ||

| Seisd— Thoir mo shòlas do’n dùthaich, | ||

| ’S bith’ mo rùn di gu m’ éug. | ||

| Far am fàsadh a ghiùbhsach, | ||

| ’San goireadh smùdan air geig. | ||

| Thall ri aodan an Dùnain, | ||

| Chluinte thùchan gu reidh. | ||

| Moch maduinn na driùchda, | ||

An àm dusgadh do’n ghréin. |

||

II |

’S truagh nach mise bha'n dràsda, | |

| Far am b’ abhaist dhomh taghall. | ||

| Mach ri aodann nan àrd-bheann, | ||

| Stigh ri sàil Carn-na-fiuthaich. | ||

| Far am faicinn an làn-damb, | ||

| Dol gu dàna na shiubhal, | ||

| S mar beanadh leon no bónn craidh dha, | ||

| Bu mbath a chàil do na bhruthach. | ||

| Thoir mo shòlas, &c. | ||

III |

Gheibbte boc ann an Ceannachnoc, | |

| Agus earb anns an doire, | ||

| Coileach-dubh an Ariamlaich, | ||

| Air bheag iarraidh sa choille. | ||

| Bhiodh an ruadh-chearc mar gheard air, | ||

| ’G innseadh dhan dha roimh theine. | ||

| ’S ach na’n coisneadh i ’m bàs dha, | ||

| Thug ise gràdh do dh’fhear eile. | ||

| Thoir mo shòlas, &c. | ||

IV |

[65] Gheibhte ràc ’us lach riabhach, | |

| Anns an riasg an Loch-coilleig, | ||

| Coileach bàn air an iosal, | ||

| Mu Rudha-’n-iar-dhoire taghal. | ||

| Tha e duilich ri thialadh, | ||

| Mar cuir sibh sgialachd na m’ aghaidh, | ||

| ’S tric a chunnaic sinn sealgair, | ||

| Greis air falbh gun dad fhaighainn. | ||

Thoir mo shòlas, &c. |

||

V |

Gheibhte gruagaichean laghach, | |

| Bhios a taghal ’s na gleanntan. | ||

| Cualach spréidh ’us ’ga ’m bleoghann, | ||

| Tìm an fhoghair ’s an t-sàmhraidh. | ||

| ’M pòr a dheanainn a thaghadh, | ||

| ’S gur iad ’roghainn a b’ ànnsa, | ||

| Briodal beòil gun bhonn coire, | ||

| Nach tigeadh soilleir gu call dhuinn. | ||

| Thoir mo shòlas, &c. | ||

VI |

Tha mo chion air mo leannan, | |

| Leis nach b’ aireach mo luaith ri’. | ||

| Tha a slios mar an canach, | ||

| No mar eala na’n cuaintean. | ||

| Tha a pòg air bhlas mealla, | ||

| ’S gur glan ruthadh a gruaidhean. | ||

| [66] Suil ghorm is glan sealladh | ||

| Fo chaol mhala gun ghruaimean. | ||

| Thoir mo shòlas, &c. | ||

VII |

Feach nach eil thu an dùil, | |

| Gu ’m bheil mi rùin ’us tu suarach. | ||

| No gu’n cuir mi mo chùl riut, | ||

| Air son diombaidh luchd fuatha. | ||

| Tha mo chridhe cho dlù dhut | ||

| ’S an la’n tùs thug mi luaidh dhut, | ||

| ’S gus an caireir ’s an ùir mi, | ||

| Bith’ mo rùn dhut a ghruagach. | ||

Thoir mo shòlas, &c. |

||

VIII |

’S iomadh àite ’n robh m’ eòias, | |

| ’On chaidh mi m’ òige do’n armailt, | ||

| ’S luchd nam fasan gu’m b’ eòl dhomh, | ||

| ’O na sheòl mi thair fairge. | ||

| An caithe beatha, ’s an stuamachd, | ||

| Ann an uaisle gun anbhar. | ||

| Thug mi ’n t-urram thair sluagh dhoibh, | ||

| ’S an taobh-tuath as an d’fhalbh mi. | ||

Thoir mo shòlas, &c. |

[67]

A EULOGY ON THE CHISHOLM:

ORAN MOLAIDH DO SHIOSALACH SHRATHGHLAIS.

