"Story and Song from Loch Ness-Side" |

| By Alexander Macdonald |

| Chapter XII |

| Of Halloween, Kent-Day, Sports, and Pastimes, &c |

[184]

Hallowe'en was generally observed in ancient times as the eve of All Hallows' or All Saints' Day, which is the 1st of November. All Hallow's Day, or Hallowmas, a festival of the Roman Church, is understood to have been instituted by Pope Gregory IV, about the year 835, in honour of the saints to whom separate dates are not set apart in the calendar. This festival was fixed for 1st November, as on that date is believed to have been held one of the four festival observances of the Northern Pagans. Among the Gaelic-speaking nations the night of 31st October is known, however, by the name of "Oidhche Shamhna 'n uair theirear na gamhna ri na laoigh," which would suggest an independent origin. The derivation is from the word "Samhainn", a term applied in the division of the Celtic year. It is now generally accepted that, at any rate prior to the Christian era, the people, or peoples, inhabiting Celt- land reckoned only two seasons in their year, those being Summer and Winter, and one very ancient Gaelic quota tion divides the year as from Beltane to Samain, and from Samain to Beltane. The root of the word "samain" is explained in a variety of ways, and we were struck with Dr Stokes' interpretation of it, as quoted by the late Dr Macbain, of Inverness, in his dictionary, where it is referred to as meaning "assembly," and as such possibly pointing to the [185] "gathering at Tara on 1st November," which may have been one of the four great Pagan festivals referred to as falling on that date. All things considered, it is most probable that the origin of Hallowe'en may be traceable to the observance of certain rites and ceremonies dating back to a period long anterior to the beginning of modern history, and afterwards assimilated to certain festivals of the Church. The fact of there being so much of the practice of mysticism associated with it would seem to suggest that its customs are but a trans ference of the divination by words, verses, lots, water, figures, &c, so common among the ancients, and of which there is much in Greek and Roman mythology. The fashion for prying into futurity, says Burns, "makes a striking part of the history of human nature". It is but the force of the spirit within trying to reach- beyond its material bounds.

Hallowe'en, the eve of All Saints' Day, appears to have been characterised, more or less all over Europe since very early times, by the observance of popular customs, such as the ringing of bells, the kindling of fires, and various such proceedings. During the Middle Ages the belief was prevalent that invisible spirits roamed about on that night. On Walpurgis Night, on the Continent customs and rites were in vogue, which substantially coincide with those peculiar to Hallowe'en in our own country since. In latter days it had become very common - and the practices have not yet wholly disappeared in the rural districts of both Britain and Ireland, coming now to our own country - to celebrate its return by various, customs partaking of both pastime and superstition.

Perhaps the best popular account of Hallowe'en, as observed in Scotland, is the poem on the subject by [186] Burns. Interesting references to it occur also in "Pennant's Tours in Scotland, and Appendix," and in the "Statistical Account of Scotland";but there is no necessity for quoting from these authorities here. We should rather confine our description to the more important observances distinguishing Hallowe'en which came under our own notice.

As a young man we knew a very social and warm hearted community who looked forward with gleeful anticipations to the coming of Hallowe'en. With its approach a spirit of light-heartedness seemed to take possession of young and old. The world sat easily on their shoulders. As a rule, when the interesting eve came round, the heavy work of the year had been pretty much completed. Food and shelter for man and beast had been provided against the gloomy winter - now on its dismal chariots approaching fast - and fuel was not far away. All felt "cantie and crouse". For the simple needs of life there was a sufficiency, and a little to spare; and neither did cankersome care nor intoxicat ing ambition dull the souls that God had given.

One of the most interesting of their Hallowe'en functions was the "Crannachan" party. The proceed ings were pleasant in the extreme, and delightfully simple. There was no worrying over any such tom foolery as dressing specially for the occasion. Tweeds, moleskins, winceys, all sorts of checks and tartans were in evidence, and in place of hollow-hearted convention ality and etiquette, there was a kindly fellow-feeling one for another all round. The Crannachan con sisted of cream frothed up with a whisk ("lonaid"). Usually a ring or small coin was put into the basin con taining the preparation, and the person finding it in his [187] or her spoon would be the first to get married, according to popular belief.

