"Story and Song from Loch Ness-Side" |

| By Alexander Macdonald |

| Chapter I |

| Glenmoriston: Its Peoples and Possessors |

[12 ]

Loch Ness ! The name calls up a thousand and one associations hallowed by countless memories. There it lies, fondled by towering mountains and heath-clad hills ; and, if it could speak, what a story it could tell! As to how it came there is an interesting geological question - "only that and nothing more"; but tradition tells us with the utmost confidence that it had its beginning under the following circumstances: In the far back times of old, the valley of Loch Ness, like many other places, contained a well whose waters were of great virtue. This well was covered with a stone slab, and it was imperative that this slab should be placed in position over the well after it had been drawn from - more parti cularly before nightfall. There was a prophecy to the effect that if this simple duty was overlooked, even for once, the waters of the well would spread over the valley, and destroy everything there. For long, long, all went well; but an occasion came round when a woman, hearing the cry of her child, whom she had left at her fireside, hurried back, forgetting all about the stone-slab, and leaving it by the side of the well. Immediately the waters poured out, causing devastation and death, and forming a great lake. There was a cry and a wailing, and, in the Gaelic tongue, these found expression in the words:

| '' Loch-a-Nis !" | "A loch now !'' |

| " Lcch-a-Nis !" | "A loch now !'' |

and this is how the derivation of Loch [ 13] Ness is traditionally accounted for. This legend, while deeply interesting, is only one which is found associated with numerous other place-wells, and is, indeed, supposed to be traceable to one of our world-wide myths. The great probability is that Loch Ness took its name from the association with the district, in early Christian times, of the Irish King, Conchobar Mac Nessa ("Conochara mor ruadh o'n chuan"), who is supposed to have settled there. Within recent times, however, the waters of Loch Ness were believed to contain virtues of no ordinary kind. They never freeze, and the old people used to say that there was a connection between its bed and the volcanoes of Southern Europe. Certain it is that its waters have show n abnormal roughness invariably when any of these burning mountains was disturbed. It was also believed that there was a connection between it and a well at the top of Mealfourvonie, and an ancient legend says that a herd-boy threw his '' glocan '' (a piece of stick with a stone fixed into a split at one end) at a cow near this well, and that the stick, disappearing in the well, was found long afterwards at Bona, near Inverness.

But though our history embraces Loch Ness-side as a whole, a short account of the particular glen which our story especially concerns would seem necessary. This glen - Glenmoriston - lies geographically pretty much north and south between the south-western shore of Loch Ness and Kintail, in Rossshire. It extends to some thirty miles in length. It is confined nearly throughout by hills of considerable altitudes, and the scenery is of unsurpassable magnificence and beauty. There, hill and forest, corry and valley, loch, river, and burn, all unite in lending a completeness of charm to a picture on the production of which Nature would seem [ 14] to have bestowed her most sympathetic attention. It is as if she lingered over the work with a love for its every detail. The hills, while majestic and grand, are yet characteristically pleasing in outline; the forests, while luxuriant, are never monotonous; the corries and valleys have an indescribable freshness about them; and whether in sunlight or in moonlight, seeing Glenmoriston at its best gave us the feeling that we were veritably in a fairy land of dreams, of music, of love, and of joy.

The early history of Glenmoriston is shrouded in practically impenetrable obscurity. The very meaning of the name "Glenmoriston" has been found difficult. The local version of it - and it seems the best - is to the effect that it is directly descriptive, and means what its spelling indicates, namely, "the big glen of the deep falls." Archie Grant, one of its best bards—if not, indeed, the best of them - at page 58 of his published works, and when he would seem to be addressing himself to the subject specially, explains it as " Gleann-mor-easan- domhain," the meaning of which words is both easy and obvious. It has been suggested that the name of Meirchard, the patron Saint of the Glen itself, may have entered into the "Moriston" portion of the word, and " Invermorchen," which we find, at one time, applied to Invermoriston, Urquhart and Glenmoriston. would lend some colour to this theory. But theory the last derivation will, we think, continue to be ; and the popular explanation appeals to us as superior.

