"Story and Song from Loch Ness-Side" |

| By Alexander Macdonald |

| Chapter X |

| Of Sickness, Death, Wakes and Funerals |

[149]

In olden times rather peculiar ideas prevailed regarding sickness. In their attitude to it the Highland people have been largely fatalistic, though the Celtic race, as a whole, as is amply proved by the numerous treatises on medical subjects which still exist, were not indifferent to the healing art; yet they did not always place too much faith in the doctor, though they enjoyed the services of some very able representatives of the medical profession. The following story is suggestive in this connection: An old wife had a cow which fell ill. During the cow's illness the minister came the way, and the old wife would have him see the sick cow. After examining the animal he made the sage pronouncement, addressing the cow: "Ma bhios tu beo bithidh, 's mar bi bithidh tu marbh" ("If you will live you will live, and if not you will die"). Some time thereafter the minister himself was suffering from an affection of the throat. In course he had a visit from the old wife, who, after looking at him for a while as he lay on his bed, sagely repeated: "Ma bhios tu beo bithidh, 's mar bi bithidh tu marbh" ("If you will live you will live, and if not you will die"). Remembering his own words in the case of the cow, he fell into a fit of laughter, which, it is said, had the effect of bursting the abscess in his throat; and he was soon afterwards quite well again. There is little doubt that in days gone by a great deal was suffered before real effort was [150] made to apply remedies. In the first place, as indi cated, the idea prevailed that whoever was destined to get better would recover, and that whoever was doomed to die was beyond cure. But the olden-time people must not be considered as making no effort at all to grapple with sickness. On the contrary, almost every parent knew well what to do when trouble visited the family, though there would appear to have always been a suspicion of the mysterious in the background. For a time - and until not so long ago - bleeding was much in vogue all over the Highlands as a treatment in almost every form of disease. But even this was not without its spice of superstition. It was thought that if the blood when let did not spurt furiously out over the bed there was very grave danger of a fatal termina tion. Again, some practitioners were considered more lucky than others.

A very common specific in most ailments was whisky, the belief in which would seem to have at one time been so strong as to indicate that the person whom a few glasses of good quality did not cure was really not worth curing at all! And, it must be admitted, that in a great many cases the national beverage seemed to justify the high expectations held as to its efficacy, and established for itself a wide reputation as a " medicine" of no ordinary potency. It was the great specific for smallpox. One of the commonest medicines in use was castor-oil, which was supposed to be always safe, whatever was wrong with man, woman, child, or beast - and the old people were not in their belief in "the oil" very far wrong upon the whole. A common habit was to gather round the sick-bed, as if the sickness would lose its hold in ratio [151] to the number present. Isolation was out of the question, and fear of infection was absent, until there was reason for it; then everybody fled. Charms and incantations played an important part in connection with ill-health of all sorts for many long periods of time back, and probably all traces of them have not yet entirely disappeared. Herbs were, however, very much in evidence, and this was, of course, of greater importance. There was a general acquaintance with their uses, and some persons, who made a special study of them, were very effective with those cures. There was an excellent one, for instance, for a persistent cough. It consisted of a decoction of the herb called Dog- carmillion ("Torbhuill-a'-Choin"),made in the follow ing manner: A small quantity of the root was pulled, then scraped and washed; thereafter put into a vessel containing about two cupfuls of water, and infused like tea. Sugar and cream were added, and about a cupful taken twice daily - in the morning and at night. The cure was immediate and decisive. This remedy was also given in cases of persistent diarrhoea or dysentery, with unquestionably satisfactory results. The prin cipal virtue of the root seemed to be its power for the immediate creation of new skin, or membrane, wherever such was required. Equally effective in healing flesh wounds, or cuts of all descriptions, was the Rib-wort ("An slan lus"). A leaf of the plant was plucked and put into the mouth, then chacked well with the teeth - during which process it became well saturated with saliva - and applied to the wound. The cure was certain.