The practice of divination with the three dishes was regularly in evidence. These were usually plates, two of which contained clean and foul water respectively, the third being empty. They were arranged on a table or dresser, and if a person blindfold chanced to dip his or her hand in the clean water, it meant blissful and innocent marriage; if in the foul water, it indicated marriage with a widow or widower; and if in the empty plate, dreary bachelorhood or spinsterhood was to follow.

Burning the nuts was a favourite custom. The nuts were thrown into a red-hot fire in twos, representing reputed lovers; and if both flamed softly and brightly, it was divined that the sweethearting parties were to come together. If, on the other hand, one or both "jumped out o'er the chimlie", such a consummation as union was not to be looked for. Nut-burning is an ancient and somewhat general practice. In Ireland, when young ladies felt curious as to the faithfulness of their lovers, they placed three nuts - and it is not without interest to observe that the number three is closely associated with Hallowe'en - on the bars of the grate, each nut being named after a lover, who was to prove faithful or otherwise according as the nuts blazed, or crackled, or jumped off. Nut-burning on Hallowe'en appears also to have been - at any rate not very long ago - popular in England, and we find the poet Gay referring to it as follows:

"Two hazel nuts I throw into the flame,

And to each nut I give a sweetheart's name;

This with the loudest bounce me sore amazed,

That in a flame of brightest colour blazed;

As blazed the nut, so may thy passion grow;

For 'twas thy nut that did so brightly glow."

[188] Pulling stalks of corn from the stack was occasionally resorted to. A party of lads and lasses went hand in hand round a stack, each pulling three stalks at random. The straighter and longer the stalk, the better looking the husband or wife; while the absence or presence of grain on it denoted poverty or comfort in the matri monial state. This custom would seem to be a variant of one previously common, and known as "fathoming the stack."' The party was, unnoticed, to walk three times round the stack, and, on the last round, would meet the apparition of the future husband or wife. In one instance of ghost-seeing we heard of, it is related that a man met, instead of his sweetheart's image, his own; and the story tells that he died soon after.

Pulling cabbages blindfold was also a common prac tice, the size and form of the plant indicating the figure of the future partner. When ground stuck to the stock a dowry was to be looked for. The cabbages were after wards placed above the door, and the name of the person first entering the house was to be that of the future husband or wife.

Winding the clue, though at one time common in the district, has of late years practically died out. The procedure was as follows: All alone, a person went into the kiln, and threw a clue of yarn into the pot ; then winding the yarn to a new clue, towards the end of the process something would be felt to hold the thread. The party then asked, "Who holds?" and the answer gave the name of the future companion in the married state.

In our experience, young women have shown much interest in Hallowe'en divination. They had an especial favour, among other things, for eating an apple [189] before a mirror, combing their hair at the same time, in the belief that the face of the future husband would appear in the glass, peeping over the shoulder. Sometimes the face that appeared was that of a very sub stantial apparition.

Somewhat similar was the practice of wetting the sleeve of a night-dress - or bedgown as was then said - and placing it before a fire, in the belief that, if one lay awake till midnight, the ghost of the future life-partner would steal into the room and turn the sleeve.

Another superstition was that if one ate a salt herring practically raw, when going to bed, by way of causing unusual thirst, the future husband or wife would appear during the night at the bed-side, in a dream, offering a drink of water.

Possibly the most uncommon form of divination was that of going to a burn, over which the dead and the living had passed, and taking therefrom a mouthful of water; thereafter going to a house near by, and listening between the doors, or at one of the windows, for the first name spoken; and this was to be the name of the man or woman, as the case might be, to share with the person her or his lot.

Ducking for apples was a childish custom that had nothing of the mysterious about it, and boys had some disagreeable experiences of it in the nature of a surprise wash, from the temptation offered in that direction to those looking on.

There were some two or three in the community who were known to have more than once on Hallowe'en divined successfully by reading from cups, and eggs, and by a species of crystal-gazing; also by reading from the shoulder blades of animals - "slinneanachd". But [190] these arts were not usually resorted to, and had become quite rare in latter days.