It is well into the Christian era before there is any definite or trustworthy reference to the Scottish High lands in history. But if we go upon ethnologic grounds we can read backwards with a considerable measure of [15] probability. It would, however, be quite fruitless to make any serious effort to localise or identify the aboriginal inhabitants of the Scottish Highlands, or of any division or sub-division thereof. When, for instance, Loch Ness-side was first peopled, and by whom, would be a subject exceedingly difficult of satisfactory historic treatment. But quite sufficient for all useful purposes in that connection can be guessed. Prom the legendary and traditional history of the district it can be gathered that the little people who appear to have lived in caves, and to have supplied the prototypic material underlying fairy tales in general, existed there, as elsewhere in Britain and Ireland, and as, more or less, everywhere else at one time the world over. Those probably were the aboriginal people, a sort of mongrel, non-Aryan race, and possibly that known in European race-history as the " Turanian," and there would also have been included, in prehistoric times, a certain Nigritic element. Our next step brings before us the people who, throughout the British Isles, made their way to the more mountainous districts and the fast nesses - and who were among the earliest settlers from the Continent - to save themselves from the later and more civilized incomers, who took possession of the plains and the townships, such as they were. Those were, at anyrate partially, a mixed race, but partaking somewhat more of the dark elements than of the fair or reddish, and probably to a considerable extent long-headed. They would have spoken an early British language, which sub sequently came to be known as Pictish. On these strata were later super-imposed the fairer and redder and more broad-headed race - also a good deal mixed, who spoke a language substantially that of latter day Gaels. It is immaterialwhetherthese are designated " Picts " or [16] " Caledonians ;"along with the Scottic element from Ire land - itself in close relationship with the principal race- constituents already in the country, and which (while preponderating latterly in the south-west and along the western seaboard) had influenced considerably inland - they represented the great Celtic Race. There remains to be added only the percentages of Scandinavian blood, most common in the Western Isles, and - but in very small proportion - of comparatively pure Saxonic and Norrnan blood. Loch Ness-side district and Glenmoriston, as the Highlands generally, shared in the consolidation of all these into two greatly preponderating race-divisions common to Britain and Ireland, and which we have else where described as "Ibero-Celtic" and "Germano- Celtic" respectively. Ample evidence of this admixture has survived in the district under contribution. We have seen within its bounds features and formations which ranged from the early types to the faces and figures of the present day, and prevalent in most parts of the British Isles. The type known as "Caledonian" appears to have at one time been largely represented on Loch Ness-side, and throughout the Glenmore Valley. The settlement of the Grants and their followers - who were a considerably fairish or xanthous people - would probably have slightly affected the district ethnologically. Dr Beddoe, in "A Contribution to Scottish Ethnology, 1853", says: "The Glenmoriston folk, although mostly Grants, and therefore, according to Mr Skene and others, descendants of the Siol Alpine, appeared to me to differ much from most other Highlanders in their broad and burly forms, and fair, smooth, comely countenances." This was applicable, however, to a certain proportion of the population only; the residue included very different elements.