Falling-sickness was somewhat common in the dis trict at one time; and King's Evil was not unknown, [152] For those troubles charms were very much in demand,, as the causes were generally supposed to be supernatural. There was the common belief that the seventh son could cure either of those ailments. Such human frailties as colds, rheumatic affections, sore heads, sore bones, stitches, colics, constipation or looseness, sore throat, skin diseases, and, in short, all the more common and less serious troubles appeared to have been looked upon as if they ought to exist from time to time. Little notice was taken of them except in so far as to treat them by the simple methods known to the people them selves. Hot milk, gruel, warm applications, castor-oil, herbs, and whisky were the common remedies.

There was, of course, a number of persons who were always unwell, but never getting worse, and who were looked upon as not really suffering at all. When, how ever, the big, strong man, Allie, was reported very ill, it was at once agreed that his case was not a sham. Several visited his house, and found him far from well. Regardless of consequences, the room in which he lay was much crowded, and the talk was prodigious. Every one diagnosed. One said it was a case of galloping consumption; another that it was ricketts; a third that it was rheumatism of the spine;a fourth (quietly) that it was death; and so on. After mature and serious thinking, and the waste of tremendous energy in speak ing, it was at last decided to send for the minister. The nearest doctor lived some six miles away, and the case was not yet considered bad enough to call him in. The parson was in his way not a bad physician. He was none other than the Rev. Mr Gair, of the Established Church, in Invermoriston, elsewhere noticed. After the decision to consult Mr Gair, the selection of a suitable [153] deputation became necessary;and that was a great question. It took considerable time and language to- settle the subject; but the matter was, however, eventual ly arranged. The manse was about one mile distant at the foot of a steep brae. With this for their destinat ion, away the party went. It was a bleak, cold, winter night, and the blast from the north-west was bitterly felt before getting into the shelter of the woods. Arriving at the manse in due time, the good man immediately prepared to accompany the messengers back. He mounted the pony provided, and the little animal, findi ng its head turned homewards, walked briskly, the deputation following silently. Long before arrival at the house, stray parties were met, all possessed by a feeling of expectancy, and even curiosity; and when the little cottage was reached wherein lay the sick man, the company consisted of a large proportion of the whole population of the township. The examination by Mr Gair was very intelligent. He pronounced the illness as not dangerous, prescribed warm fomentations and rest, and gave a mild medicine. Then the kind and genial pastor returned home, and two or three of the young men present accompanied him. Later on, however, the pain in the patient's chest increased, and an old man who sat beside the bed felt inspired to experiment. He called for a thick slice of loaf-bread, which, after toasting it at the peat fire, he buttered generously. This he placed on the spot where the pain was most felt. In a short time there was an improvement. But that was not all;towards midnight the patient expectorated a quantity of clotted blood, and from that moment he began rapidly to mend.

[154] Our story reminds us that we should make suitable reference here to one lay "doctor'' among us who was remarkably clever and successful in his way. Donald MacDonald, commonly known as "The Carrier" - a name he had got from having been carrier to Mac- Phadruig before the days of steamers - was of an intelli gent family, and naturally smart. As a young man he was, for some time, horseman to a doctor at Fort- Augustus, and it was supposed that he picked up some useful knowledge in that way. As a bone-setter he was eminently successful, and performed operations that would have done credit to any trained practitioner. But he did not confine his operations to bone-setting alone; when bleeding was in vogue, and had to be performed, he was quite skilful with his lancet;when inflammations raged, he was there with his poultices;when animals sickened, or anything went wrong with them, he was at hand, and always prepared with a suggestion, an advice, or some other service, which generally led to a successful result. There was probably no more useful man within a wide radius than the good old "Carrier", whose joke was as pithy as his heart was warm. His death a few years ago brought about an immense missing.

A momentous day in the life-history of our High lander of old was that of his death. The great leveller, the black messenger from the Unknown beyond, seems to have always impressed itself on the Highland mind with peculiar effect. Did it not break up homes, sever friends and relatives for ever, and generally dislocate the possibilities of happiness? But death, nevertheless, annexed the ancient Highlanders with as little ceremony as others; but it was to them, perhaps, the subject of [155] more superstition than to most people in the British Isles. In dreams and omens numberless it cast its shadow before. At all times the ghastly visitor struck terror and awe into the Highland mind, and this, possibly, was the reason why the ancient Gaels indulged in such a multitude of beliefs and curious rites of which the great Reaper was the centre figure.