Hallowe'en was frequently taken advantage of for the exercise of a spirit of mischief by the boys. Longstanding scores with cantankerous old men and maidens were settled, but if any "puir body" had shown kindness during the year, the reward, in the shape of turnips, or something similar - frequently at the expense of the disliked - was certain on that night to be tendered.

All these customs and practices are now, however, fast becoming things of the vanishing past;and it would seem as if it were never again to be as at one time it so generally was:

| " Oidhche Shamhna, tus a' Gheamhraidh, | |

| 'S a' bhail' ud thall bha ceol .againn." |

A very interesting institution in our district was Rent-day - a sort of term-day - in which centred much of the countryman's work, whether as farmer, crofter, cottar, artisan, tradesman, or merchant. Rent-day now, however, is anywhere, we think, but a mere apology for what at one time it was in the Highlands, it having, in the procesis of modernising, lost most of the customs and characteristics which clustered around it in the days of old. Then the collection of the rents was frequently in our district inn, and few of our men, of any standing whatever, failed to appear. Early in the morning the usually quiet hostel became the scene of considerable bustle. Some who had not been there since the previous Rent-day were present. In more recent times, most of those old men wore a kind of Tam-o'- Shanter on their heads, and, over suits of home made cloth, a plaid, rolled loosely round their shoulders, and usually carried large hazel sticks. Thus [191] groomed, they sauntered about, seemingly anxious to have their business over. They were really fine speci mens of the human race, well-formed and well- developed, and they greeted each other with the most affectionate warmth.

The order of business at a rent collection for most gave priority to the great transaction of paying the rent, which was felt to be the back-bone of the day's proceedings.

During at any rate most of the period we are dealing with the laird usually attended the rent collections in person. The tenants paid him as well as they could, and willingly;at the same time they looked up to their land lord, not as a commercial autocrat, but as a father and adviser. There were on both sides feelings of mutual interest and reciprocal respect. If the amount was not forthcoming - or only forthcoming in part - the conse quences were not serious. The good laird handed his tenant the customary glass, all the same, as he presided at the table. The local bard makes an interesting reference in this connection: On a certain occasion, when the rents were being collected at Torgoil, Glenmoriston, he, as was his wont, came the way;not that he had any thing very important to attend to, but, as he says:

| "A chionn 'sgu 'm faighinn fhaotuinn | |

| Seasamh an taobh an rum ac'— | |

| 'S toil le triubhais bhi measg aodaich— | |

| 'S cha 'n e gaol na druthaig; | |

| Ach dibhearsan agus sgialachd, | |

| Bho 'n is miannach learn e; | |

| 'S dheanainn coir dhe 'n lach a dhioladh, | |

| Gar a,fiachainn sugh dhi." |

But finding that his adored landlord and indulgent patron, MacPhadruig, had gone home to Invermoriston, [192] our bard simply exchanged a few words with the factor, who does not seem to have proved attractive to him on this occasion, though they were always known to be the best of friends, and he left the company, expressing his feelings in these lines, somewhat disappointingly:

"Ni mi cleas amadan Mhic Leoid— |

|

| Cha teid mi gu mod gu brath, | |

| Gun MacPhadruig a bhi romham, | |

| Cha b' e ceann mo ghnothach each." |

There is some reason to conclude that the Highland lairds left too much power in the hands of their factors. While these officials cannot be held responsible for one- tenth of all that has been laid to their charge, yet the institution which, little by little, grew with the office, did not help, perhaps, to bring about the happiest results. Factors, in many circumstances, had very difficult duties to perform, and, with some exceptions, of course, performed these with comparatively sound judgment and good tact. But the landlords should have supplemented the labours of the factorial office by more of their own personal supervision.

Rent-Day brought together certain types of indi viduality whom to see was never to forget. They were interesting in a high degree - every one of them an original in his way. There was, for instance, the shoe maker of the olden time. He seemed the busiest man in the world. Who knew how many pairs of boots and shoes, ordered possibly at the previous rent gathering, he had not delivered! But he had excuses - and plausible ones - for all. He had not been well for long; or his assistant could not be kept at work: or he had [193] completely forgotten all about the orders; or he had unfortunately mislaid the measures. But each customer would get his order executed, sure enough, within the next week or two - even those whose measures he had mislaid!

