"Story and Song from Loch Ness-Side"

|

|

By Alexander Macdonald

|

|

Chapter II

|

| How People Lived |

[35]

We should like now to make a few observations in regard to the economic conditions prevailing in our district in the past, from time to time, and we fear, frankly speaking, that, in this connection, its history is not a continuous chapter of rapid and steady progress. In the darker ages the people existed practically by the chase and wild berries, and, to at least a certain extent, led the nomadic life. We are disposed to believe, how ever, that, at anyrate early in the Christian era, the cultivation of the land - most probably in small patches - was more or less general, and that the people, as a whole, had arrived at the pastoral stage of their economic progress.

The industrial spirit, in so far as the creation of resources is concerned, has not been particularly characteristic of Highlanders. Improvements on and extensions of primitive means and methods they certainly did from age to age bring about; and for centuries back farming has existed. But, as a people, they confined themselves to narrow limits in the cultivation of the ways and means of life, and they at no time exercised extensively the commercial and speculative elements in civilization.

Pennant quotes Boethius as relating "that in his time Inverness was greatly frequented by merchants from Germany, who purchased here the furs of several sorts of

[36]

wild beasts, and that wild horses were found in great abundance in its neighbourhood; that the country yielded a great deal of wheat and corn, and quantities of nuts and apples". And he goes on to say "At present [about 1770] there is a trade in the skins of deer, roes, and other beasts, which the Highlanders bring down to the fairs. There happened to be one at this time: the commodities were skins, various necessaries, brought in by the pedlars ; coarse country cloths, cheese, butter, and meal; the last in goat-skin bags; the butter lapped in cawls, or leaves of the broad alga, or tang; and great quantities of birch wood and hazel, cut into lengths for carts, &c. which had been floated down the river from Lough Ness." Burt, some time previously, mentions four or five of these fairs as held yearly in Inverness. These references furnish a peep at the economic and commercial conditions prevailing on Loch Ness-side, more or less for centuries. There the ways and means of living consisted substantially of the agri cultural and the pastoral combined; but the land did not always receive the best of treatment, and the crops produced were not of a high order. There was, however, considerable attention paid to cattle and their produce. During summer the cattle were fed on the hill pastures, where certain members of the families tended them, and made the butter, cheese, and crowdy, on which the people largely subsisted. This was the ancient and interesting institution of the shieling ("an airigh"), which for long entered prominently into Highland economics.

In Glenmoriston, for instance, previous to the intro- duction of the big sheep from the South, Corry-Dho, to the north of the river Do, was occupied as shielings by families fromthelowerglen, and even from

[37]

GlenUrquhart. Besides making butter and cheese, they planted cabbages, and latterly potatoes, in plots of ground made into ridges and called "lazybeds" and they helped themselves to game from time to time by way of supplementing their larders. The removal to the shiel-ings took place generally in March and April, but some of the people returned to the low grounds in June, the others following towards the end of the open season. The grazing was common to all the occupiers.

There were craftsmen in the district - some of them from very early times - such as blacksmiths, millers, masons, carpenters, shoemakers, and tailors, and they would appear to have been getting something to do from time to time.

Soon after the '45 the Forfeited Estates' Commis sioners established a Factory at Invermoriston, by way of meeting the poverty and want brought about at the time, principally by the banishment of some seventy bread-earners to a foreign strand. A number of men and women obtained employment at this work, but about the year 1791 it was discontinued. The buildings, which are situated near Invermoriston mansion, have since been used as the Home Farm steading. A field near is still known as "Pairc-an-Fhactorie" and "Coill'- an-Fhactorie" is adjacent.

There was, in the olden days, important traffic in timber. Great rafts of felled trees were from time to time floated down on the rivers from the higher reaches of the glens. This was known as "am ploddadh" and gave labour to a number of men. In summer there was, at a later time, the "barking" traffic - "An cartadh" - which provided work for men, women, and young persons of both sexes; and in winter there was frequently some planting done.

[38]

Smuggling might practically be considered an industry about eighty or ninety years ago. There were purchases of barley from places as far townward as Dochfour, and certain families carried on a brisk trade in the line. The business - for business it actually was - had risks and dangers attached to it; but it was exciting, lively, not a little romantic, and by no means unprofitable.