[17] Some time after the commencement of the sixth century we find Scotland divided into two main divisions - Northern Pictland and Southern Pictland, and those engaged in fierce warfare with each other, in which the Scots, who had come into the country from Ireland and gave it its name, were taking an active and most important part. It should, however, be kept in mind that those divisions were much more territorially than racially distinctive. The war was in large measure a civil war, and continued till the Union of the contending powers under Kenneth MacAlpin, about the year 850AD. That event in effect was a victory for the Scottic civilization, politics, and language, all three of which began in course to predominate. Absorption was not, however, immediate. It required some hundreds of years to shatter the Northern independence to any material extent; and Loch Ness-side district, being then included in the great province of Moray, which held out long, we may safely conclude that it would have not been among the first to become subject to the Southern authority. It is practically certain that most Northern districts, and the Isles generally, did not for many centuries wholly and unconditionally give their allegiance to the united interests as represented by the Scottish Crown. Large tracts in the North and West, including the Isles, kept up a sort of guerilla warfare all along;and the rise of the mighty house of Clan Donald, about the year 1150AD , established a great and power ful principality, which, to all intents and purposes, at the time became a separate and independent kingdom. The MacDonalds wielded princely authority over the Isles, most of the Western seaboard, and North as far as Rossshire - if not further - for, at least, the long period [18] of some 350 years, with the exception of a few short intervals ; and we find Glenmoriston and district included in this extensive lordship. The Glen was held of the Lord of the Isles by four or five families of the Mac Donald Clan, as vassals, who survive in local story as "Clann-Iain-Ruaidh", "Clann-Iain-Chaoil", "Clann- Ill-Easbuig", "Clann-Eoghainn-Bhain" and " Clann- Alasdair". As a rule, the chief among these, who would appear latterly to have been " Mac- Iain-Ruaidh," met the Lord of the Isles yearly at Aonach, often when on his way to the North, and exchanged with him tokens of allegiance and fidelity. Interesting legends regarding these MacDonalds will be found recorded elsewhere in this book, under "Coire- Dho," to which the reader is referred. The district was in the possession of the MacDonalds as late as towards the close of the fifteenth century, when it was handed over to the Earl of Huntly. For some time previous, the MacDonalds had been represented locally by members of the family of MacLean of Lochbuy, but of whom there is not much trace in Glenmoriston; and these having given Huntly some trouble, both Glenmoriston and U rquhart were, after an arbitration, let to Rose of Kil- ravock, who soon threw up his tenancy. Huntly then handed these troublesome lands over to Sir Duncan Grant of Freuchy, Chief of Grant, an influential family, having already, through possessions in Stratherrick, a territorial relationship with the Ness Valley. Grant appointed his grandson, John Grant, known as "Am Bard Ruadh " (the Red-haired Bard), to the lands of Urquhart and Glenmoriston. He was the first of the Grants to settle on Loch Ness-side, but he confined his lordship chiefly to Glen-Urquhart.The MacDonalds were still giving [19] trouble in Glenmoriston, and there was much feud and feeling, but during the early years of the sixteenth century the whole district became Grant's own property. The first of the Grants to settle in Glenmoriston was John, the natural son of the Bard, to whom the Glen had been handed over by his father. John appears to have been a man of remarkable personal strength and force. The story of his coming to Glenmoriston is interesting in tradition. The Glen, from various causes, had become, as can well be imagined, practically a waste land, and the inhabitants had come to be known as a wild and comparatively fierce people. John appears to have possessed, as well as strength and force of character, a somewhat wild and indomitable disposition. He is represented as self-willed and turbulent, and his father, knowing the state of Glenmoriston at the time, is said to have made up his mind to send his son there, just to see whether the people of the Glen and he would either '' kill or cure'' each other. But John Mor and the Glenmoriston people, after a while, came to understand each other remarkably well. He exercised great kindness and hospitality towards them, and eventually they took to him with every sentiment of loyalty. The story is told of some of the dwellers in Coire-Dho coming down to the straths for meal, soon after John's arrival in the Glen. They were keeping to the higher ridges with their ponies so as to avoid being seen by John and his party. John, however, intercepted them, but instead of a fight, friendly feelings eventuated between him and them—a friendship which grew from "more unto more" as time passed. John extended his possessions considerably, having obtained charters of Culcabock, Cnoc-an-Tionail (the Hut of health), and the Haugh, near Inverness; also of certain

[20] lands in Strathspey; and, Mr Wm. Mackay says, Urquhart and Glenmoriston in the Western Highlands, which latter the Grants do not appear to have ever taken actual possession of. He was married twice. His first wife was Elizabeth, grand- daughter of Sir Robert Innes of that Ilk, and the story of his second marriage is characteristic. A daughter - or, as some say, a grand-daughter - of the Lord Lovat of the time, returning from the West, where she had been the wife of Allan MacRory, Chief of Clan-Ranald, asked John Mor's protection while passing through the Glen on her way home to Castle Downie. In response he invited her and her retinue to his residence, at Tomintoul, where, in a very short time, they were married. Archie Grant says with reference to this event:

| 'S i oidhch' ann | |

| A' gabhail an rathaid, | |

| 'S bha iad an ath-oidhch' posd'. |

(" One night she was passing by the way, The following night they were married").

It would be wrong to suppose that the MacDonalds gave way easily, however, to the Grant power and influence. On the contrary, tradition points to there having been a stubborn and somewhat prolonged resistance on the part of the older inhabitants. But the Grants had the assista nce of the authority that was vested in their supporters, while the House of MacDonald was no more what it had been. There was, also, to a certain extent, a conflict between two civilisations on a small scale;while there is reason to conclude that there was not too much regard to right in those times, the Grants, assisted by others at least as unscrupulous as themselves, paying as little attention [21] as possible to either justice or fairplay. The following verses convey a suggestion of how these two leading clans in the Glen - the MacDonalds and the Grants - were coming to understand their relationship in the process of amalgamation. A married couple address each other in a bantering sort of manner, apparently good natured, but with a suspicion of a sentiment which betrays a feeling of distant feud. The parents express their opinion of their respective clans to their child, whom one of them is nursing:

| Mo laochan, mo laochan, | |

| Mo laochan, mo ghlaisean. | |

| 'S tu chinneadh do mhathair, | |

| Luchd a' chlamhraidh 's an tachrais. | |

| Bhiodh a' cireadh 'sa' cardadh, | |

| 'N uair bhiodh cach anns na baiteal. |

These sentiments would seem to have been expressed by the father, and the mother replies:

| Tha mo leanabh Chloinn Domhnuill, | |

| Luchd a' bhosd 's nam beul farsuinn. | |

| Gur a car thu dh' Iain Putach | |

| Dha 'm bu duthchas bhi bradach. | |

| Sliochd 'Illeasbuig na blionachd, | |

| Bhiodh a' spionadh nan craicionn. |

But she adds:

| Luchd nan sporanan troma, | |

| Gum bu shomalt' air feachd iad. | |

| Le 'n cuid gunnachan dubh-ghorm | |

| Dheanadh smuid 's a' Charn-Tarsuinn. |

John was succeeded by his son Patrick, from whom came the patronymic "Mac-'ic-Phadruig" - latterly "Mac-Phadruig". It was during his time that the Grants took part in the memorable skirmish at [22] Inver lochy, known popularly as "Blar-Leine" - a bloody engagement between the Frasers of the Aird, assisted by certain neighbouring clans, and the Macdonalds of Clan-Ranald, the result, like so many of the kind, of a family feud. It was in Patrick's time also that Grant of Ballindalloch obtained a Crown Charter of the Grant possessions, which, after a number of years, however, were recovered by Patrick himself. He was married to a daughter of Campbell of Cawdor, who figures as the central character in a pretty romance, the story of which has survived. When Patrick Grant made up his mind to take unto himself a wife, his choice fell on Miss Campbell. Whatever the reason, there would appear to have been some obstacle to the marriage. But "where there's a will there's a way;" and, in the circumstances, Grant, along with a few of the most faithful among his people, adopted a course not quite uncommon at the time: they made a raid on Cawdor, and stole the lady, who, in due course, was married to Grant. Her whereabouts were for a while quite unknown to the Cawdcr family; but eventually they heard where she was, and her father paid her a visit. Grant lived then at Tom-an-t-Sabhaill, Inverwick, it is said, in a very primitive dwelling of wattles and turf ("tigh caoil"). It was then, as the story has it, that Campbell of Cawdor ordered skilled workmen, from Inverness, to build for the Grants a better home, and the portion of the present mansion at Invermoriston known as the "Tower" ("an Tur") still remains of that building of long ago. Cawdor found his daughter much altered;and the old people used to say that certain circumstances turned up which involved her identification by the impression of a, key which had been burnt into the flesh of her thigh as a child.

[23] John, known as "Iain Mor a' Chaisteil" ("Big John of the Castle") from his having made some additions to the family mansion at Invermoriston, succeeded his father. He was also a man of exceptional strength and individuality. It was he who, when at Holyrood Palace on a visit to the King, accepted a challenge from one of those champions who went about in those days, ''spoiling for a fight". But the contest did not go beyond the stage of shaking hands. In that process John squeezed his opponent's sword hand into pulp. He also figures prominently in a story regarding the exhibition of a candlestick and candles - both of an unusually unique type - which will be found elsewhere related, under "Coire-Dho," already referred to. John was married to a daughter of the Laird of Grant. With his period is associated the feuds between the MacDonalds of Glengarry and the Mackenzies, over lands on the West Coast, resulting in deadly quarrels; also the legendary burning of the church of Kilchrist, the skirmish at Lon-na-Pola, near Mealfourvonie, and the memorable escape of Allan of Lundie by swimming Loch Ness at Rusgaich - already all well known narratives, but closely bound up with Glenmoriston history.

John was succeeded by Patrick as fourth Laird. During his time there was much unrest and strife throughout the whole district, caused by various con- tributory circumstances. James Grant of Carron ("Seumas-an-Tuim"), the notorious freebooter, continued for years a source of danger and discord among the Grants, everywhere between Glenmoriston and Strathspey, and raids and reprisals were common. Patrick was married to a daughter of Fraser of Culbokie. John, his eldest son, known as "Iain Donn" ("John the brown-haired"), succeeded Patrick. It was during [24] his lordship - which was also one of .adventure and much commotion - that the property, extending from Loch Ness to Inverwick on the south side of the Moriston river, is understood to have fallen into the hands of the Lovat family, and that Robertson of Inches, near Inver ness, claimed the lands of Glenmoriston and Culcabock, under an arrangement entered into with John's father. It has for long been accepted as history that the Grants at this time burned the barns at Culcabock. But the statement has recently been put forward on good authority that the plundering for which the Glen moriston Grants have so long been blamed was probably the work of Montrose's army, during the siege of Inver ness, in 1646. The Grants having obtained possession of Robertson in Inverness, a settlement was eventually effected, which resulted in Grant giving up Culcabock to Robertson, and Robertson laying no further claim to Glenmoriston. During John Donn's period, Huntly, General Middleton, and General Monk all passed through Glenmoriston, and at least one engagement - between the two former - took place there. It was also the period of the great campaign, of which Montrose and Alister Mac Colla were the leading heroes. John was married to a daughter of Fraser of Struy.