Next came the carpenter. He had had a busy and comparatively successful day. He had settled with the factor for certain work he had done for the estate, and with others for sundry jobs that had come to him during the year, such as wheels, carts, barrows, harrows, and perhaps a coffin or two.

Meanwhile the blacksmith had been engaged with his own affairs. But he had not had so good a year as had often been his experience. The season had been a slack one; there had been no wood-work; and all the horses seemed to have required no shoeing.

A very important personage was the country mer chant. He had, as a rule, a good deal of money lying out, and made a great effort on this occasion to realise a, substantial amount. He had a smile for everyone he met.

There were very few among the leading men attend ing the rent collection who seemed of greater import ance than the tailor. Somewhat like the Knight of the Awl, the Knight of the Thimble required a great number of ingenious excuses to cover the multitude of iris unfulfilled promises. He had had a sore finger for a long time; or the addition to the family in the interval had completely upset his house; but all work would be attended to in immediate course, without fail. Still, webs of cloth might lie in his hands, in some cases, from year's end to yearns end.

[194] We must not forget the day labourer, who attended for pay, in many cases, that he had worked for months previous; for it has always been one of the disadvant ages of work in the country that pay-day came round at very long intervals - an arrangement which caused much inconvenience and not a little injustice to many.

Rent-Day sometimes, however, brought about inci dents of a pathetic nature. One occurs to us now. A possibility for some time dreaded began to cast its dark shadow over a happy household. Dear old "Druimag", the faithful and much-beloved dun- brown cow, for some twenty years almost a member of a certain family, was to be sold. During all that time, and the period of greatest activity in the creation of home ties, Druimag had been a most outstanding figure in the economy of that family. She calved regularly every year about the middle of spring, and milked bountifully - milk that was meat and drink fit for a king. She knew the "auld hoose", and every individual that dwelt in it. It was pretty to see her come home in the gloaming to her own door, and pleasant to hear her soft low there, as if announcing her arrival. To the mother's question - "An tu tha sud, a Dhruimag?" ("Is that you, Druimag?"), her low, sweet "moo" was almost human. Then she usually was treated to a drink, or a bit of oatcake, and was driven into the byre to be milked, for the last time that day. She had a preference for the mother milking her, and to an utter stranger not a drop would she part with. And she seemed to love the soft music of the milking song, which the one she liked so well about her so inimitably crooned. Altogether, quite a world of associations had grown about this good old cow, and she- was the object of much warm interest and affection.

[195] But Druimag had grown old, and had to go. The inexorable law of nature had doomed her, and she was no longer considered fit to take her place in the family working. It was decided that she should be sold for whatever she would fetch. It was an infinitely great source of relief that she was not to be killed and eaten by the family - as was sometimes done in similar circum stances - but the idea of having to part with her at all was simply pang and pain to every one. Yet such was the uncomfortable event which a few days would bring- about; and we are satisfied that it was an utterly un welcome one. It fell to the lot of two members of the family to deliver Druimag at her future home. It would not be much more painful for them to be banished to Siberia, or to be burying one of those nearest and dearest to them. It was on a cold, raw winter morning that they loosed her from the "nasg" which so kindly held her at night for so long, to drive her away forever from a home she certainly had learned to love. The father had left earlier it was thought, to be out of the way : the mother had got suddenly very ill; and there was altogether a dreadfully doleful feeling all round. Tears were there; it was unutterable misery

"There was a canker at the heart,

A canker deep and sore."

The journey was a sad one. Every step brought the dreaded snap nearer. Reason occasionally asserted itself, and made attempts to show the practical wisdom of the transaction. But reason was immediately dethroned by an avalanche of memories, which swept all mundane considerations before it unto death. At length the end of the journey was reached. How the buyer - the commercial agent - was envied! He took

[196]

possession, paid the price, and the whole thing was over in its business aspect. But not so in every respect. Two heavier hearts never beat than those that were stung - and stung sorely - by that snapping of a dear old tie - simple in a thousand ways, but yet alive with fond associations and hallowed by genuine affections.