Employment was frequently obtained in connec- tion with road-making, and such improvements; and there was latterly service with the proprietor and the Larger farmers. We have heard of as many as sixty shearers being at work on one field in the harvest time, when hooks were in general use, and before scythes became popular. Labour was, of course, at all times cheap, the wages for men's services, when in later years considered good, amounting to about 1s 6d per day.

The advent of the big sheep to Glenmoriston was not a matter of the very long ago. About the first of those to come were some placed in Corry-Dho, at the top of the Glen. They were introduced from the South by Major Alpin, one of the Glenmoriston family, a brother of Captain Allan of Inverwick, and uncle of Colonel John Grant of Glenmoriston, great-grandfather of the present proprietor. The first shepherd who came to the Glen from the South was Ewart to name. He is supposed to be buried at Bair-an-Tom-Buidhe. He had a son who died at Allt-na-Meirleach, and who is buried at the same place. Major Alpin erected a large sheep fank, which was probably the work of Ewart. It is said to be still visible in ground-plan, the design in outline being easily traceable.The Major lived at the time - or soon

[39]

afterwards at Borlum, GlenUrquhart. It was he who also placed the first big sheep on Inver- moriston grounds, which extended to Alltsaigh. He employed for his head shepherds, or managers, one Peter MacDonald, from Inverwick, whose descendants

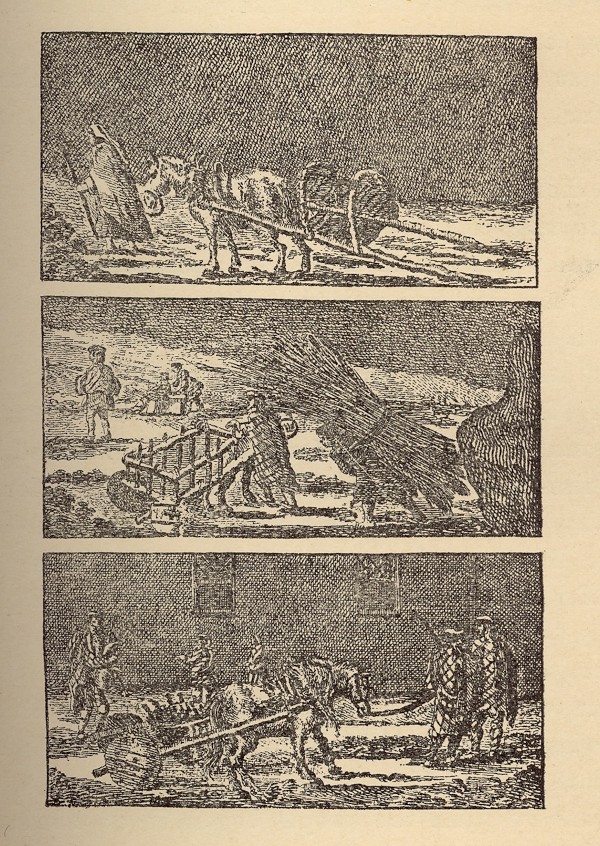

[Illustration]

settled at Bail-an-Tom-Buidhe, and a man named Muir, who was a native of Ayrshire. Muir's descendants are still numerous in Glenmoriston and Stratherrick. There is a tradition in the families that he knew Robert Burns personally.

afterwards at Borlum, GlenUrquhart. It was he who also placed the first big sheep on Inver- moriston grounds, which extended to Alltsaigh. He employed for his head shepherds, or managers, one Peter MacDonald, from Inverwick, whose descendants

[Illustration]

settled at Bail-an-Tom-Buidhe, and a man named Muir, who was a native of Ayrshire. Muir's descendants are still numerous in Glenmoriston and Stratherrick. There is a tradition in the families that he knew Robert Burns personally.