An important institution connected with death in our district, particularly in the long ago, was the "wake" and the times are not yet, indeed, out of people's memory when wakes were of quite a different character from what they are now. A few generations past, when a person died people came to the house of mourning from far and near within a certain radius, to condole with the relatives of the deceased, and help them in keeping watch. Elderly persons visited by day, as a rule, and the young at night. So far, the same custom exists still that was in vogue then. But many of the features which were at one time characteristic of it have entirely disappeared. In bye-gone time, we are told, a wake was made the occasion of considerable merriment. The fiddler made it his duty to tramp a number of miles in order to supply music. The piper also appeared, and officiated at the function. Dancing was engaged in with enthusiasm. Marriages sometimes followed upon the acquaintances formed. Refreshm ents were served freely. When smuggling came into full swing the necessary liquor could be provided at much less cost than now. It was at one time nothing uncommon for a family to smuggle their own whisky, just as required.

For many years back now, however, dancing, or any thing of that kind, has not been indulged in at wakes. [156] The people adopted long ago such milder forms of passing the time as the telling of tales and the singing of laments and hymns. The tale-telling took pretty much the same form as at a ceilidh, and was generally entrusted to the ''Seanachie'' - the acknowledged authority - who, seated snugly in a convenient corner, narrated story after story with all the confidence of the local "Blind Harry." The tales related were, to say the least, of great interest, and embraced every subject- within the compass of the ordinary Highlander's intelligence; and it is now undoubtedly to be regretted that nobody thought of writing down, for preservation, the material thus brought to the surface from time to time. There cannot be any manner of doubt that much of the information submitted was of an important character. Many of the great houses in the Highlands were referred to, and the character of the chiefs and their ladies freely discussed; while the rising heirs formed subjects of much speculation. When purely Highland story became exhausted, a favourite theme at wakes was Scottish history, the people's knowledge of the chief events and the principal actors in the evolution of which was very considerable. They had learned much concerning the heroic achievements of the mighty men of the past - Wallace, Bruce, the Douglasses, and such.

From this pedestal there was but a. step to the doings of the free-booters or rievers, of which class of hero Rob Roy was considered the typical head. His acts of daring were a subject of never-failing attraction. "Colla-nam-Bo" ("Coll of the Cows"), "Domhull-Ban- Cailleach" ("Fair Donald Cailleaoh"), "Domhull Donn" (" Donald MacDonald, Bohuntin"), had each his turn.

[157] Stories of giants were a favourite topic. Cuchullinn, Fionn, Diarmad Donn, Goll MacMhorna, Oscar, Conan, Caoilte, and all the other heroes of the ancient- ballads were brought under contribution; while, of course, the strongest of all men who ever lived, Samson, was held "chief among tens of thousands".

We must not forget to mention one giant of later years who bulked very largely in the popular imagination when heroism was the theme. This was Samuel MacDonald ("Somhairle Mor"), a native of Sutherland, who was unmistakeably a remarkable specimen of the human race. The feats of strength performed by Big Sam - which were numerous - appealed to all, and were of a nature to interest and to inspire. We used to hear of one of those, the particulars of which were related by an old acquaintance. It would appear that a certain Italian challenged Sam to a fencing contest. For a time the foreigner kept the Highlander busy on the defensive. After a few turns, however, Sam got his chance, and playfully held the Italian up on the point of his sword, for the entertainment of the lookers-on. Sam passed the most of his manhood in the army. While in the Sutherland Fencibles, on service abroad, he was left one night in charge of a canon, but, feeling cold, he shouldered the big gun and took it inside, believing that he could as well watch over it there as outside. It may be here stated that we find this same story- related of "Big John Mackay, the Renter," by Sir Thomas Dick Lander in his "Highland Legends".Sam was probably the biggest man in Britain in his day. He stood seven feet four inches in height and was of immense strength. He had a special allowance from the Duchess of Sutherland towards his diet. [158] Sam was an unusually small and weak child when born, and it was said that he was fed on mare's milk, owing to his mother having been unable to nurse him.