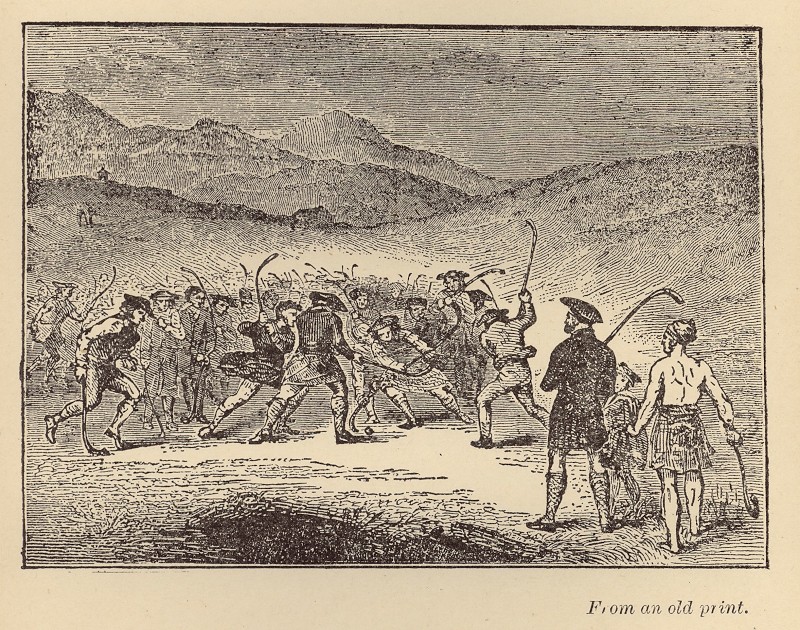

[Illustration] The sports peculiar to the district were not very numerous, but the people always took a keen and lively interest in such as were popular. Among those shinty held the highest place. The game has been known on Loch Ness-side since immemorial times, and enjoyed much partiality during at least the greater part of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, if not longer. On Christmas Day, and again on New-Year's Day, it was quite an institution. In Glenmoriston the laird [197] and his sons, as well as all the leading men, not only patronised the play, but also took a personal part in it. On one of those days the match was arranged for the Upper Glen, usually at Culnancarn, and on the other at Invermoriston, for most on the big park overlooked by the mansion-house. The opposing teams were the men of the one end of the Glen against those of the other, the parties being captained respectively by the laird and a member of his family or a relative. The contest was often keen; but the men were strong. It may not be uninteresting to mention that the father of the writer remembered as many as nineteen young men - all stal wart, healthy, and powerful, and most of them over six feet in height - from the three or four houses in Tom- chrasky alone, present at more than one of those matches; and there were several similar instances. Shinty suited the season of the year when school was best attended. In summer, till some fifty years back or so, school received generally little attention in the district, the children having to help at the home work, which included many duties boys and girls could easily perform. Shinty was a favourite Sunday afternoon pastime in the district at one time.

There was often great sport on the ice in winter. Beautiful slides were at disposal, and many a happy hour was passed enjoying the healthy and vigorous recreation they provided. Frequently on a fine, clear, moonlight night, the sky of deep blue above, shot with countless stars, and the earth around as if carpeted with polished silver, all the young and many of the elderly turned out on the ice. "An Speile" was our Gaelic word for the slide. While some were artistes on the ice, others performed such grotesque antics, in saving themselves from serious accidents, as furnished great [198] amusement to the more expert. A somewhat dangerous practice on the ice was when a number boarded a long form - "furma" - and let it go at full-speed down an incline, after the fashion of toboganning. There was a look-out man and a steersman, but, after all, when the "ship", arrived at her destination - which usually was a ditch or hillock - there was often certain grief. By the force of the contact the "passengers" were thrown straight into space, with the result that some heads met with severe treatment.

After the New-Year festivities had passed, one of the first days looked forward to was Didomhnaich Caisg (Easter Sunday), popularly called "Latha Ghuil- eagan". On this Sunday it was customary to have, in a small way, a feast of eggs. The young folk usually lighted a fire outside, and cooking the eggs there, ate them with oatcake bannocks. A favourite child, such as the youngest, or one petted by parents or kind relatives, was presented with a bannock impressed with thimble marks, or some such design of affectionate distinction.