[40]

Major Alpin was a distinguished member of the Glen- moriston family, and was at one time well known in Inverness. He occupied a house at the Citadel, where he established a hemp factory. He entered the Town Council in 1785, and became a Bailie in 1802, and a Deputy-Lieutenant for the County in 1811. His name is perpetuated in Grant Street. His wife was a daughter of Alexander Shaw, agent for the Bank of Scotland, Inverness, who also managed the factory founded at Invermoriston in the year 1756. Major Alpin had a family of sons and daughters, and left numerous descendants.

Captain MacDonell of Aonach, about the same time, placed sheep on the south side of the Moriston river, on to Loch Clunie and Craig Nathrach, also on the south side of Loch Luine, on the march of the Glenmoriston estate. The shepherd appointed to take charge was John MacDonald, son of Ewen MacDonald, and he lived below an Doire-Mhor, on the south side of the Moriston, half-way between Loch Clunie and Bun-Luine. Ewen MacDonald was a son of Ewen Mac Donald, at one time of Inverwick ("Eoghann Buidhe"). John MacDonald's assistant was Alex. Macrae, a native of Kintail. He lived at Bun-Luine. His son was afterwards shepherd at Aonach, and lived at Inverwick, where both father and son died. They are buried at Bair-an-Tom-Buidhe.

Little by little the people began to do better with their holdings, and, in later years, there was improve- ment all round. With the repeal of the corn laws and other economic movements, food became cheaper, and labour began to be better paid. The advent of the shooting tenant also caused the distribution of money

[41]

among the people; so that between the produce of their land and their earnings from service, here, there, and elsewhere, from time to time, there was always something in hand, and there has now for long been a fair living for all.

As to the important matter of food, there is no reason to suppose that the people of our district fared at any time very badly, except, as certainly happened occasion ally, when overtaken by hard times; and then they had, in some cases, to bleed their cattle to tide over very trying periods. Those severe circumstances were brought about for most by bad seasons, poverty of seeds, or by feuds and forays, and the fact that all outlying districts were commercially isolated. On the other hand, there is every indication that, though the fare was perhaps of a somewhat rough and ready character, and though there was not great variety, yet there was a fair supply of it. The simple life, of course, prevailed. Within the past three hundred years or more meal and milk have been well in evidence, and the introduction of the potato, early in the eighteenth century, very materially added to the means of living; while cabbage, in various forms, appears to have been an important article of diet from a time far older than is usually supposed. Access to the hills and the waters has not, at least for a long period now, been free; but there is much reason to suspect that most of the people continued long to supplement their ordinary stores from these sources:

| " Breac a linne, |

[42] "A trout from a pool, |

| 'S fiadh a fireach, |

A deer from the hill, |

| 'S maid' a coille, |

And a tree from the forest, |

| Meirle as nach do ghabh |

Are thefts of which no |

| Duine riamh naire." |

Man was ever ashamed." |

Within more recent times most families have always, been in a position to kill a sheep or a cattle beast, and possess themselves of a supply of herrings, for winter consumption. Tea, and the more refined articles of diet, were coming gradually into every day use. Whisky has been known as a beverage for probably a century and a half or so, and previous thereto beer,. wine, and brandy were fairly common.

In the matter of dress the people's requirements, from the earliest times till a comparatively late period, were simple. No doubt the first attempts in all cold climates were from skins. When clothing appeared it would have consisted largely of a covering which the male learned to kilt roughly about him, and by which the woman covered herself pretty much from head to foot. These experience has modified and improved into their present day proportions and forms. We cannot perhaps do better in the way of giving an intelligent idea, of the dress of the ancient Highlanders generally than submit the account of dress in the Isles in Martin's description, written during the early years of the eighteenth century, and which we quote from the "Transactions of the Iona Club", Vol. I, Part II. It fixes a history of the subject at an important period in its development:

"The first habit wore by persons of distinction in the islands was the leni-croich, from the Irish word leni, which signifies a shirt, and croich, saffron, because their shirt was dyed with that herb...... It was

[43

]

the upper garb, reaching below the knees, and was tied with a belt round the middle; but the islanders have laid it aside about a hundred years ago. They now generally use coat, waistcoat, and breeches, as elsewhere, and on their heads wear bonnets made of thick cloth, some blue, some black, and some grey. Many of the people wear trowis: some have them very fine woven, like stockings of those made of cloth; some are coloured, and others striped: the latter are as well shaped as the former, lying close to the body from the middle down- wards, and tied round with a. belt above the haunches. There is a square piece of cloth which hangs down bsfore..... The shoes anciently wore were a. piece of the hide of the deer, cow, or horse, with the hair on, being tied behind and before with a point of leather. The generality now wear shoes, having one thin sole only, and shaped after the right and left foot; so that what is for one foot will not serve for the other."