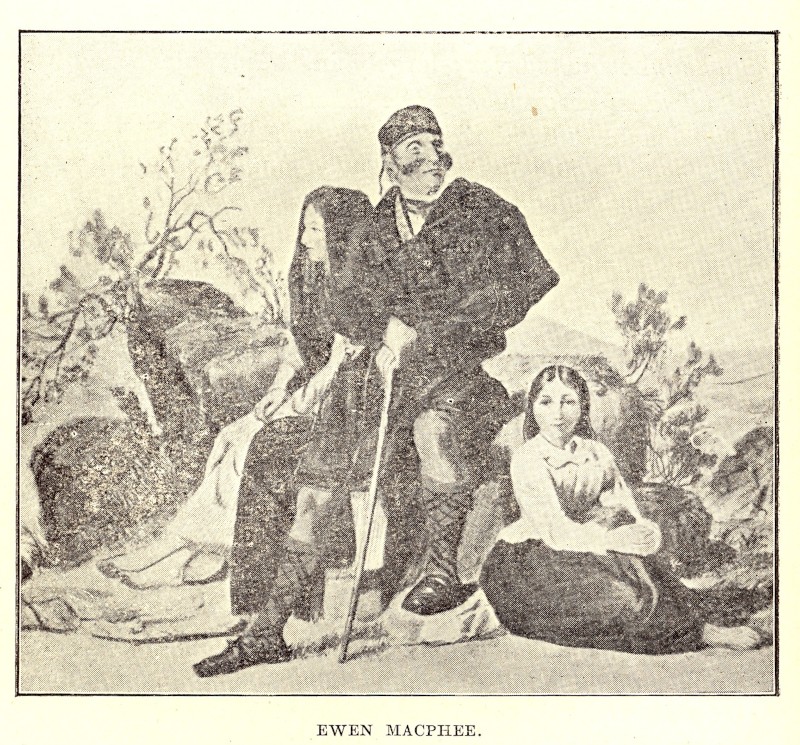

[Illustration] A man whose boldness and daring were frequently the subject of passing reference was Ewen Macphee ("Eoghann Ban a' Choire Bhuidhe"). Ewen was a native of Glenquoich. As a young man he enlisted in the army, but, preferring a free life, he deserted from his regiment. He was captured, but escaped a second time, and settled down at Corry-Buie, where he lived by dealing in goats, supplemented by fishing and [159] shooting. He was somewhat feared as a rather diagreeable c haracter, and he acquired a wide reputation for the possession of powers of no ordinary kind, and for being deeply versed in certain charms. Having got into trouble, he removed from Corry-Buie, and established himself on a small island in Loch-Quoich, where he lived for a while, defying authority and law alike. He was, however, eventually deprived of his stock while one day from home;and though he made strenuous efforts to fight the powers, modern conditions, of course, prevailed. MacPhee was a man of great personal strength and courage. He was married, and had a family. He died in Fort-Augustus about 1850.

As was quite appropriate, the story-telling occas ionally ran a good deal in the way of calling up weird, uncanny experiences in ghost-seeing, and the supposed dealings of those unsubstantial denizens of space with certain members of the human family. As may easily be fancied, all this at a wake proved uncomfortably suggestive, and a good few of those present did not take a very deep interest in the various subjects introduced. Fear, with all its dark possibilities, struck their hearts, and when one's turn came to go outside, or even to the lobby ("cul-an-dorus-bhig") for peats to put on the fire, courage was at a low ebb indeed. Frequently two would be required to get necessary services away from the fireside attended to.

