Contents

Contents

BEING PRINCIPALLY

Sketches of Olden-Time Life in the Valley of the Great Glen of Scotland

WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO GLENMORISTON AND VICINITY

By ALEXANDER MACDONALD

INVERNESS

" Mar ghath soluis da m' anam fein Sgeul air ua laithean a dh' fhalbh "

—

Ossian

PRINTED BY THE NORTHERN COUNTIES NEWSPAPER

AND PRINTING AND PUBLISHING COMPANY, LIMITED, 1914

PRINTED AT "NORTHERN CHRONICLE " OFFICE INVERNESS

[iii] PREFACE

Few districts in Scotland can vie with Loch Ness-side for song and story. It is a land of poetry and romance, more particularly Glenmoriston, where bards sang for generations untold, and where seanachies never wearied of relating tales of the days of old. The Author of the following work is a native of this poetic country, whose privilege it was as a boy to listen with rapturous attention to those stories and songs, amidst scenes and circumstances congenial in many respects. In this book he has made an effort to repeat to others some of those stories and songs, and convey some of the sentiments and associations with which those voices from the olden time imbued himself.

While written in English the volume contains much Gaelic prose and verse, a considerable portion of the poetry, as also of the general contents, having never been published. The work is not one of documentary history to any serious extent; nor is it a bare narrative of the manners and customs, beliefs and practices, peculiar to the district under contribution. It is a weaving of all these latter and something more around the life of its people, from early times till a recent period, on lines typical of the life of the Gael throughout the Gaelic kingdom generally. Everything found of [iv] interest has been brought into service, with a view to reproducing as faithful and interesting a picture as possible of the Highland life of the past, not only on Loch Ness-side, but in the Scottish Highlands as a whole.

Whether the Author has succeeded in his efforts towards this end, he leaves his readers to judge for themselves. He is aware that the work has numerous imperfections. It is admitted that a few slips and some inaccuracies have, notwithstanding very careful reading of the text, escaped detection. But the Author craves to be allowed to plead that these may be considered masters of minor detail and nothing more; while he would wish it be remembered that the work was written bit by bit - and frequently at long intervals - during the spare hours saved from the demands of very active and busy conditions of life. He would also desire to state that the work is intended to be, to some extent at any rate, a pioneer effort, it being a life-long ambition with him to present the sentiments, associa tions, and elements generally of the Gaelic life of the Olden-Time in a form in which, he thinks, those must be put before the Highland people in order that their interest in their own national history may be revivified.