'' But persons of distinction wear the garb in fashion in the South of Scotland."

" The plad, wore only by the men, is made of fine wool, the thred as fine as can be made of that kind; it consists of divers colours, and there is a great deal of ingenuity required in sorting the colours, so as to be agreeable to the nicest fancy...... Every isle differs from each other in their fancy of making plads, as to the stripes in breadth and colours. This humour is as different through the mainland of the Highlands, in so far that they who have seen those places are able, at the first view of a man's plad, to guess the place of his residence...... The plad is tied round the middle with a leather belt; it is pleated from the belt to the knee very nicely. This dress for footmen is found much easier and lighter than breeches or trowis."

"The ancient dress wore by the women, and which is yet wore by some of the vulgar, called Arisad [Earasaid], is a white plad, having a few small stripes of black, blue, and red. It reached from the neck to the heels, and was tied before on the breast with a buckle of silver, or brass, according to the quality of

[44]

the person...... The plad being pleated all round, was tied with a belt below the breast; the belt was of leather, and several pieces of silver intermixed with the leather like a chain. The lower end of the belt has a piece of plate, about eight inches long and three in breadth, curiously engraven, the end of which was adorned with fine stones, or pieces of red coral. They wore sleeves of scarlet cloth, closed at the end as men's vests, with gold lace round them, having plate buttons set with fine stones. The head-dress was a fine kerchief of linen strait about the head, hanging down the back taper-wise; a large lock of hair hangs down their cheeks above their breasts, the lower end tied with a knot of ribbands."

Captain Burt, in his letters from the North, already referred to, describes the dress of the Highlander, as he saw it throughout Inverness district, during the first half of the eighteenth century, on substantially the same lines; but he mentions additional in regard to woman's dress that " the ordinary girls wear nothing upon their heads until they are married or get a child, except sometimes a fillet of red or blue coarse cloth, of which they are very proud; but often their hair hangs down over the forehead, like that of a wild colt; "also that" if they wear stockings, which is very rare, they lay them in plaits one above another, from the ankle up to the calf." Pennant, towards the latter half of the same century, follows with a practically similar account; but his reference to the kilt is worth quoting. He says: "The fillebeg,

i.e.,little plaid, also called kilt, is a sort of short petticoat reaching only to the knees, and is a modern substitute for the lower part of the plaid, being found to be less cumbersome, especially in time of action, when the Highlanders used to tuck theirbrechan intotheir girdle.Almost all have a

[45]

great pouch of badger or other skin, with tessels dang ling before. In this they keep their tobacco and money."

It would appear from the foregoing references that the trews was, at one time at any rate, the principal article of the dress of the ancient Highlanders, and this is in no inconsiderable measure confirmed by Sir John Sinclair, who, writing on the subject in 1796, indicates that the dress of the well-to-do people and of the more respectable class was the trews and plaid, both made of chequered stuff.

It is within living memory that most men in our district wore the kilt, short jacket, and plaid, with a broad cloth bonnet, and sandals made from hides and skins. Only a few of the better-to-do wore trews, and these only on occasions. It is also still within memory that the principal article of woman's outer garment was the earasaid - which served much for head and body dress - with sandals or light shoes and stockings for foot cover. Boots are a recent invention. For a long time at least plaiding formed a principal cloth for general use. Latterly suits were made of it for men, and for women petticoats - "cotachan ban" or "cotachan gorm" - which came to be worn very much, along with linen or cotton bodices - "bedgowns" - as they were called. It is certain that at one time white linen shirts, made substantially from home-grown flax, were common. Skirts and short coatees - the skirts of the poorer class made of wincey - "drogaid" - came about the same time into use for the women, and the older ones wore starched mutches on their heads. Until they married, the young girls wore nothing on their heads but a mere band - the snood, latterly the "bandeau".