During one of his intervals of service in the army, the Bard went to a sale at Erchless, the seat of the Chisholm, to buy a cow. He bought the cow, but had the mortification of being refused delivery, as he had not the money in hand. The Chisholm saw the poet’s predicament, beckoned him to come to him, and said, “Alastair, if you promise to be back on such a day with payment, I will be your surety, and you shall have the cow with you.” “I promise,” said Alastair, cordially thanking his kind friend. He came back punctually on the day appointed, asked for an interview, and laid the money on the table. The Chisholm filled a glass, adding, “now, Alastair, drink my health.” Grant took the glass, and before drinking sang the following beautiful and highly complimentary effort of his muse, which so gratified the Chief, that in the handsomest manner he returned the money, and sent Alastair home a richer and happier man.

I |

So deoch-slàint ’an t-Siosalaich, | |

|---|---|---|

| Le meas cuir i mu’n cuairt. | ||

| Cuir air a bhord na shireas sinn, | ||

| Ge d’ chosd e mòran ghinidhean, | ||

| [68]Am botal lan do mhire ’n t-sruth, | ||

| Dean linne de na chuaich. | ||

| Olaibh as i, ’se bhur beatha, | ||

| ’S bithibh glan gun ghruaim. | ||

II |

Bheil fear an so a dhiùltas i, | |

| Dean cunntas ris gun dail. | ||

| Gu ’n tìlg sinn air ar culthaobh e, | ||

| Sa chomunn so cha ’n fhiugh leinn e, | ||

| An dorus theid a dhunadh air, | ||

| Gu druidhte leis a bhàr. | ||

Theid iomain diombach chum an duin, |

||

| Ma’s mill e ’n rum air cach. | ||

III |

Is measail an àm tionail thu, | |

| Fhir ghrinn is glaine snuagh | ||

| Le d’ chul dónn daite camagach, | ||

| Cha toireir cuis a dh-aindeon dhiot. | ||

| ’Us cha bu shugradh teannadh ruit, | ||

| An an-iochd no ’m beart chruaidh. | ||

| ’S mi nach iarradh fear mo ghaoil, | ||

A thighin’ a’ d’ thaobh fo’ d’ fhuath. |

||

IV |

Na’n tigeadh feachd an namhaid, | |

| Do’n chearnaidh so ’n Taobh-tuadh. | ||

| Bhiodh tusa le do Ghàidheil ann, | ||

| Air toiseach na’m batailleanan, | ||

| [69]'Toirt brosnachaidh neo-sgàthach dhoibh, | ||

| Gu cacha chuir san ruaig. | ||

| Is fhada chluinnte fuaim do làmhaich, | ||

| A toirt air làraich buaidh. | ||

V |

S’ na ’n éireadh co-strigh ainmeil, | |

| A ghairmeadh sinn gu cruas. | ||

| Bhiodh tusa le do chairdean ann, | ||

| Na Glaisich mhaiseach laideara, | ||

’Us cha bu chulaidh fharmaid leum |

||

| Na tharladh oirbh ’san uair: | ||

| Le luathas na dreige, ’s cruas na creige | ||

| A beumadh mar bu dual. | ||

VI |

Is sealgair fhiadh san fhireach thu, | |

| Le d’ ghillean bheir thu cuairt, | ||

| Le d’ cheum luthmhor spioradail, | ||

| ’S do ghunna ùr-ghleus innealta, | ||

| Nach diult an t-sradag iongantach, | ||

| Ri fudar tioram cruaidh. | ||

| Bu tu marbhaiche damh-croic | ||

’Us namhad a bhuic ruaidh. |

||

VII |

Cha mheas’ an t-iasgair bhradan thu, | |

| Air linne ghlan na’m bruach, | ||

| Le d’ dhubhain dhriamlach shlat-chuibhleach, | ||

| Le d’ mhorgha gobhlach sgait-bhiorach, | ||

| [70]’S cho deas ri aon a thachras riut, | ||

| Le’ d’ acfhuinn tha mi luaidh, | ||

| Cha n eil innleachd aig mac Gaidheil | ||

Air a cheaird tha uat. |

||

VIII |

Is iomadh buaidh tha sìnnte riut, | |

| Nach urrar innse n’ drasd’. | ||

| Gu seimhidh suairce siobhalta, | ||

| Gu smachdail beachdail inntinneach, | ||

| Tha gràdh gach duine chi thu dhut, | ||

| ’S cha ’n ioghnadh ge d’ a tha, | ||

| ’S nasal eireachdail do ghiùlan, | ||

’S fhuair thu cliù thair chach. |

||

IX |

’Us fhuair thu céile ghnàthaichte, | |

| Thaohh nadur mar bu dual. | ||

| Fhuair thu aig a chaisteal i, | ||

| ’S da ionnsuidh thug thu dhachaidh i, | ||

| Nighean Mhic-’ic Alastair, | ||

| ’O Gharaidh nan sruth fuar. | ||

| A slios mar fhaoilinn, gruaidh mar chaorann, | ||

| Mala chaol gun ghruaim. |

[71]

A VOYAGE TO THE WEST INDIES: “’N DIUGH ‘S MI FAGAIL NA RIOGHACHD.”

Both this and the following song, record some of the terrible incidents during the voyage of Admiral Christian’s fleet to the West Indies in the winter of 1799. Shortly after it left the harbour, they encountered a terrific storm. The fleet was dispersed, several men-of-war, as well as many lives, were lost. In describing this storm and its consequences, the poet’s powers are in full play. We see the wild scene — the mountain waves, the broken masts, the tattered sails, and the deck swept of its belongings — sheep, cattle, and marine furniture. It must have been a trying ordeal to our young poet at the outset of his military life.