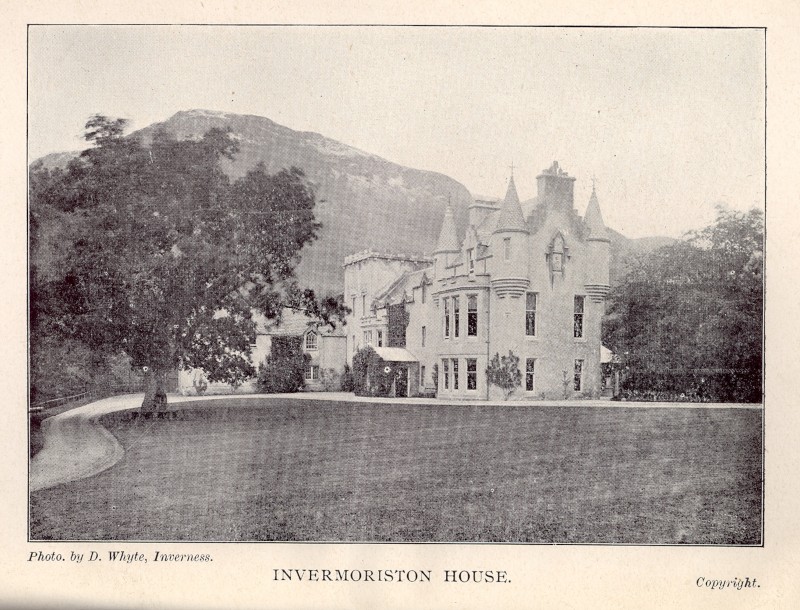

The Author wishes to make acknowledgment of obligations to the following for kind favours extended to him: To the Gaelic Society of Inverness, the Proprietors of the Northern Chronicle,Inverness, and The Caledonian Medical Society for permission to [v] quote freely from contributions by him from time to time to the Gaelic Society's "Transactions", the Northern Chronicle, and The Caledonian Medical Journal; to the Proprietors of The People's Journal and The People's Friendfor permission to reprint from certain articles already published in these publications; to Messrs David Bryce & Son, Publishers and Advert ising Contractors, 133 West Campbell Street, Glasgow, for permission to reproduce the picture of "Ewen MacPhee" (MacIain Series); to Mrs David Whyte, Inverness, for the picture of Invermoriston House, the frontispiece to the book; while the pictures on page 39 have been taken from the "Illustrations for Burt's Letters from the North of Scotland" and the one at page 196 from "The Penny Magazine" of the year 1835.

The Author would also acknowledge indebtedness to Dr William Mackay, Inverness, and Rev. A. J. MacDonald, Killearnan, for various helpful suggestions; and to "Urquhart and Glenmoriston", by Dr William Mackay, and "The Grants of Glenmoriston", by Rev. A. Sinclair, Kenmore, for information as to dates, &c.

A. McD.

Inverness, June, 1914.

[vi] CONTENTS

Preface iii

Introduction 1

CHAPTER

[1] INTRODUCTION

It is generally agreed that on the 16th of April, 1746, the date of the fateful Battle of Culloden, was sounded the death-knell of the old order of things in the Scottish Highlands. Up till then there had, in large measure, existed in Scotland what might practically be considered as two nationalities - the Lowland and the Highland or Gaelic - which had far less in common than is usually supposed, particularly by writers who do not make a special study of the domestic aspect of the country's history. Not only did the great bulk of the Highland people of the olden time, during many generations, speak exclusively a tongue different from that of their Lowland neighbours;the circumstances of their living, and their civilisation as a whole, were also very much of another kind. The Highlanders held beliefs largely peculiar to themselves, while their manners, customs, and rites differed widely from those of the Lowlanders. Indeed, at heart, the Highland or Gaelic nationality appears frequently to have contemp lated anything rather than quiescent partnership in the one consolidated Kingdom of Scotia. It is well known that the Isles had practically set up a kingdom of their own, and on various occasions made bold [2] attempts to increase their power in extent and authority. The great House of Clan Donald at one time dictated law and order throughout the West and North, made terms with Kings and Queens, and is believed to have held the destinies of the '' Half of Scotland'' in the hollow of its hand:

| Tigh is leth Alba | |

| Bha sud aig Righ Fionnghall, | |

| 'S ge b'e 'theannadh ri mharbhadh | |

| Cha b' fharmadach dha. |

says one of the bards. We quote from the same authority (Archie Grant, Glenmoriston) the following further reference to the Clan Donald possessions, which we think of interest in this connection:

| Aig gach linn mar a dh' fhalbh dhiubh, | |

| Dheth na Milidh le seanchas; | |

| B' ann diubh Art agus Cormaig, | |

| Siol Chuinn a bha ainmeil; | |

| Sliochd nan Collaidhean garga, | |

| Le 'n do chuireadh Cath-gailbheach [Gharrioch], | |

| 'S Domhull Ballach nan Garbh-chrioch, | |

| Rinn Tigh-nan-Teud aig leth Alba na chrich." |

These references are of no small importance when it is considered that " Tigh-nan-Teud " is still well known in the Pitlochry district, Perthshire, as the ancient land mark said to have divided Scotland into two halves, one of which would, of course, have been Celtic, or Gaelic Scotland, which confirms the tradition that the Mac Donalds held the "Half of Scotland and a House"; while it is freely admitted that they exercised leading influence and authority throughout the length and breadth of the Celtic nationality in Scotland, for many centuries. The memorable Battle of Harlaw, in 1411 - [3] the result of which was the first serious blow to Highland or Gaelic ascendancy - would seem to have been practically a bid by the Islesmen for at least independent, if not predominant, authority in Scotland. The effect of the engagement, however, did not, and could not make itself felt for a long time after. The seat of government was too far removed from the homes and haunts of the Highlanders to impress its discipline - such as it was - upon them; and there were few or no roads or means of access to, or intercommunication throughout, the country. Thus, Highland or Gaelic nationality flourished, and was by no means very extensively affected by the economic or political movements in Lowland Scotland, till the coming of the new era that followed the opening up of the country to Southern influences after the disturbance of the '45. The decline then of chief ship as what might be termed a national institution, the confiscation of properties, and the transference of possessions, in numerous cases into alien hands, conse quent thereon; also the settling down of Southern farmers, shepherds, and craftsmen in the country, brought about a condition of things which immediately began to strike at the old order. There was now no longer to be a kingdom within another in Scotia; and though there were two economies face to face, the stronger and less conservative brought with it a thousand and one influences calculated to directly promote, if not eventually to ensure, its survival as the more fit.

Yet the day of the ancient Highlander had not passed away. In the midst of great and essential changes, and in wonderful harmony therewith on the whole, Highland sentiment flourished, and, strange to say, absorbed many elements antagonistic to its own spirit and [ 4] character, which is most interesting as showing the remarkably absorbent qualities of the Highland mind. At the same time, many of the Lowlanders who came into the Highlands then became in time more Highland than Highlanders themselves. Thus, were it not for the depopulation of the country on a large scale, through emigration and other channels, the Highlands would probably still have retained their distinctive individual ity in comparatively large measure. If only the natural overflow of the people left the country, and that the others had been encouraged to settle down on suitable holdings, or small farms, Highland sentiment and nationality would not have suffered nearly so much as has been the case, while the evils of the past century and a half, and the greatly impoverished condition of the country at heart, which has resulted therefrom, for most would not have yet been heard of. In so far, however, as the people managed to live in their own way, they adapted the new order, as well as they could, to their conditions, while they succeeded in retaining much of their language, sentiments, customs, manners, and beliefs. But in all matters of this sort the governing factor is the daily bread.

When it is considered that, even yet, in many remote districts of the Highlands the native tongue is spoken habitually, and that the ways of the olden time are in evidence, it can be easily imagined that, let us say within some one hundred years back, or so, there was much to be heard and seen in the country that partook of the character of the old world in its entirety. The past fifty years, indeed, have witnessed greater changes in all parts of Britain and Ireland than possibly the preceding century or more. Tradition spoke with no uncertain [ 5] note, till within quite a recent time, of the ways and means of the days of old, with their:

Simple plan,

That they should take who have the power,

And they should keep who can.