[46]

The people seem to have made most of their clothes at their own firesides, the women doing the carding and spinning, except that the weaver manufactured the web; and when that was finished, the tailor, who went from house to house, came round and tailored the cloth. The women made most of their own dress, and some men were apt shoemakers; while among them were not a few who could also ply the needle. But theirs was generally the tailoring of their own under-clothing, when such was in use.

As regards house accommodation and furniture, the people's wants, until quite a recent date, were also characteristically simple. The earliest inhabitants most probably dwelt in caves. The first attempt at house- building was undoubtedly the hut, which consisted of wattles and turf. In course of time a hole (the

"arias") was made in the top of the hut for letting out the smoke, and still later, one in the side for letting in the light. A very representative idea of what the houses in the Gaelic-speaking districts of Scotland were for a long time may be gathered from what Pennant says as to how he found them in Perthshire about the year 1770: "The houses in these parts began to be covered with broom, which lasts three or four years; their insides mean and scantily furnished; but the owners civil, sensible, and of the quickest apprehensions". And, further, he describes them as

"in small groupes, as if they [the Highlanders] loved society or clanship; they are very small, mean, and without windows or chimnies, and are the disgrace of North Britain, as its lakes and rivers are its glory". We find also in one of the notes to No. xx. of "Burt's Letters" (Jamieson's edition), a pretty full description of Highland houses

[47]

at a somewhat later date. The note, which is from " Garnett's Tour", says, in reference to a Highland town: "Their cottages are in general miserable habi tations; they are built of round stones without any cement, thatched with sods, and sometimes heath; they are generally, though not always, divided by a wicker partition into two apartments, in the larger of which the family reside: it serves likewise as a sleeping-room for them all. In the middle of this room is the fire, made of peat placed on the floor, and over it, by means of a hook, hangs the pot for dressing the victuals. There is frequently a hole on the roof to allow exit to the smoke, but this is not directly over the fire, on account of the rain, and very little of the smoke finds its way out of it, the greatest part, after having filled every corner of the room, corning out of the door, so that it is almost impossible for any one unaccustomed to it to breathe in the hut. The other apartment, to which you enter by the same door, is reserved for cattle and poultry, when those do not choose to mess and lodge with the family."

While these observations applied to Highland houses in many places, on Loch Ness-side, as in some other districts not too far from centres, the houses were somewhat better. The cattle in the same room as the people, if the arrangement ever existed there, must have been in the long, long ago, unless as an odd case. The fire in the middle was there, at any rate, also a thing of far back ages; as, since many years there has been, in the very oldest houses, a strong stone parti tion behind the fireplace and on to the outside door, with a sort of hanging chimney ("simileir-crochaidh") built over the fireplace, which confined the smoke and guided it outside, in most cases as successfully as by an

[48]

ordinary chimney. On Loch Ness-side the "black house" of the 18th and much of the 19th century was constructed on fairly good lines. Stones took the place of wattles, and the thatch, which was, to begin with, entirely of divots, called "sgrathan", was improved by a covering of brackens, or heather, or broom over the turf, secured by hazel wands, called " na sguilb." The couplings were a certain crooked form of tree from the forest, called "na suidheachan", or "na maidean- ceamhail." The top ridge of the house - a long caber resting on the couplings where they were fixed at certain spaces - was called "an druim-ard," and the side beams which supported the rafters of the roof -

''na cabair" - were known as "na sailbhean". The joints; in this timber were all "nailed" by long wooden pins, called "na cnagan." Latterly, of course, better houses still made their appearance in the district, as elsewhere in the Highlands. A commendable taste for conveni- ence, and for greater comfort and cleanliness, was making itself felt even among the poorer people, and the better-to-do have enjoyed good, comparatively modern houses for many generations. The "black houses'' of the olden time were not good houses by any means, but were not always uncomfortable, and they were wonderfully healthy and warm.