The word "Guileagan," in some districts "Cuileagan,'' seems to be very old, and is supposed to mean a sacred feast. The custom we have just described, however, was at one time very general in the Highlands. It is obviously on all fours with the egg-rolling common to many countries, and which is found associated with the period of the year known as Easter. We find an inter esting reference to the institution in Dr Carmichael's "Carmina Gadelica," under "Ora Boisilidh":

| " Air a' chuid an uidhean dhuit, | |

| Uidhean buidhe Chaisg; | |

| Air a' chuid an Chuileagan, | |

| M' ulaidh agus m' aigh." |

[199] Some two months after, the Fort Augustus market came round - an annual fair held on the Monday before the second Wednesday of June. With a few silver pieces, earned possibly by odd turns at herding, or a dozen or two of eggs paid for by hundreds of messages during the previous three or four months, a few of the young people travelled to a stance about a mile beyond Fort Augustus to attend the fair. Here they met friends and relatives from the surrounding districts, and spent their little cash on sweets, toys, cheap pictures, and the various trinkets obtainable at such gatherings. Sometimes older people attended. Travelling hawkers and show people were in evidence, and the ballads sung and sold on the occasion supplied the young with singing material for months subse quently. Horses and cattle were marketed and exchanged at the fair. The well-known dealer, Cameron of Coirechoille, patronised it from time to time when in its better days. Cameron was a conspicu ous man in the Highlands. At one time he was the largest holder of live stock in the country, probably in Scotland, owning about 50,000 sheep. Shortly before his death he stated that he had attended the three yearly Falkirk trysts, and the two Doune fairs, for fifty- five years without missing one. Latterly Mr Cameron had given up many of his farms, but he purchased a small estate in Stirlingshire, and one in Skye. Cameron had the reputation of being a kind and considerate friend of dealers and crofters, and was very hospitable to friends. We remember an old man telling that Cameron rewarded him when a boy handsomely on an occasion when he returned a pocket-book containing a. large sum of money, which the other had lost.

[200] [Illustration] Putting the stone, throwing the hammer, and tossing the caber, jumping, and running, were, of course, a good deal in evidence during the summer evenings. These exercises were not, however, entered into with the definite intention of learning the art or system of them, but more by way of passing spare time in a manner congenial to the physical vigour of country youths. Thus the district has not produced trained athletes of [201] note, though there have always been within its bounds quite a number of young men possessing all the necess ary physical strength. On the Stratherrick side there was one - Donald Fraser ("Domhull Mor Chillfhinn") - who sometimes contested honours with the Macdonalds of Creanachan, Lochaber, who were the first of High land athletes of distinction. These Macdonalds, of whom there were four or five brothers, were men of immense bodily strength, and more than one of them exhibited successfully for years as leading athletes, when athletic sports were in their infancy in Scotland.

"Cluich Pheilisteirean" - a kind of quoits-throwing: - was also a favourite summer pastime. The "Peilisteir" was a disc of stone, which was pitched in quoit fashion at a mark placed in the ground some- distance away from the player, and the game was to get the disc nearest to this mark. Four players usually played together - two a-side.

The children's games were, upon the whole, on a limited scale, but were interesting. Little mites passed a lot of time playing at "housies" ("tighean-beaga"). They imagined themselves in possession of dwellings by the mere building up of a few stones, more or less in the form of a square, in which they placed tiny bits of broken dishes and small pebbles by way of furniture. Arranging and re-arranging these amused them, and took the place of toys, which were not always supplied too liberally. For little girls dolls have for long been in evidence.

Older children very much enjoyed a game known as "Ulach fhalach fhead" - a play somewhat similar to "Hide and Seek." "Cluich Sgiobag" was also indulged in. This game consisted of any number of boys and girls, from two upwards, giving each other [202] slight slaps in play, and running away thereafter, as if to evade pretended punishment. Sometimes this play, begun in fun, ended in undesirable earnest, hence the proverb, "Feuch nach tig na sgiobagan gu bhi trom" ("See that the light slaps may not become heavy''). Latterly South-country games, such as cricket in a rough way, marbles, round-and-round, and others, made their appearance in the district. School sports at one time included cock-fighting, but latterly only shinty, quoits, sliding, running, jumping, marbles, and cricket were in vogue.