the days of adventure and romance, while also of severities and hardships. It might be interesting to mention here that memories of, for instance, the period of Culloden were quite fresh in old people's minds till within a few years past. We have ourselves conversed with some to whom the event itself had been described by eye-witnesses. We remember, with vivid distinctne ss, one old woman relating the story of the battle, as told to her by a man who was engaged on one of the fields in close proximity to the scene of the fight. He detailed with minuteness all that he saw of the miserable engagement. He spoke particularly of the wretched cold of the day. The hail was lying deep on the ground just as "the battle commenced, and there was much sleet. He ceased work, and as he was approaching his house he could see the contending armies in grips. It was, he remembered, a time of great excitement while the conflict lasted uncertain; but that time was short, for the luck of the day was with the Redcoats, and the brave Highlanders quickly gave way in great disorder. Then,, the butchery which made the English infamous comm enced, and gave interested and disinterested alike to feel that their lives were, indeed, in danger. This same old person, when waxing eloquent over the bravery of the Highland host at Culloden, related with intense emotion the story, as told by the old people, of the hero Chisholm, from Strathglass, who was seen [6] performing exceptional deeds of valour during the fight. He was reported to have become temporarily mad, under the influence of a certain frenzy, which was believed to ward off death itself for a time. According to certain accounts, the Celts were subject to this wild spirit in battle - "Mire-Chath" - and to it was attrib uted their invincibility on numerous occasions. Chisholm, who was standard-bearer in his regiment, rallied his comrades repeatedly, and at length, finding himself practically alone, he literally cut his way through all and sundry to a small barn where his party had taken shelter. Setting his back against the door of the building, so that he could not be attacked from behind, he continued to cut down the enemy as fast as they came within the sweep of his claymore, and not until some seven bullets had got into his body did he fall down exhausted, and dead. This was the William Chisholm to whom his widow, Christina Ferguson, a native of Contin, composed one of the sweetest and finest elegies in the Gaelic language, the refrain to which is "Mo Run geal og" ("My fair young love"). Yet another tradition of the famous '45. There was in the district, whose history these pages more particu larly relate, an old black three-legged pot, somewhat conical in shape, in regard to which the following interesting legend was told. According to the prevail ing belief, it was in this utensil that were prepared for the royal palate of Prince Charles Edward Stewart, in the cave at Corry Dho, in Glenmoriston, such meals as the faithful men who so kindly befriended and so bravely protected him there, could, in their circumstances, provide for their illustrious visitor. The belief as to the identity of the pot was not confined to our own [7] and neighbouring districts; for it was well known that more than one interested in historical relics had already inspected it, while it was understood that offers for its purchase had also been made. It has since been exhibited, and there is little room for doubt as to the genuineness of its history. There lived till quite recently in our midst a man of the MacDonald clan who was third in direct descent from one of the Mac Donalds who were in the cave with the Prince; and he gave it as fact that it was in his family's possession from generation to generation, all along till a few years ago, when it fell into other hands. It is now in the posses sion of Grant of Glenmoriston. And tradition traces the connection of the pot with the MacDonald family still further back into the past. Ancient story tells that it came originally from Ireland; and there had been other two of the same kind, though of them no trace can now be found. But the one in evidence is believed to have been from the first associated in history with certain of the MacDonalds, who possessed Glenmoriston for centuries, as vassals of, and tacksmen under, the Lords of the Isles. There was no doubt as to its having been in the possession of a descendant of these Mac Donalds, known as "Alasdair Cutach", who was a famous hunter in his day. "Alasdair Cutach " had a son called John, who had a son Alexander, known as "Alasdair Buidhe." This Alexander is mentioned as certainly in possession of the pot, and he was one of the men who so nobly watched over the fugitive Prince at a time in the course of his wanderings when the fidelity and honour of the Highlanders of Scotland shielded him, as if by a miraculous providence, from his numerous enemies and pursuers. On one of the [8] nights the Prince was in the cave, this Alexander MacDonald had born to him a son, whom he called Charles, after his beloved though uncrowned King. Charles had a family. Three of the sons were called John, Malcolm, and Donald, respectively. Some of John's descendants are still in Glenxnoriston, while Malcolm was the father of the MacDonald Brothers, at one time so well and so favourably known as fleshers and agricul turists in Inverness. Donald occupied for some time a holding at Aonach, after eighteen years' occupancy of the inn there, at which Dr Johnson, on his famous sojourn to the Hebrides, put up for a night, and where he pres ented to the daughter of MacQueen, the then occupier, a copy of Croker's Arithmetic. Later in life he removed to Achnanconeran, Invermoriston, where he held a good holding till his death. He had a large family, one of his sons being Angus MacDonald, the man we have referred to as descended from one of the Men of Glenmoriston, and our own father, who died recently, ninety-seven years old, and of whose reminis cences, along with those of our mother, our history largely consists.