Furniture and furnishings scarcely existed at one time except among the better class. The people's bedding in the long ago consisted of rushes, heather, and brushwood; while the seating accommodation was usually of stone or turf. The vessels used for dietary purposes were principally made by the people themselves. Wooden basins and kegsweremuchinuse.The fuel consisted almost

[49]

entirely of timber and peat, and the lighting was by fir torches, before home-made candles and the cruizies came into use, and indeed occasionally afterwards. Not so very long ago Glenmoriston was described as:

| "Gleanna min Moireasdain, |

"Fair Glenmoriston, |

| Far nach ith na coin na coinnlean" |

Where the dogs won't eat candles" |

because the candles were not there. All this may be said to have given way, some time ago now, to the more modern improvements of our own age, the only solitary survival being the fuel.

All outlying districts suffered much and long from the want of means of communication. Till within less than some two hundred years ago there were practically no roads, and transport on land was mainly by panniers - rough baskets or creels - on horseback, and by sledges (which preceded the introduction of wheeled vehicles, and were much in use), there being only mere paths, which generally lay along the hill-tops for greater safety from attack or ambush. General Wade's roads were the first scientific attempt in that direction, and they were a mighty impetus to civilization. Truly can it be said - illogical as the expression may be: "Had you seen those roads Before they were made, You would lift up your hands And bless General Wade."

On Loch Ness-side travelling or transport facilities were not better than elsewhere in the Highlands. As matter of fact, there was little need for such, as communication

[50]

with the outside world was on a limited scale at most. Packmen came round with most of the odds and ends required by the common people, and they brought also news of the outside world, which were listened to and afterwards discussed with absorbing interest. Between the commercial centres and the mansion houses, after the completion of the high-roads, goods were carried by a regular service of horses and carts, driven by "carriers", whose adventures sometimes were of a stirring character. There was a postman once a week between Glenelg and Fort Augustus. He left Glenelg in the morning, took his dinner in the inn at Aonach, and crossed the hill to Fort Augustus, returning the same day to Aonach, where he put up for the night. Another postman travelled between Fort Augustus and Inverness, and appears to have made three journeys per week between these points. The postmen had many a weary, cold tramp, and many an exciting experience. One of the last of them, who travelled twice or three times a week between Drumnadrochit and Fort Augustus, about fifty years ago or so, called "Am Posta-Ban" ("The Fair Postman") - Stoddart to name - composed a rather interesting song, which we have pleasure in subjoining:

| Fonn: —Faill-ill-o ro-bha hi, |

|

| Gum beil m' inntinn fo phramh ; |

|

| Bho 'n chaidh mhaileid air mo dhruim, |

|

| Dh' fhalbh mo shunnd 's mo chiall-gair'. |

|

| 'N uair bhios each na 'n cadal suain, |

|

| Air an cluasaig gu blath ; J S ann bhios mise gu fliuch fuar |

|

| 'Fiachainn cruaidh air an t-sail. |

|

| [51]

Rathad fada, carach, fiart', |

|

| Tha e cianail mu

'ntraitli; 'S ann air srac an da uair dhiag |

|

| 'Dol a thriall ri Portchlar. |

|

| Coille dhluth air gach taobh, |

|

| Sneachda ghluin, cathadli ban ; Gaoth a' sadadh ri mo chluais,— |

|

| 'Nochd nach truagh leibh mo chas ? |

|

| 'N xiair ruigeas mi Tigh Iain-Mhic-Shim, |

|

| Bi'dh 'n ceol binn ri mo chluais; Abhainn Mhoireasdain na still,- |

|

| ;S chluinnte miltean a fuaim. |

|

| Theid mi ; n deigh sin air ino chuairt |

|

| Seachad suas an Tigh-Ban;