John's successor was his son, John, known by the name of "Iain-a'-Chreagain", from his having a dwelling-house at a place called "An-Creagan-Daraich" ("The Oak Rock"), near Blairie. He was another man of remarkable strength and bravery. He was present at the Battle of Killiecrankie, in 1689, where he and his followers fought side by side with Glengarry and his men, as they generally did in those days. From what tradition has handed down as to the conduct of [25] those warriors in that battle, there is ample evidence that they signalised themselves on the occasion. Alasdair Dubh of Glengarry was considered one of the best swordsmen of his day, and Grant of Glenmoriston appears to have been a good second, while their followers included men of exceptional dash and strength. Among several stories told of Alasdair Dubh, there is one which tells that he and a near relative engaged a room on their way to the fight, which they reserved for the following night if they should return. In the gloaming of that day Alasdair appeared and claimed his room; but the landlady did not recognise him. He was bespattered with blood from head to foot. She asked what had become of his companion, and Alasdair mournfully replied "Alas! my brother is no more." See"Clan Donald," Vol.II,p.452. Another tradition says that Alasdair was once drawn into combat with a Southron champion. He appears to have been somewhat advanced in years at the time, and was not so nimble as in his better days. But, nevertheless, he soon put his opponent to the rout; and making a dash after him and catching him along the back by the point of his claymore, he exclaimed "You Sasunnach dog! if you were two inches nearer me there would be no mercy for you." It was at the Battle of Killie crankie, it is said, that one of the Glenmoriston men distinguished himself by cutting a trooper in two halves by one stroke of his sword, a feat also credited to John Grant himself:

| ' S ann an Cille-Chreagaidh thall | |

| A chuir iad iomadh ceann ri talamh, | |

| Far 'n do sgoilt Iain M6r an trupair, | |

| 'S cha b' e chiurradh bha e 'gearain." |

[26] John Grant was present at the skirmish at Cromdale. and was out in the 1715; and for his part in all these disturbances Invermoriston House suffered burning, and the family were again deprived of their estates for a time. It was in John's period also that the Battle of Glenshiel took place, in which the Spaniards, who had come into the country to fight for the Stewarts, were defeated by General Wightman. John was twice married: (1) to a daughter of Baillie of Dunean, and (2) to a daughter of Sir Ewan Cameron of Lochiel.

"I ain-a'-Chreagain" was succeeded by his eldest son, John, who died soon after his accession; and Patrick his brother, popularly known as "Padruig Buidhe" - from the yellowish colour of his hair - succeeded him.. Patrick was locally known as a remarkable hunter. He was out in the '45, at the head of a strong contingent of his people, and his time will be remembered in Glen- moriston as that in which the effects of that troubled period were felt throughout its entire bounds. Few districts, if any, in Scotland suffered more cruelly from the atrocities and the rapacities of the English Butcher and his demon gang than Glenmoriston. There, man, woman, or child was not spared. Details of the horrors of the time make repulsive reading. They include brutally using a young girl and hanging her to a tree, at Livisie, after subjecting her to cross-questioning as to the whereabouts of the Prince and his men;unspeak able treatment of men, women, and children at Dun dreggan, Inverwick, and elsewhere; the harrying of the Glen from end to end; and the treacherous betrayal of some seventy of its male population, who, after imprisonment in Inverness for some weeks, were sent to London, and eventually shipped off to Barbadoes, whence [27] only some eight or nine returned to their native country; while among numerous ravages destructive to property, Invermoriston House was again burned down. And yet while the English and their followers on the one hand did their best to render the district a veritable inferno, the natives were adding a chapter to history which will be read with unbounded admiration so long as fidelity and bravery continue to be characteristic of true manhood. There, while brute force ravished virtuous women and murdered the defenceless, a few men, whose names will remain illustrious beyond many, despised a great bribe and risked life and everything for the safety of him whom they honoured as their King. The memory is a glorious one, not only for Glenmoriston, but for Scotland and the civilised world. Extended reference to the illustrious and patriotic conduct of these men is elsewhere made in this book; but we must not here overlook to mention the death of Mackenzie, the pack man, who suffered himself to be killed in the Prince's cause, at Ceannacroc, exclaiming with his last breath, as he was being dispatched by the English troopers - ''You have killed your Prince'' - a circumstance which most certainly favoured Charles very materially at the time. Patrick was married to a daughter of John Grant of Crasky, a relative. She is remembered as " A' Bhan- tighearna Ruadh " ("The Red haired Lady").