I |

IAn diugh ’s mi fagail na rioghachd, | |

|---|---|---|

| ’S mor mo mhulad ’s mo mhi-ghean ’san am. | ||

| Dol a sheoladh thar chuaintean, | ||

| Do na h-Innseachan-shuas uainn air ball. | ||

| Cha robh ’n turus ud buadhach, | ||

| Dh’ éirich gaillionn ’us fuarachd ro theann, | ||

| ’N uair a thainig a chuairt ghaoth, | ||

| Thug e leatha ’bho ruadh ’o na ghleann. | ||

II |

[72]Mios an deighe na Sàmhna, | |

| ’S goirt an sgabadh ’s an call a bh’ air cuan. | ||

| Thainig toiseach a gheamhraidh | ||

| Ann an gaillionn ’s an campair ro chruaidh. | ||

| Chunnaic mise le m’ shùilean, | ||

| Daoine dol do na ghrunnd aig gach uair, | ||

| ’S mar ri so, bha mi ’g acain | ||

| An tónn mo dheadh leabaidh thoirt uam. | ||

III |

Sud an oidhche bha éitidh, | |

| Bha mhuir dhu-ghorm a ’g éiridh gu h-àrd | ||

| Chaidh a chabhlach ’o chéile, | ||

| ’S dh’ fhagadh sinne ’nar n-eiginn ’s nar càs. | ||

| Chaill sinn buaile na spreidhe. | ||

| Dhiobair aisnean a cleibh’ as a tàr, | ||

| ’S cha dean mulad bonn féum dhuinn, | ||

| Ged’ nach faiceadh sinn feudail gu bràth. | ||

VI |

Dh’fhalbh a cheardach a dh’ urchair, | |

| Eadar innean ’us bhuilg agus ùird. | ||

| ’S thug i bóid nach bu tamh dhi, | ||

| Gus am faiceadh i c’ àit’ an robh grunnd, | ||

| Ma bha teas anns na h-iarruinn, | ||

| Bha ’san teallaich ’cur rian orr’ a ’s ùr. | ||

| Chaidh e asd’ ’us air dhi-chuimhn’, | ||

Greis mu’n d’ rainig iad iochdair a bhuirn. |

||

V |

[73] Tha rud eil’ air mo smaointean, | |

| Thugaibh barail am faod e bhi ceart. | ||

| Dh’fhalbh an cù le’ na caoraich, | ||

| ’S cha robh ’n rathad ud faoin tha mi ’m beachd. | ||

| Cha ’n urrainn mi innseadh, | ||

| An deach iad air tìr no nach deach’. | ||

| Ach na’m b’aithne dhoibh iomradh, | ||

| Thug iad bàta fo ’n imrich a mach. | ||

VI |

Thainig call air an Ebus, | |

| Bhris a cruinn agus réub a cuid seòil. | ||

| Leig an t-Admiral taod ri, | ||

| Dh’ fheach an tearnadh e ’dhaoine dhi beò. | ||

| ’N uair a dhealaicht’ am bàta, | ||

| A chaidh ’mach gu’n toirt sabhailt gu shore, | ||

| Ceart mar dh’ fhuasgail a hawser, | ||

| Chaidh i fodha mar smàladh an leois. | ||

VII |

Na’m biodh fios aig mo mhathair, | |

| Mar tha mis’ air mo charamh ’s mi beò. | ||

| Mar tha sruth ’o mo ghuaillean, | ||