There is still evidence that Beltane Day had been at cne time observed in our country much in the manner for long common to Scotland. But practically all reference to those customs died out long ago, except to the extent that the poets, almost one and all, have given Beltane prominence as the coming of summer. The couplet:

| " 'N uair thig a' Bhealltuinn | |

| 'S an Samhradh lusanach," |

indicates admirably the common sentiment which sur vived as attaching to Beltane. When Beltane came round, summer, in all its warmth and brightness, was hopefully looked for. The sentiment found expression for itself also in such as the following:

| " 'N uair thig latha buidhe Bealltuinn | |

| Cuiridh 'm fitheach a mach a theanga." | |

| " Air latha buidhe Bealltuinn | |

| Bheir an luchag dhachaidh cual chonnaidh." |

Draughts and card-playing were in evidence latterly, but these games never got a strong footing in the dis trict. Card-playing got into disfavour through the common belief that cards were "the devil's picture books", and that his Satanic Majesty presided whenever

[203]

they were in hand. It was always felt that this pastime gave rise to much wrangling, and many people looked upon it with dislike. There was a terrifying tale that militated powerfully against cards. They were being played one long winter night in a certain house, and as the game proceeded great squabbling prevailed. High words followed, and the name of the devil was on everybody's lips. After the visitors had dispersed, the inmates of the house retired in ordinary course to rest. But there was for them no rest that night. Scarcely were they in bed when the clanking of chains all over the house well-nigh drove them out of their wits; and they could not speak, for they all felt pressed down by an unnatural weight of some kind. The two dogs in the house howled and barked madly, and in their efforts to get into the bed rooms, gnawed away a considerable portion of the fir slabs which partitioned those rooms from the passage. The marks by the dogs' teeth were visible for many years after. When the cock crowed the disturbance ceased;but fear and trembling reigned in the house and in the neighbourhood for many a long day.

There were numerous dark tales which such as the foregoing called up, and of which the well-known story of the loss in Gaick forest, in Badenoch, at the beginning of last century, may be referred to in passing as typical. The tragic death of Macpherson of Baile-Chrodhain ("An t-Oithichear Dubh"), and his party, under what were no doubt the most natural possible circumstances, was construed in popular belief as the work of supernatural agency, and the narrative, for many long years, was never told at a Highland fireside except with mingled feelings of terror and awe. The bards took up the subject, and their

[204]

imagination lent additional fury to the flame. A long composition in "Turner's Collection" (1813), said to be by Duncan Gow, a Badenoch bard of the time, depicts the scene in glowing language:

| An Nollaig mu dheireadh dhe 'n chiad, | |

| Chuir sinn i 'n cunntas nam mios; | |

| Gu ma h-anamoch thig i ris, | |

| Bu ghriomach a' bhean-tigh i. | |

| Cha d' fhag i subhaltach sinn; | |

| Cha d ; fhuair i beannachd 'san tir; | |

| Cha d ; thainig sonas r'a linn, | |

| Ach mi-thoil-inntinn 'san-shocair. | |

| Sheid a' ghaoth am frith nam fiadh, | |

| Nach cualas a leithid riamh; | |

| Chuir i breitheanas an gniomh, | |

| A bha gun chiall gun fhathamas. | |

| Dalladh a,' bhreitheanais chruaidh, | |

| Mhurt e fhein 'e na bh ; ann a shluagh; | |

Bha Prionns' an adhair mu 'n cuairt, |

|

| ' S gu 'n d' fhuair e buaidh an latha sin. | |

| Ach bruidhnidh 'n linn a thig an aird, | |

| Am mile bliadhna so slan, | |

| Air a' bhreitheanas so bh' ann, | |

| 'S an sgrios a bh' ann 's a' chathadh ud. | |

| Gadhaig dhubh nam feadan fiar, | |

| Nach robh ach na striopach riamh— | |

| Na bana-bhuidsich ga 'n toirt 's an lion, | |

| Gach fear leis 'm bu mhiannach laighe leatha. |

There is at least another poem on the subject in the language. Frequently repeated also were the stories of the Assynt murder by Macleod, and the Black-Isle murder by John Adams, which made deep, disagreeable impressions on youthful minds when related in circum stances which imparted to them the necessary weird- ness and imagery.

Chapter 12 |