"Padruig Buidhe" was succeeded by "Padruig Dubh" - a man of great physical powers. It was he who, returning home one night late from Invergarry, found the great iron gate on the river at Fort Augustus locked. Despising any such obstruction, he wrenched the gate from its strong hinges, throwing it into the river, from which it required a few men to haul it out.

[28] He was a man of very social habits, and held kindly intercourse with his people, who admired and loved him. He married a daughter of Grant of Rothiemurchus, who, from having been much marked by the smallpox, was known locally as "A" Bhantighearna Bhreac" ("The Pox-marked Lady"). A very tragic accident happened to a near relative of Patrick, which cast a gloom over all the Grants. Patrick and Alexander Grant, sons of Grant of Portclair, and cousins of the Glenmoriston family, were returning from Fort Augustus on New Year's Eve, 1789, when, finding it difficult to cross a burn much swollen by a great rain- storm, Patrick stumbled and was drowned. Alexander found it beyond him to break the sad news to his father, and he consulted Glenmoriston in his sorrow. Glen- moriston undertook to accompany the young man home, and to acquaint the Portclair family with the details of the accident. Old Portclair was very frail at the time, and it is said that he surmised something not pleasant when he saw his brother at his side. " Surely some evil circumstance has brought you here on New Year's morn ing, so early," he said to Glenmoriston. This misfort une awakened the sympathy of the whole country around, and the following record of it by the local bard, John Grant, the father of Archie Grant (of whom more later on), imparts a feeling of sadness still:

| Air ar culthaobh 'm Portchlar— | |

| Fear an t-sugraidh 's an sta | |

| 'N ciste duinte fo'n fhaid, | |

| } S gu'm bi iomagain gu brath | |

| Air an duthaich is fhearr coir ort. | |

| [29] 'S ann tha 'n sgeula nach binn | |

| 'N diugh ri sheinn .anns an tir— | |

| Mu'n fhear cheutach 'bha grinn, | |

| 'S iad an deigh thoirt a linn'; | |

| 'S truagh a dh' eirich dhomh fhin | |

| Nach fhacas ri m' thim beo thu. | |

| Thug a' Challuinn oirnn sgriob; | |

| 'S olc a dh' fhairuich sinn i; | |

| Thug i 'm fait bharr ar cinn ; | |

| Thainig dosgainn ri linn | |

| Fear do choltais 'thoirt dhi'nn | |

| Ann an aithghearra thim ; | |

| 'S tu air do ghearradh a t'fhior bheo-shlaint'. | |

| Tha a chairdean fo ghruaim, | |

| 'S ann an casmhor tha cruaidh, | |

| O'n chaidh Padruig thoirt bhuath, | |

| 'S nach bu nar e ri luaidh— | |

| Fear do naduir is t-uails' | |

| Bhi ga d' fhagail 's nach gluais ceol thu. | |

| Thuit a' chraobh ud fo bhlath, | |

| 'S cha tig aon te na h-ait' ; | |

| 'N uair a shaoil leinn i 'dh' fhas | |

| 'S ann a chaochail a barr ; | |

| ' S leir a dhruidh sud air each; | |

| 'S soilleir dhuinn gum beil beam' mhor asd'.. | |

| Tha do bhrathair gun sunnd | |

| O'n a chaidh tu 's an uir ; | |

| 'S nach bu gharlaoch gun diu | |

| Bha e 'g airidh ach thu, | |

| Fhir bu tlath sealladh suil; | |

| 'S anns gach aite bha chuis mhor ort. | |

| 'N uair a thionail an sluagh, | |

| Eadar chumand' 's dhaoine uails', | |

| Bha iad uile fo ghruaim, | |

| Mu chul bachlach nan dual. | |

| [30] Bhi dha thasgaidh cho luath. | |

| Ann an clachan 's an uaigh; | |

| Sgeul bu duilich ri luaidh | |

| Aig gach duin' orb a fhuair eolas. | |

| Fir an t-Sratha so thall—- | |

| Thainig iadsa na'n ceann— | |

| Ga'r 'n robh 'n cairdeas clio teann | |

| Bis na dh ; fhag thu 's a' ghleann, | |

| Chuir do bhas orra snaim | |

| 'Nuair a chaidh iad na 'n rang comhla. |

We find the story of this poem attested by a gravestone in Invermoriston Churchyard, which bears the following inscription: "This stone is placed here by Alexander Grant, Portclair, in memory of his brother, Patrick Grant, who departed this life on 31st December, 1789, aged 33 years." Alexander was the father of Patrick Grant, Inverwick, Glenmoriston - whither the family had removed - and one of the strongest men ever heard of in the Glen. He emigrated to America.

John, the eldest son of Patrick, was the next Laird. He joined the army, and passed some time in India. He was married to a daughter of John Grant, Commissary of Ordnance, New York. He died at Invermoriston in the year 1801.

He was succeeded by his son Patrick, who was killed by a fall from a tree while on a visit to Fraser of Foyers, to whose daughter, his own cousin, he was engaged to be married. There is a touching though melancholy story connected with this accident. The young lady is said to have felt the death of her lover so keenly that she fell into a decline;and day after day, while suffering, she made her way down to a point at Loch Ness-side from which she could view Invermoriston House and grounds, [31]

a short distance beyond which the remains of the object of her affection lay cold in the family burying-ground of the Grants. She married, however, but lived only for a few months. After her death, her remains were buried at this spot, beside those of her father and mother, and a monument marks the place—a small plot of ground there being said still to belong to the Glenmoriston Estates.

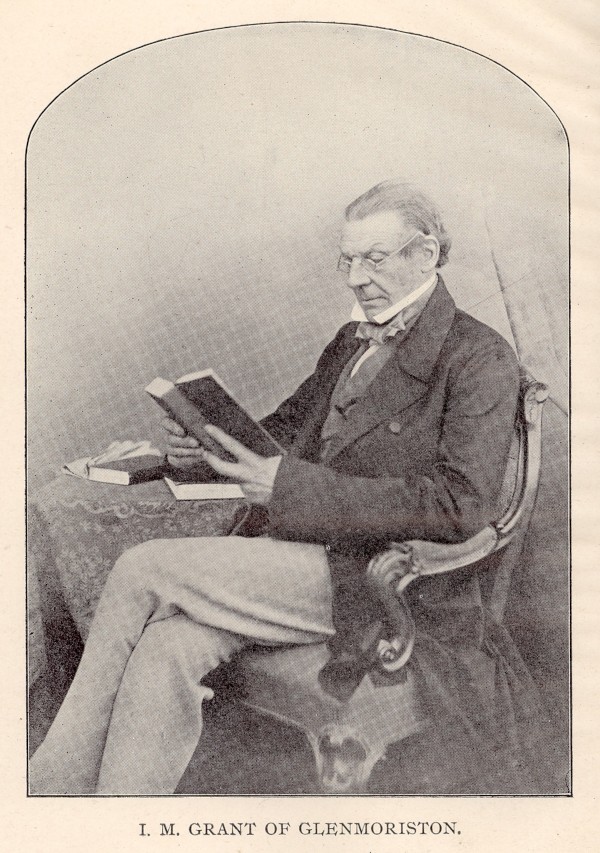

We have now arrived at an important period in the history of Glenmoriston, the accession of James Murray Grant, J.P., D.L., the 12th Laird, who succeeded on the death of his brother. He was one of the most influential and most popular Highland lairds of his day; in all respects an ideal landlord; a friend and a father to his people. In Glenmoriston, and indeed wherever known, he was respected and admired, we might say, not a little adored. He extended the family possessions by important additional acquisitions of land, among which were Moy, Knockie, and Foyers Beg. He was remarkable for his urbanity and homeliness. Readers will find his name mentioned on several occasions throughout our story. He lived with his people on the most friendly terms. Numerous anecdotes are still quite fresh in the district which testify to his extensive popu larity. The people approached him with great freedom, and as if he were an indulgent relative. His employees addressed him without any conventional reserve. Archie Grant, his bard, Finlay MacLeod, his piper, Fraser, his gardener, and all the rest of them, spoke to him as if he was one of themselves. It is related that he asked a tenant on a certain occasion, after the man had done some work for him, whether he preferred a dram to a drink of beer. "If it's all the same to you, Glen, both [ 32] would be best," was the suggestive answer. He is repre sented in another instance as having promised a pair of boots to a certain countryman, and he duly gave the necessary authority to the shoemaker. True to the traditions of his trade, the Crispinite delayed the execu tion of the order to a length of time that exasperated the other party, who .appealed to Glenmoriston. "You will get the boots, my friend," said Glen; "the shoemaker has promised me that." "Och!" said our hero, rather contemptuously, "the shoemaker is as great a liar as yourself, MacPhadruig!!" He went about in so simple and homely a way that he frequently enjoyed good fun from strangers who did not recognise him. He was one day moving about Alltsaigh, when a man appealed to him to help him to place a bag of meal on his horse's back. MacPhadruig was a man of great strength, and his assistance in the matter counted very materially. " My word! you are strong, my gray shepherd lad," was the crofter's exclamation.