'Sgheibh mi

'm Postmasterna 'shuain, |

|

| Air a chluasaig gu blath. |

|

| Ruigidh mi 'n sin Creag-an-Uird, |

|

| Frasan dlutli a' tighinn orm ; Gus an ruig mi leth mo chiirs' |

|

| Bi'dh mi dliith 'deanamh lorg. |

|

| Ruigidh mi 'n sin Tigh-a'-Chaochain, |

|

| 'E 6 ! gur faoilteach iad ann ; Eiridh Iain 's e gun ghruaim, |

|

| JS bheir e nuas dhuinn an dram. |

|

| Theid mi sin air mo cheum |

|

| Seachad Leini le srann ; Gus an cuairtich mi ; n t-Sroin, |

|

| ;Mhan am Borlum na m J dheann. |

|

| Cha 'n e 'n samhradh is fearr, Oidhche bhlath 'n eallaich mhoir; |

|

| M' fhallas dluth 'falbh na smuid 'Call mo shugh as gach por. |

|

| 'Sged a thigeadh rothadh liath, |

|

| ' S uisge chuireadh sliabh air snamh ; |

|

| Cha 'n fhaod mise dhol fo dhion Dh' aindeoin sion thig a mhan. |

|

| [52]

Cuid a their gu bheil mi fior; |

|

| Cuid gur briag tha mi 'g radh; Saoilidh neach a bhios na thriall, |

|

| Nach tig crioch air gu brath. |

|

The "Posta Ban's" predecessor was known as "Am Posta Ruadh". His district embraced the whole dis- tance from Fort Augustus to Inverness, and he slept a night at Drumnadrochit on the way.

With the advancing times have come horse and machine, and steamboat and motor services, which still continue and flourish. For at least 150 years or so Glenmoriston has enjoyed the convenience of at least two inns - one in Upper Glenmoriston and one at Inver- moriston. Probably the oldest in the Glen was the inn at Aonach, a place now called "Achadh-leitheann" ("Broadfield"). It was in full swing in 1773, the year of Dr Johnson's tour to the Highlands, and, as is well known, he lodged in it on his way to the Isles. It was built of loose stones, wattles, and turf, and contained two beds. The then landlord was MacQueen, and the famous Doctor, as is elsewhere mentioned, gave the young daughter of the house, whom he found not at all badly educated, a small book on arithmetic as a parting gift! This inn at Aonach was tenanted for about eighteen years afterwards by Donald MacDonald, our own grandfather; and our father, who died recently, distinctly remembered "the auld hoose". There is mention of there having been about the same time an inn at Allt-Ghoibhneag, not far from Invermoriston House, where "Patrick Dubh," the laird of the period ( 1786-1793), used to treat his friends occasionally, among whom he was not too proud to include his own tenants.

Those old inns would seem to have been

[53]

replaced by the inns at Torgyle and Invermoriston respectively. In the past interesting associations attached to inns, and in Glenmoriston, as elsewhere, they had their songs and their stories of sorrow, of love, and of joy. With Torgyle inn is associated a version of the famous story which tells of a horse having on a certain occasion eaten an English trooper who was taking the way, and who had been put to sleep in the stable; the only foundation for the story being that the trooper's top-boots were found in the manger after the wearer had quietly disappeared. This inn was long tenanted by a family of MacDonalds, who, after a time, removed to Strathglass. We have come across a rather pretty love-song composed to one of the daughters of MacDonald, which we consider well worth giving here. Descendants of those MacDonalds are still traceable in these districts. The song is known by the name of "Smebrach 'Thorra-Ghoill"("The Torgyle Mavis"), and makes pleasant reading. We have failed to identify the author, and the composition is included in only one collection - "An Duanaire" - so far as we know, and from which we quote as follows:

| Tha smeorach bhinn |

|

| Ann an Torra-Ghoill, Fhuair urram ciuil |

|

| Air gach eun 's a' choiir, A maduinn Cheitein, |

|

| JS an driuchd ag eirigh, 'S tu thogadh m' eislein |

|

| 'N uair bhithinn trom. |

|

| A smeorach thaitneach, |

|

| Shlatach, dhonn, Gur neo-lapach |

|

| Do dhreach is t-fhonn; |

|

| [54]

A reir mo bheachd-sa Gur tu an tearc-eun, |

|

| A measg ealtuinn |

|

| Nam preas 's nan torn. |

|

| An uair a sheinneas |

|

| Tu 'n ribheid reidh, Bi'dh pronnadh luthor |

|

| An dluths nan geug; Coireal sunntach, |

|

| Gun sas, gun tuchadh; Gun eisd gach duil |

|

| Hi clia-lu do mheur. |

|

| Gur iad mo dhuraehd |

|

| ;S mo smuaintean trie, ; Bhi goid gu cuirteil |

|

| Gu bruach do nid;