Though the Highlands as a whole had, about the time we have fixed, arrived at a parting of the ways, as regards the olden world, and though modern influences were fast making converts among the people, there was yet an important section of them who lived in the past, with all its weirdness, its peculiarities, its idealism, and its romance. These represented a world of their own - a rapidly narrowing borderland the history of which it would prove most interesting to possess at some length. Such conditions of living, or such circumstances, shall never be again. It was a state of existence which, while [9] partaking freely of very rough elements of civilization, yet had many redeeming features in its general economy. What though there was little circulation of money ; there was none of the care and worry which the posses sion of it brings in its train, and there was, upon the whole, little real poverty and no starvation, while there was little " wringing life out to keep life in." What though the fashions were not studied; the people were well clothed, and in general there were good physiques. What though there was neither much style nor cerem ony; these were not missed. There was, again, more time to enjoy existence, and to taste of the sweet springs of being close to the heart-throb of Nature—what we must get back to once more, while also making the proper use of the amenities of civilization, if we are to live as we would appear to be intended to do. This is, roughly stating it, the sense in which the past was better than the present is. In the olden time they wanted much they did not require, and had conseq uently not to pay for; in the present we possess much, but pay a heavy price for our advantages; and life has admittedly become too much of a sacrifice and a struggle. Excessive ambition is the minotaur of modern existence. The old people had perhaps too much time to think, and that was one of the principal causes of their idealism. Purely material things were not everything with them; the spirit side of being occupied their minds a great deal, and this made them intuitive rather than acquisitive. We are now too materialistic. We have thrown nature out of our world, and taken in a thousand and one second-hand substitutes. Perhaps, it may have been by way of making effort to identify their idealism with their life that the simple [10] people of the olden time were somewhat superstitiously disposed. Their beliefs and customs were possibly reflexes of their inward ideas. In any case, they moved and had their being on a comparatively high plane.

The life of the Scottish Highlander - at any rate within the period we embrace - consisted in generous measure of solid pleasure all round. He combined sport and pastime with his daily work, and he enjoyed practica lly unalloyed domestic contentment. In the winter season, when little work required to be done, music, dancing, story-telling and similar other intellectual exercises helped to while away the time. When Spring came round, with its returning life and hopefulness, the Highlander's lines were in such pleasant places as rendered them almost a privilege; and during Summer and Autumn his circumstances were always such as the wealthier section of the public of to-day pay thousands of pounds to get a transient glimpse of.

The Highlander's life still possesses elements of a variety all its own - elements that are at once interesti ng, educative, and formative. From the beginning to the end of the year it is one continuous round of varying experiences, most of them, perhaps, as natural to mank ind as any could be. It will, of course, be understood that we refer here more especially to natural surroundi ngs and facilities conducive to happy living. That the Highlanders have not, as a body, made the most of these conditions is only too true;but that as a fault is chargea ble entirely to themselves. The conditions have always been there in large measure, and such as compared with which the possibilities of town life - say in the case of an ordinary working man - are "as moonlight unto sunl ight, or as water unto wine". A little judicious, [11] well- directed effort of mind and body on the part of the Highl and peasantry themselves, in the direction of housebuilding and relative amenities, would have put them on a level with the average middle-class people of the industrial centres at any rate, including, of course, for the former such assets as moral surroundings, good health, peace of mind, duration of life, and similar considerations. The great shortcoming of the High landers has been that they have failed to recognise sufficiently that the world around them has moved for ward. They have been content to sit inactively within a circle, rather indifferent to the important fact that the circle has been changing its position. Notwithstanding much treatment that was disheartening at the hands of some landlords, they themselves failed, at a critical juncture, to recognise fully their obligations as industri ous citizens of society and the nation. At the same time, nationality and sentiment came to be discarded as sinful; the Highland mind taking refuge in a quagmire of "religious impossibilities and inconsistencies, which have since rendered the people as a whole not a little incapable in many ways - in a word, more or less unfit to live and afraid to die. The world of the Gael has always been too much within himself. He must learn to "cast his bread upon the waters" and "believe in the larger hope". Progress requires ''a give and take'' - a commingling of thought and action - full individual development for the betterment of all.