But all were not alike in this respect, and the story was told of a man who suggested, at a certain wake, that something should be done to frighten a few young people who were expected to attend. It was agreed that nothing could be better for this purpose than to place the corpse in a standing position near the door. [160] But before this could be done, it was necessary to procure a substitute for the dead man. Who would volunteer? There was something repulsive about the suggestion, and there was also much superstition as to the ill-luck likely to follow the experience. But there was present one who agreed to take all risks. Accordingly the corpse was at once raised, and placed against the side-wall of the house, in a threatening, uninviting attitude, while the man allowed himself to be shrouded on the stretcher. For a time all went well. The people whom it was intended to frighten arrived, and there was no sensation. Then it was considered time that the corpse should be placed back on the stretcher, and the substitute relieved. He was requested to rise, but from him there was no response. Again he was spoken to, but not a word escaped from his lips. Had he slept? He felt dreadfully cold! What was the matter? He was dead!! Then there was great excitement, much talk and remorse; and the opinion prevailed that death should not be courted. Stories of corpses having risen up and read portions of Scripture were freely related In the olden days along the Glenmore Valley, and elsew here in the Highlands.

Advantage was sometimes taken of wakes for raffling purposes. A watch, a chain, an old clock, or some such article was usually put up and raffled for. As a rule in those cases the prize was returned to its owner. Highland pride was too high to appropriate anything unless it happened to be obtained in a manner consiudered honourable and manly.

Singing was perhaps, par excellence,the most inter esting and most popular means of passing the time at olden-time wakes. Gaelic poetry was, of course, most [161] drawn upon, and more especially laments, hymns, and songs of sorrow. There was a joy of grief which these beautiful compositions suitably expressed. Two well- known singers - men or women - were picked out, and, hand-in-hand, they sang often during the long watch. The compositions usually selected were the "Orain Mhora" ("The heavy Songs") of the bards. These had been composed to certain deep-strained melodies, such as "Gaoir nam Ban Muilleach" ("The Dirge of the Mull Wives"); "Sochdair Dhanachd na h-Alba" ("The Pride of Albanic Song"); "Crodh Chailein" ( "Colin's Cattle"); "Cumha Mhic-Leoid" ("MacL eod's Lament"); the air of "Lochaber No More," and others; while the hymns composed by Dugald Buchanan, Peter Grant, and the Apostle of the North - Dr John MaeDonald, of undying fame - were very popular also.

But matters have still further altered. On the whole now-a-days less interest is evoked by a wake. The visits of sympathisers are of shorter duration, and the event is undoubtedly much more as it should be. Yet we are not to condemn the old order of things as at any time wicked or barbarous. It was a survival of earlier customs which were in a transition state when we become acquainted with them in the social life of our forefather's.

There was also, at one time, a certain necessity for watching the dead, so that the bodies might not be stolen. In the early part of the nineteenth century body-snatching in the Highlands was by no means unc ommon. One day a woman, travelling to Inverness, was overtaken about Abriachan by a cart occupied by some two or three men, and asked to step up beside [162] them. Nothing unusual happened on the way till the party were nearing the town, when, on looking round,. she noticed a toe protruding through a loose covering,, which, on closer examination, indicated clearly the outl ines of the human form. Needless to say, the woman felt very much startled. But she had the discretion not to show in any way whatever that she suspected any such thing as a corpse being in the cart. Similar experiences were quite common; and people often enough watched for some six weeks even after the burial. In fact, there were in most churchyards small shelters where the watch was kept. In the little build ing the watchers had a fire, some refreshments, a pistol or an old gun, and a sword. Warm skirmishes between them and the "snatchers" were not unknown. The latter, of course, could expect little mercy when caught red-handed in the act of desecrating a grave. The ugly business was one which made way from the South, and the Highlanders hated it. It used to be told that it met with a severe check in the Inverness district through one of the most notorious of the "traffickers" having been served with the body of his own child.