'S na meangain uror, |

|

| Fo dliuilleach chubhraidh— Tha bias an t-siuoair |

|

| Air barr do ghuib. |

|

| Ach, ma dh' fhaodas mi, |

|

| Theid mi shealg, 'S gheibh mi baolum ort, |

|

| Gar am marbh; Bi'dh mi le cuirteis |

|

| Ri t-uchdan dluithte, 'S mo bhilean iompaicht' |

|

| Ri muirn gun cheilg. |

|

| Gur iomadh oidhche |

|

| Thug mi gun lochd, Air ti do chaoimhneis, |

|

| Air sgath nan cnoc

;

O ! eunain uasail, |

|

| Is eibhinn gluasad, Air feadh nan cluaintean, |

|

Gun ghruaim, gun sprochd. |

|

| [55]

Ma tha foirfe |

|

| An eun fo 'n ghrein, Tha i taisgte |

|

| An glaic do chre-s'; Gun chron ged dh' iarrt' e |

|

| Na d'chebl no t-fhiamhachd, 'S gach deagh bhuaidh

'giathadh |

|

| 'S a' chliabh gun bheud. |

|

| Ach ma dh' fhalbhas |

|

Tu uainn air chuairt, As do dheigh-sa |

|

| Cha bhi mi buan; 'S e Coire-Dhodha, |

|

| Mo ghleannan comhnuidh, Am bun nam mor-bheann |

|

| Is boidhche snuagh. |

|

| A bhrigh nach bard mi |

|

| Chur dhan an ceill, Gach buaidh tha 'fas ort |

|

| Cha tarr mi 'n seinn; Lag mo Ghaidhlig, |

|

| Is mheath mo chaileachd— Cha 'n iul domh aireamh |

|

Da thrian de d ; bheus. |

|

| O J n tha m' inntinn |

|

| Air brigh an f huinn; |

|

| 'S i Heni Dhomhnullach |

|

| Da ; n d' rinn mi J n t-oran— Nighean an asdair |

|

| Tha

'nTorra-Ghoill. |

|

After these MacDonalds, Duncan MacDonald, an uncle of our own, and his family, became the occupants, and remained in the place for years. This inn has for some time been closed as such, the old building having been

[56]

replaced by a new one,which is being used for most as a. summer residence for visitors. Tenants of the Invermoriston inn were successively: Fall, Bayne, Hossack, MacGregor, Campbell, Davis; and the present tenant is Mr Kyd. How all those families came to love the place and its people is a delightful sentiment to dwell on.

A vast change has taken place in the district. Things would seem to have shifted from one end of the pole to the other. In many respects the conditions of living in the olden time were unmistakably much worse than in the present day; in others considerably better. The numerous amenities which such as make an effort nowadays have at their disposal were, not so many years ago, not looked for at all among the common people, and even the better-to-do class did not always enjoy anything approaching the style and grandeur that have since come to be generally considered absolute necessities. And what though the "graddan" and the ''quern'' were here and there in evidence till a comparatively late time; they served their day, and there was considerable happiness notwithstanding the absence of many of the facilities and advantages that are now so common.

afterwards at Borlum, GlenUrquhart. It was he who also placed the first big sheep on Inver- moriston grounds, which extended to Alltsaigh. He employed for his head shepherds, or managers, one Peter MacDonald, from Inverwick, whose descendants

[Illustration]

settled at Bail-an-Tom-Buidhe, and a man named Muir, who was a native of Ayrshire. Muir's descendants are still numerous in Glenmoriston and Stratherrick. There is a tradition in the families that he knew Robert Burns personally.

afterwards at Borlum, GlenUrquhart. It was he who also placed the first big sheep on Inver- moriston grounds, which extended to Alltsaigh. He employed for his head shepherds, or managers, one Peter MacDonald, from Inverwick, whose descendants

[Illustration]

settled at Bail-an-Tom-Buidhe, and a man named Muir, who was a native of Ayrshire. Muir's descendants are still numerous in Glenmoriston and Stratherrick. There is a tradition in the families that he knew Robert Burns personally.