| Tigh’n le farum troimh fhuaghal nan cord. | ||

| Cha b’fhois ’s cha bu tamh dhi, | ||

| Bhiodh a leabuidh air snàmh le’ na deòir. | ||

| ’S bhiodh a h-ùrnuigh ri Slàn’fhear, | ||

| Righ nan dùl mo thoirt sàbhailt gu shore. | ||

VIII |

[74] Feumair innseadh dhuibh ’nise, | |

| Ceann mo sgeòil: tha mi fiosrach gu leòr. | ||

| ’O na dh’ ardaicheadh Criosda, | ||

| ’S ’o na shoillsich a ghrian ud ‘s na neòil. | ||

| Seachd-ceud -deug, ’us ceithir fichead, | ||

| Naoi deug tha mi meas do na chòrr, | ||

| ’S ma gheibh sinn ùine ri fhaicinn, | ||

’Si bhliadhn’ ur a cheud mhaduinn thig oirn. |

VOYAGING: “IS CIANAIL AN RATHAD.”

|

I |

Is cianail an rathad, | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

’S mi gabhail a chuain. | |

|

|

Sinn a triall ri droch shide, | |

|

|

Do na h-Innseachan-shuas. | |

|

|

Na cruinn oirn a lùbadh, | |

|

|

S na siuil ’ga ’n toirt uainn. | |

|

|

An long air a leth-taobh, | |

|

|

A gleachd ris na stuaigh. | |

|

|

||

|

II |

Di-ciadain a dh’fhalbh sinn, | |

|

|

Bu ’ghailbheach an uair. | |

|

|

Cha deach’ sinn mór mhiltean, | |

|

|

’N uair shin e ruinn cruaidh. | |

|

|

[75]’S gu ’n do chriochanaich pairt dhinn, | |

|

|

’S àit’ ’san robh ’n uair. | |

|

|

’S tha fios aig Rock-sàile, | |

|

|

Mar thearuinn sinn uaith. | |

|

|

||

|

III |

Seachd seachduinean dùbailt, | |

|

|

Do dh’ùine gle chruaidh. | |

|

|

Bha sinne fo churam, | |

|

|

Gun dùil ri bhi buan. | |

|

|

’Sior thaomadh a bhuirn aisd’ | |

|

|

’Reir cunntas nan uair, | |

|

|

’S cha bu luaith dol an diasg dhi | |

|

|

No lionadh i suas. | |

|

|

||

|

IV |

Tha onfhadh na tìde, | |

|

|

’Toirt ciosnachadh mòr, | |

|

|

Air a mharsanta dhìleas, | |

|

|

Nach diobair a seòl. | |

|

|

Tha tuilleadh ’sa giulan, | |

|

|

Aig usbairt ri sroin. | |

|

|

’S i’n cunnart a muchaidh, | |

|

|

Ma dhuineas an ceò. | |

|

|

||

|

V |

Tha luchd air a h-uchd, | |

|

|

A toirt murt air a bord. | |

|

|

Neart soìrbheis ’o ’n iar, | |

|

|

A toirt sniomh air a seòl. | |

|

|

[76]Muir dhu-ghorm éitidh, | |

|

|

Aig éiridh na còir. | |

|

|

’S le buadhadh na seide | |

|

|

’S tric eiginn tigh’n oirn. | |

|

|

||

|

VI |

Tha gaoth ’us clach-mheallain | |

|

|

A leantuinn ar cùrs’. | |

|

|