After the wake came the funeral - an institution of exceptional importance in the Highlands of Scotland. The ceremony of burying the dead has always been one of great and outstanding interest among all races, and in all ages; and though time has considerably modified people's observances in connection with it, yet some of the earliest peculiarities attached to it may still be traced in present-day customs. This is eminently true as regards the Scottish Highlands. Glaring supersti tion has undoubtedly disappeared to a great extent, but there exist feelings of a kind at this very day in the [163] Highlands which tend to show that, in relation to the dead, the Highlander's beliefs and ideas have merely shifted ground. In our district the old custom of taking the coffin out of the house feet foremost has, since time immemorial, been - as it still is - in vogue. When one is asked why this is so, ignorance of the cause is generally pleaded, it being merely stated that such has always been done; and people would not on any condition violate a custom of such importance as this is believed to be. It can scarcely be realised that this very custom is a more or less universal one, that can be properly enough classed among many other such believed in at one time as a security against the possible return of the dead person's ghost to trouble the living. The point of faith here is that the ghost cannot find its way back into the house when taken out in the manner shown - one somewhat similar to that involved in the old practice of taking corpses out through a hole in the house-wall, so that the ghost, even if it returned, could not find the door, and, disappointed thus, have to go back to where it came from.

Hearses have not become common as yet in country districts, though, occasionally, one is seen in certain of the more populous centres, and the remains are carried in the manner of the past. When a coffin is brought outside it is placed upon a bier - an ugly, uninviting object, made of boards put together exactly in the form of a coffin, and held firmly by three cylindrical bars of wood, which project on both sides, thus making six in number. It is by these that the bearers carry the bier with its burden to the graveyard. When, however, in the olden days, a funeral had to travel a long distance, the coffin was carried on the people's shoulders, and a [164] bier to suit the occasion was made of two long poles of wood, bound together by withes. For some time past now, this has been giving way to better facilities.

Before leaving with a funeral it is still not un common to serve a round or two of whisky, with some bread or biscuits and cheese. A funeral used to be considered a poor function unless at least two drams were offered right off, and three made it one to be remembered. There should also be a round or two at the grave, and possibly one on the way. It would be useless to deny that certain persons heartily enjoyed a funeral. It is told of one such that, after getting pretty liberally treated at one of those functions, in giving thanks he expressed himself as very much obliged, saying - "Falbh! Falbh! Gu'n robh moran math agaibh, 's gum a fada tiodhlacadh agaibh" - ("Well, well! Many thanks to you, and long may you have a funeral") - scarcely a healthy wish.

Some persons were anxious as to the kind of funeral their relatives would honour their dead bodies with. It is a point on which a typical Highlander was always characteristically solicitous. One good story is told of a man who, when on his death-bed, got into a business conversation with his family as to his burial arrange ments. He gave the most explicit instructions as to what he wished done, and is reported to have concluded by saying that, of course, as he would not be there himself to see things properly carried out, nothing would be in order. This, however, is a most interest ing trait of humanity, and one which shows itself far, far back in the history of mankind. Among many other nations, the Jews, for instance, were much con cerned as to their being decently and honourably [165] buried. It was a. living element in their character and conduct through life. It would seem as if no greater disgrace could befall them than to be treated at death like "the beasts that perish". It was a good senti ment, too; suicides were practically unknown wherever it existed, and the modern indifference to a respectable funeral which sometimes exists is not nearly so healthy. In the olden days, after a funeral left, the women of the place were invited to the house of mourning and treated - a custom not yet wholly extinct. After copious expressions of condolence by them, which were much more natural than the cold card or letter of society, the good qualities of the deceased were elo quently referred to, and it was evident that the departed one was not to be forgotten immediately. By-and-bye the sorrow found some compensation in the belief that the visitation was not unexpected. Had not one here and there had a vision of the sad event? Had not also been seen in the gloaming a great number of people standing up in the very place where they gathered that day? Then it came to be remembered that the dogs about had been barking furiously every night for weeks; that a strange light had been seen, some time previously, in the very spot where the bier was placed on chairs by the side of the house; and that a certain party, coming home late, experienced a serious fright, a night or two before the death, just as he was turning the corner of the bridgend.