MacPhadruig was married to a daughter of Cameron of Glen-Nevis, by whom he had a large family. He died at Inverness in 1868, his eldest son, John, having pre- deceased him by about a year. In these circumstances, Iain Robert James Murray Grant, the eldest son of John, and who was born in 1860, succeeded, in 1868, as fourteenth Laird. He is a worthy successor to his illustrious ancestors. He is of the best type of a High land landlord; is a father and a friend to his people; and enjoys a sacred and secure place in their affections.

Thus the Grants have possessed Glenmoriston, with short intervals in which feuds and disturbances, so common in the olden time, brought about occasional short breaks, for the long time of over 400 years. Glenmoriston and [33] district have undergone, in common with the whole country, very great changes during these four centuries. Time has been there, as elsewhere, exercising its prerogati ve as the great magician, and has created quite a new world out of the old.

Some of the principal family occupants of the Glen during, roughly, most of the 18th and the first half of the 19th centuries may be mentioned. Commencing with Corry-Dho, with which interesting place is associated the story of the three brothers, of Cloinn 'Ic-Alasdair, who wished to be buried in Clachan Meirchard with their faces towards their beloved Corry (given at length else where in this book), there was resident there, among others, Black John of Corusky and his family, said to have been Frasers. At Beul-ath-Dho, on the north side of the river Moriston, and .about half-way between Tomchrasky and the river Do, lived Lewis Grant, known as "Ludhais Bheul-ath-Dho". One of the last residenters in the Corry was Alexander MacDonald, the father of Messrs A. & D. MacDonald, and of the late Mr Ewen MacDonald, all well known in Inverness district as successful agriculturists and fleshers. MacDonald spent his last years happily at Inverness, but always retained fond memories of the Corry and its associations. He was an excellent seanachie, and a man of exceptional intelligence and virtues. A number of small tenants occu pied Tomachrasky, among them one John MacDonald, known as "Iain Mad Alasdair." Crasky had been in the hands of direct descendants of MacPhadruig for a long period of time. Patrick Grant, of Craskie, was one of the famous Seven Men of Glenmoriston, and he was succeeded by several descendants all styled " of Craskie," or "of Craskie and Coineachan."These Grants were [ 34] descended from John Grant III of Glenmoriston - " Iain Mor a' Chaisteil'' - while closely related were the Grant families who held Duldreggan for generations, and one of the last of whom was Alexander Grant, factor for Glenmoriston, circa 1800-1850. At Crasky latterly were William MacDonald, and John and Alexander Grant, called "MacRaoghail" (" Son of Ranald"). These Grants - father and sons - were originally of the Glen moriston family, and were remarkable for their bodily strength. Aonach was in the hands of Captain Mac-Donell, and a family of MacDonalds, one of whom occupied the inn. Patrick Grant, one of the Grants of Portclair, was at Inverwick. Thereafter Ewen Cameron (" Eoghann Buidhe"), Ewen MacDonald and Patrick MacDonald ("Mhic-Alasdair," "Mhic- Aonghuis"), took possession of Tomachrasky, and of all the land from the old march between Crasky and Tomachrasky, on to the Eilrig and Bealach-an-Amuinn, the boundaries of the Glen moriston estate. These three men married three sisters, daughters of Ewen MacDonald of Libhisie ("Eoghann MacDhomhnuill"). Ewen MacDonald, the bard, was in Dalcattaig, and, for a time afterwards, Mackay, of Sheuglie, GlenUrquhart, married to a daughter of Major Alpin, and their family; and small tenantry dwelt in Invermoriston, including the hamlet of Achnanconeran.

Chapter 1 |