In Glenmoriston, as in various parts of the High lands, when funerals travelled from one district to another, it was customary - and still is - to raise cairns to the memory of the dead, about mid-way between the two districts. Each one attending the funeral looked [166] about for a stone or two, and in a very short time a cairn, with a bit of a slab stuck into its apex, reared its head above ground. It was this custom undoubtedly that gave rise to the word - "I will add a stone'' - or "another stone" - "to your cairn". As a rule, a dram was supplied when a cairn was completed.

Until some fifty years ago or so the piper regularly attended the burial even of the poorest. And this was a service in which, we think, the bagpipe found a place to which it is pre-eminently suited. To hear the sad and weird notes of one of those beautiful pibrochs, sounding and re-sounding 'twixt valley and glen, as the mournful procession wended its way slowly along, was, without .any shadow of doubt, one of the most impressive experiences in the Highlander's life. The presence of the piper at funerals was, in our opinion, simply an especially proper institution. As well as becoming impressiveness, the bagpipe lent a majesty, a nobility, and a dignity to an important and solemn occasion.

The churchyard was always considered a sacred spot. Each family - or head of a few families, as in some instances - had their own corner of "God's acre", just as they had their own pew in the church. Here the different members of the family were from time to time buried, and with scrupulous regard to space. When a stranger came to be interred in our cemetery it was usual to place some silver in the grave with the coffin, by way of purchasing a right to the soil, or alternately, to bury the remains in a part of the graveyard not previously used. Rather serious squabbles sometimes arose out of one family encroaching on another's portion of this, to them, holy ground. But these disturbances were [167] avoided by the more thoughtful, because it was believed that those who took the initiative in any such got more than enough of the churchyard for a time afterwards. After a family had been long away from a district it was no easy matter to distinguish the plot belonging to them when the remains of a representative came to be interred. Then a local "seanachie", who was always considered an infallible authority, was consulted. We have known one such to have been totally blind, and yet able to point out any grave or family resting-place in the churchyard, and, at the same time, give details of burials for generations back.

It has, unfortunately, to be confessed that High land funerals were at times made occasions for some rough fights, which were anything but creditable to those taking part in them. This class of disturbance practically disappeared long, long ago now, though one such occurred now and again within the past few generations. The story is told of .a certain native of Glenmoriston having died many years ago, the burial of whose remains became the subject of an alarming squabble. The coffin containing the remains had been taken outside the house, and, as the procession was about to start, a warm contention, got up between a gentleman from Kintail and an influential native as to the question of precedence as chief mourner. Soon the respective disputants were joined by others, and neither party felt certain as to what the lifting of the bier might bring about. Words sounded high all round, and indi cated that there was to be a skirmish; and here comes ill a touch of characteristic setting-off to the story. A man looking out by the window of the house from which the remains had been taken, made himself believe that [168] he saw the Evil One busily going about among the people, placing his black finger on a shoulder here and there ; and the conclusion he came to was that his Satanic majesty was instigating those to the fight. The remains were, however, laid to rest in peace and amity, and all present lived to forgive and forget. Another instance of a different kind may be related. An old woman, given to tramping the Highlands, died at one end of our glen, and the people there having resolved to bury her remains at the other end, rather than in their own graveyard, the others determined to resist. On the day appointed for the funeral the latter turned out in force, and when about half-way up the glen they met the other party. Remonstrances were numerous, but it was evident that neither side was prepared to yield. Finally it was agreed, as a compromise, that the old woman's remains should be buried there, half-way between the two cemeteries, and at that spot, marked by a common slab of stone, the grave can still be seen.

Such instances as these were, of course, rare. The fact, generally speaking, is that Highlanders respected death and all that pertained to it with exceptional depth of feeling and solemnity. It was to them a serious message from beyond the bar. Perhaps the sharpest sting in it to Highlanders was the parting for ever with dear ones leaving never to return: "Cha till e tuilleadh." This the Celtic heart never fails to feel most keenly. And, correspondingly, the Celt has evinced peculiar interest in all ages and circumstances in the resting-place of the dead; for there:

" Beneath the rugged elm, that yew tree's shade,

Where heaves the turf in many a mouldering heap,

Each in his narrow cell forever laid,

The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep."

Chapter 10 |